Revisiting the Bancor

A New Digital Universal Settlements Denominator (dUSD) for the 21st Century?

This is the third essay in a series that addresses issues related to global trade dynamics and institutions. The first two essays analysed firstly the implications of Trump’s threatened 100% tariffs on BRICS economies, and secondly the issues of the putative role of US capital markets in financing global trade.

This essay looks at alternative payment institutions, particularly those being developed under the BRICS Clear rubric. The aim is to lay out some historic context by way of revisiting Keynes’ Bancor proposal from the early 1940s, before fleshing out some of the issues that are implied in the development of a BRICS Clear settlements system. In doing so, I do not present a blueprint, but merely aim to highlight the issues that are likely to be those that exercise the minds of those involved in designing such systems and to show that the issues are not irresolvable.

As a reminder:

In the first essay, I discussed the adjustment dynamics and issues, arguing that BRICS nations are likely to be able to effect a full adjustment to the loss of the US market within 4 years at the longest. Different countries will adjust quicker than others. Fiscal policy initiatives and improved multilateral trade coordination could also shorten the adjustment period.

The second essay dealt with a common argument about how American capital markets are necessary to finance the deficit. The implication is that the adjustment discussed in the first essay would be constrained because BRICS nations’ capital markets don’t have the depth that the US capital markets do. This argument is mistaken. The US deficit is not financed by the capital markets; the capital markets are the effect of the financing of its trade deficits via endogenous money creation.

