Context: There’s a lot of misleading and misinformed commentary about China’s economic development model and experience. Much of it is grounded in mainstream economics presuppositions, which - while usually not explicitly articulated - play an oversized role in framing the diagnostics and the prognostics. In this essay, I offer an alternative narrative frame, which addresses the key issues raised by mainstream commentary, and in doing so, demonstrates that there are good reasons to ignore much of the claims made by the mainstream commentators.1

Introduction

China’s continued economic development and growth is often met by incredulity, disdain and disbelief from a wide cross section of mainly western commentators and observers. It defies mainstream western diagnosis and prognosis. At various times over the past few years, mainstream commentators have levelled a number of claims about China’s economic model. Some have argued that China’s model is based on excessive, unsustainable and wasteful investment, at the expense of household consumption. On this reasoning, households have been deprived of incomes to subsidise investment, either by state authorities or enterprises. This then leads to a claim about excessive capacity, which, so the argument goes, can only be addressed through export expansion via an aggressive form of neo-mercantalism. Lastly, this set of claims is rounded off by the argument that Chinese household savings rates are excessive. Ultimately, the argument is that China’s savings rate is the cause of America’s merchandise goods trade deficit.

All these critical claims notwithstanding, China’s economic development has been characterised by sustained high growth rates, massive infrastructure investments, and an evolving transition from an export-led model to a more domestically driven economy. None of this lends itself to the mainstream claims. Rather than seek to understand the Chinese economic development experience and trajectory, the mainstream response has been to either speak of an impending collapse or pursue an argument about China’s “imbalances” as the root cause of global sub-optimality.

These claims should not be accepted without critical analysis. This essay contributes to this effort by articulating an alternative series of narrative frames that better explain China’s development experience and trajectory. It does this by rejecting some of the key theoretical propositions that underpin the mainstream story.

For those with a background in heterodox economics, the influence of Robinson (on endogenous money in particular), as well as Kaldor and Sraffa (on growth) will be noticeable. For those without this background, be assured that this essay does not get bogged down in technicalities, so as to make the broader argument accessible. This essay deliberately eschews presenting masses of statistical data, which could readily be found in various places, but rather focuses on articulating a concept-driven explanatory framework and its logic.

What are we seeking to understand?

We are basically seeking to explain China’s economic development experience and trajectory. The experience and trajectory has involved an evolving transition from investment-led to consumption-led growth as autonomous demand evolves. China’s long-run trajectory evidences the following broad pattern or phases:

Early growth phase (1980s–2000s): Export-driven accumulation and state-led infrastructure investment.

Mid-phase (2010s–2020s): Shift toward technology-intensive industries and urbanisation-driven domestic demand.

Future phase (2030s-): Transition toward higher domestic consumption, green energy investment, and services-led growth.

The core proposition in what follows below is that China’s long-run trajectory can be explained as being based on investment demand driven expansion characterised by rising household incomes and domestic consumption, whereby a relatively stable rate of savings is a residual of rising real incomes and competitive markets dampening prices.

At the heart of this alternative analysis of China’s economic growth trajectory and model is to recognise that autonomous or exogenous demand is the primary growth driver. In China’s case, this has involved State-led investment in infrastructure, urbanisation and industrial policy playing the key role of exogenous demand. Publicly owned financial institutions have been central to this economic development model. Exports have supplemented state-led investment as an external demand stimulus, especially during the 1980s through to the mid-2000s, though this has receded in recent years as government-driven innovation and green energy investments represent new sources of exogenous demand.

Secondly, as China’s autonomous demand grows, it triggers induced private investment in supply chains and production networks. Thereafter, rising incomes from investment-led employment have also supported induced household consumption, although this has historically lagged behind investment. Consumption levels is a function of investment, with savings as a residual (which I discuss below). Rising consumption has taken place as output has also expanded, and when combined with competitive markets, there is little inflationary pressure in the system. In China’s development experience, productive capacity has been able to adjust endogenously to autonomous demand. In practical terms, this has involved State coordination of capital investment (SOEs, planning mechanisms) to help avoid over-accumulation crises seen in other developing economies and industrial upgrading policies (e.g., Made in China 2025), reflecting an evolving pattern where autonomous demand shifts toward new high-tech sectors.