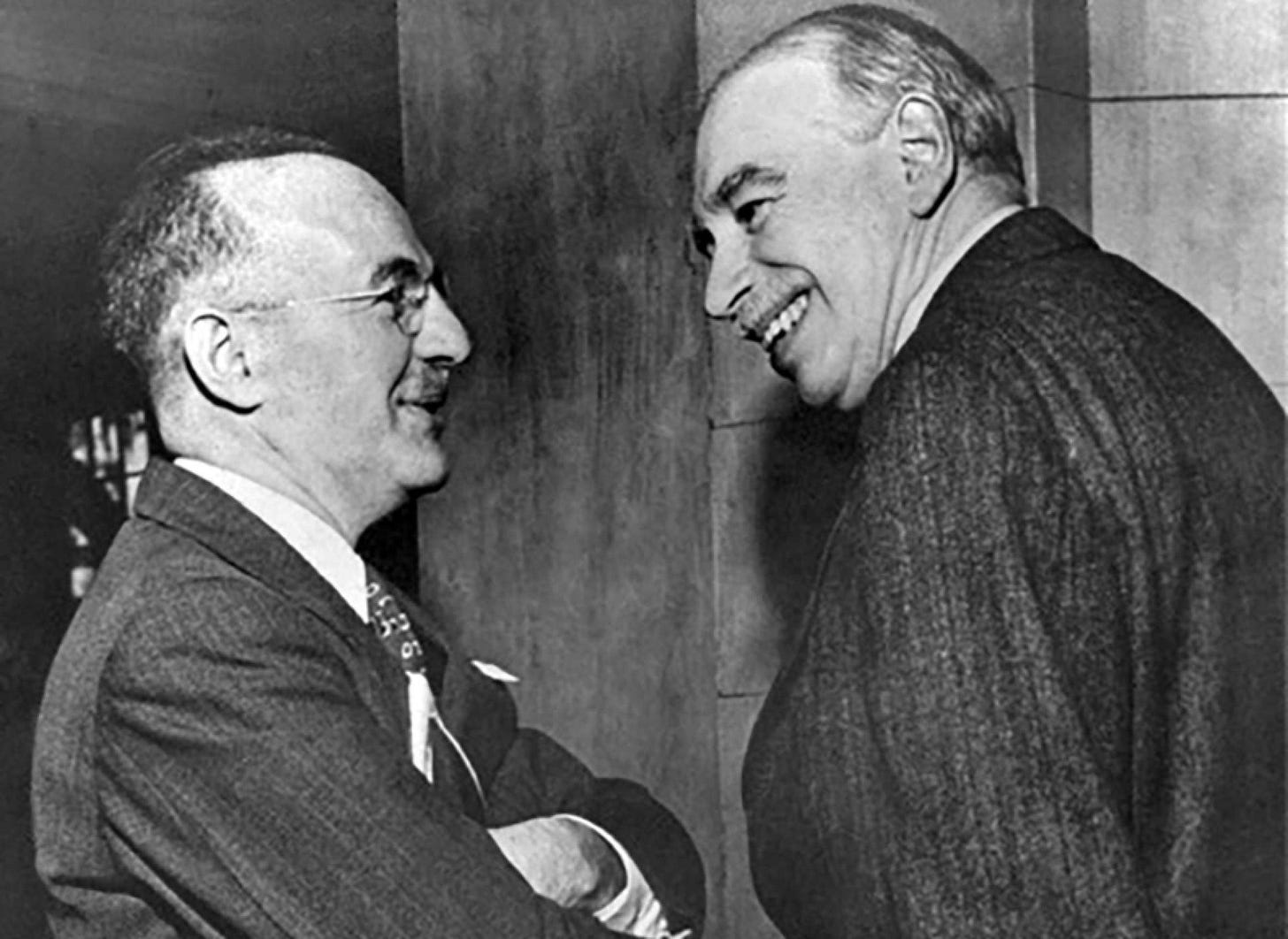

John Maynard Keynes' proposal for an International Clearing Union (ICU) and the Bancor (an international non-national central bank settlements or reserve currency) emerged during the negotiations that led to the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944. His ideas sought to create a balanced global financial system that would promote international trade and prevent economic instability caused by imbalances in trade and payments. Keynes’ proposals were not adopted at Bretton Woods, with the proposal from his American interlocutor Harry Dexter White ultimately forming the basis of the Bretton Woods system revolving around the US dollar.

Yet, it appears that there is renewed interest in the architecture of transnational settlement systems, in light of the decision by the BRICS nations at the Kazan summit of October 2024, to proceed with the development of a national currencies-enabled trade payments system, BRICS Clear. A commitment from the BRICS nations to move forward with such a payments system remains a key part of the work of BRICS’ 2025 Secretariat, Brazil; the intent was again reinforced by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in recent comments after a meeting of CIS Foreign Ministers, in which he spoke specifically of the development of a BRICS payments system. Lavrov notes that such a system would be open to all, not just BRICS member states.

What can we learn from Keynes’ ICU and Bancor proposal? How may such ideas inform the design of BRICS Clear? What follows seeks to bring Keynes’ original conceptualisation to a wider contemporary audience and at the same time, open out a discussion about what a future currency multipolar world may look like. It does so by revisiting Keynes’ original design and intent; discussing the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights as a non-national global numeraire; and exploring the potential application of the fundamental ideas to the emerging BRICS environment.

Keynes’ ICU and Bancor

Historic Context

Keynes began drawing up the ICU and Bancor concepts in the early 1940s, in preparation for discussions about a post-war global financial system. Keynes’ overall attitudes towards trans-national economic relations were also scarred by the experiences of the 1920s and 1930s, in particular the pernicious financial conditions imposed on Germany by the victors of WWI at Versailles, which underscored his belief that in the interests of securing a meaningful peace, a stable international monetary system was needed. He recognised that imbalances in international trade, surpluses in some countries and deficits in others, were destabilising. He believed the existing gold standard and reliance on national currencies were inadequate for managing global trade. Keynes was also particularly concerned about the deflationary pressures that debtor nations faced, which often led to austerity, reduced economic activity, and social distress. Again, the lessons of Versailles were never far away. There has been a renewed interest in the Bancor concept of late.

Key Elements of the Proposal

Keynes’ broad concept involved an International Clearing Union (ICU) and an international reserve currency - what he called the Bancor. The ICU would act as a central institution for managing international trade and financial settlements. Each member nation would have an account with the ICU, denominated in Bancors. The ICU would track surpluses and deficits in trade balances. As for the Bancor itself, Keynes proposed it as the international reserve currency issued by the ICU. It would not be tied to any single nation's currency, reducing reliance on national monetary policies. Bancors would be used for settling international trade balances.

The system’s core design intent was to shape conduct towards system rebalancing, rather than create incentives for nations to accumulate trade surpluses. The system aimed to address trade imbalances by encouraging both deficit and surplus countries to adjust their economic policies, and ultimately address productive imbalances across nations. The underlying proposal was not about accounting balances as a normative objective in its own right, but that accounting imbalances were seen as ways in which nations could appreciate the extent to unevenness in global development for which all nations had shared responsibility.

The system sought to facilitate multilateral trade by creating a common mechanism for international payments, reducing the need for bilateral trade agreements. By establishing a global reserve currency and central clearinghouse, the Bancor system aimed to prevent competitive devaluations and ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ policies.

Keynes’ original proposal included detailed and specific parameters to enforce penalties and adjustments based on trade imbalances. These parameters were aimed at ensuring a symmetrical system where both creditor and debtor nations shared the burden of adjustments. Keynes’ system was designed to:

Prevent creditor nations from stagnating global demand by hoarding surpluses;

Ensure that deficit nations had time and resources to correct imbalances without resorting to harsh austerity; and

Foster a global system of equitable trade, where surplus and deficit adjustments were seen as mutual responsibilities.

By setting clear thresholds and penalties, Keynes’ Bancor concept aimed to avoid the systemic instabilities of the gold standard and the post-Bretton Woods system. While his plan was not implemented, these design principles remain a valuable framework for modern discussions on global trade and financial reform.

For creditor nations with surpluses in excess of 50% of their average trade balance over the previous five years in its ICU Bancor account, there would be penalties. Surplus holdings above the threshold would incur an annual interest charge. This would increase progressively with the size of the surplus. A creditor nation persistently exceeding the surplus threshold could face forced appreciation of its currency relative to the Bancor. This would make its exports more expensive and imports cheaper, encouraging trade balance correction. Surpluses beyond a certain threshold (e.g., 200% of the five-year trade average) might be partially confiscated and redistributed. Keynes suggested that this could go to a common fund for global development, so as to offset deficits of countries experiencing trade shortfalls.

Debtor nations, on the other hand, with accumulated deficits in its ICU account over 50% of its average trade balance over the previous five years would also face corrective measures. A key feature of Keynes’ proposal was to have a system that avoided the punitive austerity measures typically imposed on deficit countries that were the norm under the gold standard. He proposed that debtor nations could run an overdraft in its Bancor account up to 50% of their average trade balance, over the previous five years, without penalty. After this, interest charges would be applied, though these were lower than those imposed on surplus countries.

The underlying incentives / disincentives structure was not to punish debtor nations, but to facilitate the progressive relocation of productive capacity.

Deficit nations were to be given time to adjust their trade balances, avoiding immediate currency devaluation or deflationary measures. Again, this recognised that structure adjustment and industry development was not something that materialised in an instant. To assist in structural change, the ICU could provide technical assistance or loans for structural adjustments, such as improving export competitiveness or diversifying the economy. With all that said and done, if deficits persisted beyond certain thresholds (e.g., 100% of the five-year average trade balance), penalties would escalate, including higher interest charges on overdrafts and pressure to reduce deficits through trade policy adjustments or exchange rate changes.

Keynes’ proposal aimed to encourage global trade stability over time. Its built-in mechanisms aimed to discourage creditor nations from hoarding reserves and debtor nations from running unchecked deficits. Thresholds of imbalance were introduced to trigger automatic adjustment mechanisms. For surplus nations this included currency revaluation, import increases or even direct penalties. For deficit nations, structural reform support was to be provided, and eventually controlled adjustment to their currency if needed.