In this experience, as in all cases, we see a distributional trade-off between profits and wages. China’s early growth (1980s–2000s) was profit-led, with high capital accumulation supported by low wage shares and household consumption. Recall that household consumption as a proportion of GDP fell between the 1950s through to the early to mid 2000s. More recently, policy shifts (common prosperity agenda, urbanisation, and social spending) suggest a transition toward a shift back in favour of rising labour claims on value added (at the expense of capital / profit), where induced household demand plays a larger role. Consumption share to GDP was quite stable in the 1980s then declined slightly in the 1990s. The large decline was, broadly speaking, in the decade 2000-2010. Then the ratio rose until the Pandemic.

Investment as Autonomous Demand Driver

The Role of Fiscal Policy in Infrastructure Investment

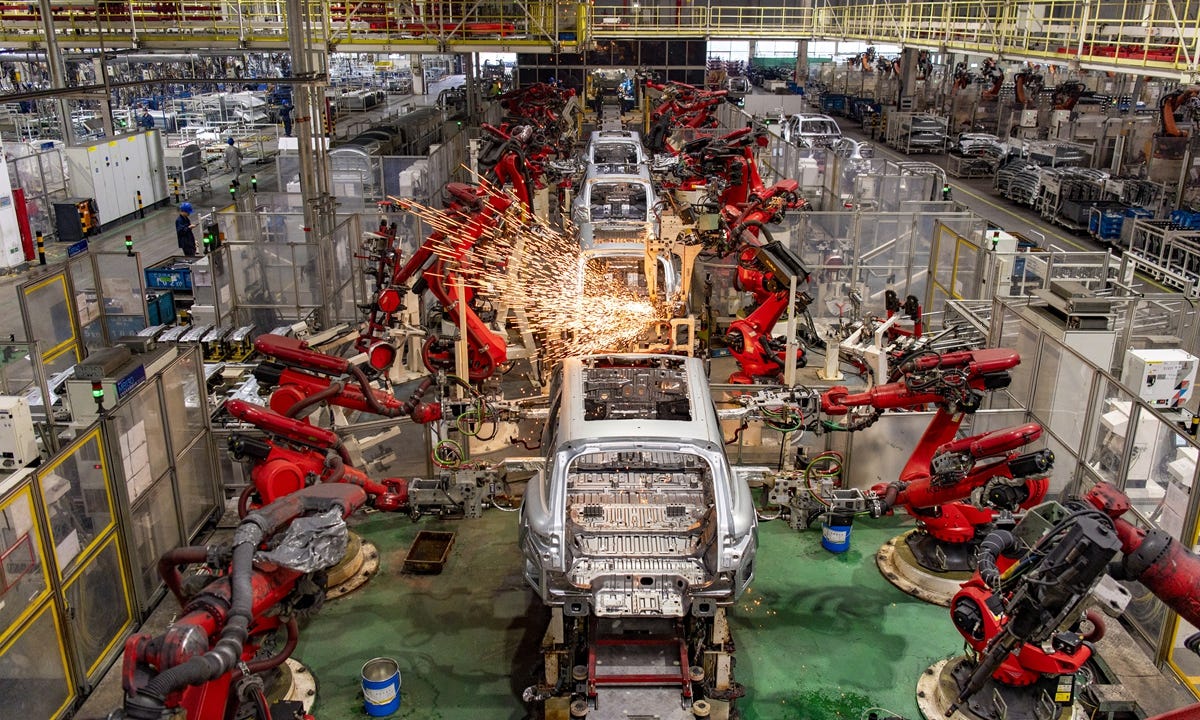

In China’s economic development, government investment in transport, energy, and telecommunications have played pivotal roles. China’s rapid economic expansion has been underpinned by massive fiscal-driven investments in core infrastructure. This includes high-speed rail, highways, and urban transit which enhance regional connectivity and productivity; power generation and energy networks thereby supporting industrialisation; and broadband and telecommunications thereby enabling digital economy expansion.

These infrastructure investments exhibit strong demand multiplier effects and contribute to long-run productivity growth, where increasing output leads to higher efficiency gains. Thus, infrastructure investment expands productive capacity and generates cumulative causation effects, reinforcing manufacturing-led growth. Furthermore, public infrastructure acts as autonomous demand, sustaining long-term private sector investment. Finally, infrastructure lowers business costs, supporting profit expectations and sustained capital accumulation.