Trade balances would be monitored via nations’ Bancor accounts in the ICU. Nations’ accounts would be updated in real time, based on the flow of goods and services. Persistent imbalances above thresholds, as noted, triggered automatic reviews and adjustment mechanisms. Keynes further proposed that the ICU conduct regular assessments to evaluate compliance and recommend policy adjustments for surplus and deficit nations alike. A Global Fund was proposed, which would be financed by surplus nations, to assist debtor nations with industry development and to even out global demand.

SDRs as a De Facto Global Numeraire?

Keynes’ proposal for the Bancor and ICU was ultimately not adopted at Bretton Woods. Instead, the U.S. plan, led by Harry Dexter White, prevailed, establishing a system based on the U.S. dollar, pegged to gold, and the creation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Despite its rejection, Keynes’ ideas do find some embodiment in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), to the extent that SDRs already function as a de facto global non-national currency numeraire in specific contexts. The question is whether the SDRs could be adopted more broadly and form a cornerstone of a reformed international settlements system

The IMF SDRs have a number of core characteristics. Firstly, SRRs have a composite nature. They are not tied to a single currency but instead represent a basket of major global currencies (currently USD, EUR, RMB, JPY, and GBP). This makes them relatively stable and less vulnerable to the volatility of any one currency. The SDRs function as a valuation standard, and are used as a unit of account by the IMF and some other international organisations, serving as a measure for exchange rate calculations and reserves valuation. Lastly, SDRs fulfil the function of a reserve currency. SDR allocations are distributed to member countries, enabling them to access liquidity without relying on volatile capital markets or currency reserves.

The SDRs also perform the role of a numeraire in certain circumstances. As noted SDRs provide a common standard for financial transactions, reporting, and international reserves. By offering a currency-neutral benchmark, SDRs reduce the dominance of national currencies (especially the USD) in certain contexts, mitigating currency-related trade risks. They can therefore offer stability in trade and finance.

What then could SDRs contribute in the context of an evolving or a reformed international settlements system? In theoretical terms, SDRs could replace national currencies (e.g., USD) as the primary reserve asset and settlement currency, reducing currency-based power imbalances. SDRs could act as a numeraire for clearing international payments, aligning well with Keynes’ Bancor concept. In such an environment, countries could transact in SDRs instead of bilateral currencies, avoiding the risks associated with dollar dependency. The SDR’s basket-based valuation would provide a buffer against individual currency fluctuations, ensuring stability in a new settlement system.

If these are the theoretical uses and benefits, there are a number of challenges for effective SDR integration. Firstly, SDRs are tightly linked to the IMF, which is seen by some countries (especially within BRICS) as disproportionately influenced by advanced economies. The IMF’s conditionalities on credit and its governance structure may deter emerging economies from fully embracing SDRs in a new system. Secondly, SDRs are relatively limited in volume, compared to global trade volumes, constraining their immediate utility as a global settlement currency. Lastly, even if there was a desire to incorporate SDRs into a reformed global settlement system, adapting the SDR to function as a digital, widely accessible currency in real-time settlements would require significant technological and institutional innovation.

The challenges of incorporating SDRs into a reformed settlement system may prove to be insurmountable. In this situation, adaptation may be considered including decoupling SDRs from the IMF. This would involve the establishment of a neutral international clearinghouse to manage SDRs independently of the IMF, reducing geopolitical resistance. Alternatively, reform of IMF governance may be called for, including revisiting the IMF’s voting structure to ensure equitable representation, making SDRs more acceptable to emerging economies. Thirdly, there is likely to be a need to expand the SDR basket and include more currencies. Additional emerging market currencies could be added to the SDR basket to make it more representative of global trade patterns. Fourthly, linking SDRs to commodities as a valuation mechanism or formula may enhance the SDR’s stability and appeal to resource- or commodity-rich countries. Lastly, it is conceptually possible for a reformed LDR regime to run in parallel to alternative systems. This would see SDRs coexisting with a newly created settlement current (e.g. a BRICS settlement currency, on which more later), enabling gradual adoption without disrupting the existing system.

If SDRs remain too constrained by ties to the IMF, a new settlement framework could nonetheless emulate some of the structural features of SDRs. For instance, regional settlement currencies could be created. BRICS or other trading blocs, such as the Africa free trade zone, the RCEP or regions like Latin America, could create their own SDR-like currency basket, designed specifically for regional trade and settlement. If concerns exist about centralised or imbalanced governance, it is conceivable that SDRs could be digitalised and issued and tracked on a blockchain, enabling real time transactions and distributed management. A hybrid model could also be envisaged in which SDRs are used for reserve purposes while introducing a separate global numeraire for operational settlements, maintaining continuity with the current system.

While SDRs possess many qualities that make them suitable for a reformed international settlements system, their linkage to the IMF's governance and policy framework poses significant challenges. To address these, either the SDR system would need substantial reform (e.g., decoupling from the IMF) or new, SDR-inspired frameworks could be developed.

Revisiting the Bancor Concept: a Digital Universal Settlements Denominator (dUSD)

Concept

We now return to Keynes’ original proposal as a launching point to discuss some of the possible features of a modern settlements currency or numeraire. Given advances in technology, a digital bancor-like instrument could be envisaged. Such an instrument could be called a (Digital) Universal Settlements Denominator (a dUSD). A dUSD would be a digital, supranational bank-to-bank unit of account that could function as a medium of exchange for cross-border settlements and a reserve asset. Using blockchain or distributed ledger technologies, the currency could ensure transparency, security, and independence from any single nation. It would serve as a numeraire for valuing trade and resolving payments within BRICS and potentially other countries.

Such a system would have some advantages for BRICs and associated nations, seeking to transition to a settlements system that is less prone to capricious weaponisation. It would reduce national reliance on the U.S. dollar, addressing concerns about exchange rate volatility and geopolitical risks. It could also create a level playing field for participating member states, avoiding the domination of one national currency over others. In light of ongoing dollar weaponisation, and now the weaponisation of trade, there is a growing imperative to scale-up the institutions necessary for alternatives.

A dUSD-based system could adopt some of the design principles from Keynes’ original concept to penalise surplus and deficit nations. For deficit nations, they could be allowed to borrow the dUSD from a BRICS Clearing Union (BRICS Clear) at low interest rates, encouraging economic adjustments without harsh austerity. Additionally, conditional adjustments could be introduced focused on growth and investment rather than austerity. Going a step further, targeted assistance could be directed whereby a portion of surplus funds could be committed to investment projects in deficit countries to enhance productivity and reduce dependency. For surplus nations, there could be holding hosts for excess balances. In this case, holding fees or negative interest rates could be imposed on nations with excessive reserves of the eUSD, incentivising reinvestment or consumption. Stronger incentives could be designed to make the use of surpluses to fund sustainable infrastructure or technology initiatives across BRICS attractive. Lastly, in the event of incentives failure, mandatory reinvestment could be enforced whereby surplus nations are required to reinvest their balances in agreed-upon multilateral development projects within BRICS or globally.

Such an operational design would require the establishment of a BRICS clearing union. The BRICS Clear proposal is along these lines. Such a clearing union is a collegiate body modelled after Keynes’ ICU but designed to manage trade and financial settlements between BRICS nations. Judging by the remarks of Sergei Lavrov, non-BRICS nations would be welcome to work with the platform as well. In BRICS Clear, accounts for each member nation would be denominated in the settlement currency. Adjustment mechanisms that allow participating nations to negotiate adjustments to their policies to avoid imbalances becoming entrenched would need to be created. Given advances in contemporary information technology, it is conceivable that AI and big data analytics capabilities could be used to provide real-time monitoring and predictive insights on trade flows and potential imbalances. Lastly, such a clearance union could operate with a dynamic exchange rate framework whereby a managed floating exchange rate system is tied to the settlements currency to allow for gradual adjustments while maintaining stability.

The dUSD settlements currency concept aligns well with BRICS’ goals of reducing dollar dependency and enhancing financial integration. The use of such a settlement currency to settle trade within the BRICS Clear system, avoids the need for intermediaries like SWIFT or reliance on US dollar-based accounts. This system is likely to enhance compatibility with other alternative systems such as China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) and Russia’s SPSF. The attractiveness of such a system could be further enhanced by enabling broader participation and use. Other nations (e.g., global south countries) could be invited to join the system, fostering a more inclusive global financial system. Consideration would also need to be given to how such a settlement currency is linked to existing currencies. For example, the dUSD could be pegged to a basket of BRICS national currencies or commodities like gold, though there is no in principle need for a commodity peg given that such a non-national settlement system is effectively guaranteed by national fiat.

Transition and Governance Challenges

The transition to such a payments system is not without challenges. At the outset, effort will need to go into aligning the diverse economic priorities and trust levels amongst BRICS members. A distributed ledger-based system, modelled on the approach developed as part of the mBridge initiative, shows the way to building institutions and technologies that can be adopted in conditions of relatively low trust. The use of such technologies would also contribute to enhanced transparency and equitability in governance of the system, so as to prevent dominance by any one member nation. The current capricious nature of US policy making also creates conditions that could impel nations to progress post-haste to addressing these issues, and striking compromises that at a minimum enable non-USD national currency-based settlements to scale. Recent volatilities in American policy making and its impact on the stability of US dollar-denominated assets valuation also raises further concerns as to the relative robustness of existing institutions.

Lastly, so as to enable it to become more entrenched, the BRICS Clear system will need to gain recognition from non-BRICS nations, so that the dUSD is accepted as a valid reserve and trade currency. This is an incremental process that would go towards expanded global acceptance. The centrality of partial RMB internationalisation will play a role in this process, which is something I will come back to in a future article.

The new system would be governed in a manner that would ensure compliance with adjustment protocols, which are discussed below. Multilateral oversight is critical, as one of the political aims is to mitigate the risk of power concentration. Decisions on penalties, currency adjustments, and redistribution of dUSD reserves would be managed collectively by member nations, ensuring fairness. Transparency on data would also be a necessity. Regular monitoring of trade balances and dUSD reserves would be needed to ensure the timely identification of imbalances, allowing for preemptive measures. Lastly, a common pool funded by penalties on surplus nations could be used to stabilise deficit nations, fund global development, or address systemic risks.

Should there be concerns about speed or adjustment, let us not forget that within 3 years, almost all of Russia’s trade has been effectively de-dollarised, and transacted using Ruble, RMB and a few other national currencies. Over 85% of trade within the Commonwealth of Independent States is undertaken with national currencies. Over 70% of Russian trade with ASEAN is also settled in national currencies. China’s RMB denominated trade now accounts for over 54% of its trade. These are not trivial developments, and show that in a relatively short space of time, when there is a need, the transitions can be made.

Exchange Rate Determination

Mechanism for Initial Exchange Value Determination

Perhaps one of the most critical issues that requires resolution goes to how exchange rates are determined.

When a nation joins a clearance union system, the initial exchange value of its national currency against the settlement currency can be determined using a number of possible methods. These include either an economic indicators approach or a negotiated entry framework. In terms of the latter, when a new nation enters, its exchange value could be negotiated among existing members of the union, based on both economic data and strategic considerations, such as its expected contribution to trade and investment flows. The alternative would be the use of various economic indicators. For example:

Purchasing Power Parity (PPP): The initial rate could reflect the relative purchasing power of the currency within the domestic economy, ensuring alignment with its real economic value;

Trade Balance and Reserves: Consider the nation’s trade balance, foreign exchange reserves, and existing monetary policies to set a rate that avoids immediate distortions in trade;

Monetary Base and GDP Ratio: Use the ratio of the monetary base to GDP as a measure of the currency’s underlying value and its economic backing; and

Basket Benchmarking: Peg the value to a weighted basket of participating countries’ currencies and commodities (e.g., gold, oil) to create a common reference point.

Without advocating one or the other, the simple point here is that there are ways and means; and indeed, where there is a will, there will be ways.

Mechanism for Periodic Adjustment

Once the system is operational, periodic adjustments to exchange rates would ensure fairness and adaptability. These could be based on automated adjustment mechanisms or periodic reviews undertaken by the governance body. Automated mechanisms could include:

Trade-Weighted Adjustment: Exchange values are adjusted based on changes in the country’s trade balance. Surplus or deficit trends trigger gradual revaluation or devaluation;

Inflation and Interest Rate Parity: Adjust the rates to account for differences in inflation and interest rates between participating countries to maintain real competitiveness; and

Moving Averages: Use a weighted moving average of currency performance over time to smooth out short-term volatility and prevent abrupt changes.

Annual or Biannual Reviews could become par for the course, when the governing body or its delegate (e.g., the BRICS Clearing Union or a similar governing body) reviews the rates periodically, considering updated economic data and market dynamics. Member nations would be invited to submit economic reports, and adjustments are made through consensus or weighted voting, ensuring transparency and inclusivity.

At the same time, the system could operate a form of a managed float system that allows the dUSD’s value against national currencies to fluctuate within a defined (and narrow) band, with interventions to maintain stability if deviations exceed predefined thresholds.

Accommodating New Entrants

When new nations join, their inclusion must be managed carefully to avoid destabilising the system. An initial provisional rate is likely needed as a first step. Such a provisional exchange rate could be based on the nation’s economic fundamentals and a temporary adjustment buffer, which can be refined after a trial period. A new member’s currency could also be introduced in phases, starting with limited trade settlements before being fully integrated into the union’s currency pool. Lastly, it may be prudent to establish some form of membership adjustment fund to assist new entrants in managing exchange rate shocks during the initial adjustment period, smoothing their integration into the system.

Long-Term Mechanisms

Over the longer run, adjustments in relative exchange rates are likely to be impacted by consideration of factors such as a dynamic basket index, where participating national currencies’ relative values are regulatory adjusted based on the evolving economic significance of members. Critically, as noted earlier, if one of the principal aims is to encourage system adjustments to mitigate the risk of sustained or intractable imbalances, nations will need to be encouraged to manage domestic policies in ways that reduce the frequency and scale of rate adjustments. Lastly, it is conceivable that advanced data analytics can be used and economic modelling to predict when adjustments are necessary, minimising reactive changes and fostering stability.

Key Challenges and Mitigation

The viability and attractiveness of such a system depends on the ability of member states, through the design and operational processes, to address political and other sensitivities. In today’s fraught international environment, a transparent, rules-based process can mitigate disputes over exchange value adjustments and ensure fairness. There is also a need to address risks of speculation and manipulation. Here, capital controls and surveillance mechanisms (data analytics) could be introduced to prevent market actors from destabilising the system. Lastly, as joining new systems invariably involves some adjustment costs, the platform itself would need to provide technical and financial support to help new members align with system requirements.

By combining these mechanisms, the system can maintain stability while adapting to economic shifts, ensuring fair participation for all members. This approach would also provide a strong foundation for the BRICS or any other multilateral settlement system to expand and operate sustainably.

Concluding Reflections

This discussion has not been an attempt to present a blueprint for a BRICS clearance union. Rather, I have sought to draw on Keynes’ original proposal for an ICU from the 1940s to illustrate just how such a concept could be mobilised under contemporary circumstances. The discussion has highlighted a range of issues, focused principally on institutional governance, incentive / disincentive mechanisms to encourage adjustments across national borders and possible mechanisms for the adjustment of exchange rates.

I have no doubt that these issues, and more, are presently those that are occupying the minds of finance ministers, finance institutions and policy makers in BRICS nations as they continue work on bringing the vision of BRICS Clear to life. The point too has been to demonstrate that the issues aren’t new, and that there are plenty of approaches that can be worked through to addressing them. There are no insurmountable hurdles, in other words.

That BRICS nations have robust real economies, replete with raw materials, energy resources, human capital and industrial capabilities point to the capacity of these nations and those that they interact with, to successfully underpin a national currency based trading platform, which revolves around a non-national currency numeraire and a multipolar governance architecture undergirded by distributed ledger technical foundations. The capacity to exchange real use values is what ultimately underpins confidence in the foundations of such a system.

America’s longstanding trade deficits have been financed through the issuance of US dollars through Congressional appropriations and commercial bank credit creation. These IOUs have found favour globally as holders of surplus dollars could use them to purchase energy or technologies, or deploy them into yield generating financial (or fictitious capital) assets. Whether these have been in bonds, stocks, foreign exchange or derivatives, institutional and policy stability has made it viable for nations to hold US dollars and USD-denominated financial assets far in excess of their trade settlement needs. Both of these underpinnings have eroded in recent years. Energy and technologies can be accessed without US dollars. In these circumstances, with increasing volatility in the medium- to long-term exchange value of USD-denominated financial instruments, nations are increasingly wondering whether there’s any point in holding onto these, except where needed to ‘do business’ with the United States. The yield on these financial instruments is paid in American IOUs (that is, dollars), and when these IOUs are no longer as useful as they once were, the attractiveness of either dollars or dollar-denominated financial instruments diminishes.

The volatility of the US dollar, bonds and stocks in the wake of Trump’s so-called reciprocal tariffs announcements and subsequent backtracking has sent a strong signal globally that risk-free is no longer a moniker that can be applied to US dollars or financial assets. Financing alternative trading networks can be achieved without exposure to the vicissitudes of American capital markets, because these capital markets are the result of the expanded issuance of US dollars over time to finance American purchases, where the future exchange value of these dollars is no longer certain.

That US dollars remains, on the face of it, the global reserve currency is more a question of form over function. The difference between form and function is something to which I will return in a subsequent article. Meanwhile, non-USD cross border settlements systems continue to expand, and the lessons and insights from Keynes’ original Bancor and ICU proposal seem particularly apposite today, as BRICS works to consolidate a new platform that can facilitate the ongoing progression of currency multipolarity.

This is a detailed and comprehensive overview of what would greatly improve the existing financial protocols for the coming multipolarity world. Many proposals will be made — and the adoption of a new non-USD is a bit of ways off (imho).

To the extent that Warwick follows the China-driven blockchain alternative to the commercial bank/Swift system(based on BIS/mBridge) — I would be interested in your assessment. Secure, non-USD trade transactions that avoid the western banking system seem to be an enormous step forward in the trade transactions that are the bread-and-butter of the multipolar world. Because the transactions are cleared almost immediately (same day) versus the 5-day Swift, currency risk is not only reduced but the invisibility to western banks is an enormous advantage as the largest of the banks (Morgan, Citi, HSBC) all have active currency trading desks. These banks enabled (as just one example) the Soros play against the Bank of England which Bessent was possibly involved with (1992), which appeared to have netted Soros $1 billion (closer to $4 billion today).

Do we need a long-term store of value with (near) infinite sink? I'm thinking of countries like Japan which run up persistent surpluses as one decade, a megaquake will hit and they'd need their accumulated savings to rebuild whilst their industrial base is wrecked.

A followon concern is security of such value-stores ... if a single nuke can destroy it (think DUNE, he who can destroy the spice, controls the spice) then it creates a vulnerability. Which leads to the logical conclusion that nuclear arms reduction to prevent bad coercive behaviour is an issue.