China’s fiscal policy regime also acts as something of a stabilising or counter-cyclical mechanism. During downturns, government spending is ramped up via local government investment vehicles and SOEs. This prevents underutilisation of capacity, stabilising aggregate demand. Here, government investment serves as an exogenous stabiliser, preventing demand shortfalls. Unlike in purely market-driven economies, where investment depends on profit expectations, China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) provide a structural mechanism to maintain investment demand independent of immediate market conditions. This breaks the profit-driven investment constraint, suggesting that in China’s case, investment is truly exogenous.

Public Banks

A particularly critical aspect of China’s growth model has been the role of publicly owned financial institutions in driving investment in enabling public goods and the increasing importance of domestic drivers of growth, and the big push in energy efficiency and Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROEI) improvements. Investment is not constrained by savings but rather by the availability of resources and the capacity for productivity growth without triggering inflation.

A defining feature of China’s growth model is the central role of state-owned policy banks (such as the China Development Bank, Export-Import Bank of China, and Agricultural Development Bank of China) in financing investment. Unlike in market-driven economies, where private financial institutions allocate credit based on profitability considerations, China’s policy banks operate as instruments of state-driven credit allocation, channeling funds to strategic sectors. Such investments in energy, transport, and telecommunications infrastructure enhance long-term productive capacity, reducing costs and enabling sustained expansion.

In contrast to mainstream exogenous money models (where savings determine investment), the endogenous money approach sees bank lending as creating deposits, meaning that financing is not constrained by prior savings. Policy banks in China expand credit to enterprises and local governments, ensuring that investment remains high, even when household savings rates are elevated. This aligns with various heterodox perspectives, where investment is autonomous and drives demand, rather than being limited by available savings. Since investment leads the cycle, the availability of credit via policy banks ensures that investment remains the anchor of demand growth. It's worth noting that from a neo-Kaleckian perspective, if private firms face profitability concerns, state-backed credit allows investment to persist even during downturns, preventing stagnation.

In mainstream commentary, high savings can constrain demand. However, in China, policy banks and government credit fill demand gaps by directing investment into infrastructure, industrial upgrading, and strategic sectors. Endogenous money creation is the reality; as such, savings are not a constraint on investment. Firms and local governments continue investing not because of immediate profit expectations, but because of state-backed funding availability.

Thus, China’s financial system institutionalises a mechanism whereby investment remains an exogenous driver sustained by state-directed credit.

Unlike market-driven financial systems, where credit allocation is often cyclical and profit-driven, China’s state-controlled credit mechanism ensures steady investment flows, preventing underinvestment in critical sectors. Infrastructure investment as it enhances economic efficiency and lowers costs for businesses and households, reinforcing the growth process. Improvements in transportation (high-speed rail, roads, and ports), energy production, and telecommunications increase economic connectivity and reduce transaction costs, sustaining long-term expansion. Since savings adjust as a residual to investment, these investments do not face financial constraints as long as productivity gains keep inflation in check. The point here is that state-owned financial institutions - the major commercial banks - have played a central role in credit expansion and channeling.

A Comment on Debt and related themes

A common critique of China’s economic model is that high levels of public investment have led to excessive public debt and inefficient capital allocation. This critique is rooted in mainstream economic assumptions that public debt must eventually be “paid back” through taxation, that it crowds out private investment, or that it signals misallocation of resources. However, this perspective fundamentally misunderstands the nature of public debt in an economy where money is endogenous and how public investment operates in China’s growth model.

Public debt is not like private debt. In the private sector, debt must be repaid out of future income. If an individual or a firm takes on too much debt, it constrains their ability to consume or invest in the future. Public debt, in contrast, is not a constraint in the same way because the state, through its financial institutions, creates money endogenously. We can also note that mainstream economics assumes that rising public debt requires future taxpayers to cover repayment. But public debt does not necessarily require taxation to repay it. In China’s system, as discussed above, public investment is largely financed by policy banks and state-owned financial institutions, which create credit endogenously. As long as the investment enhances productivity and future output, it more than offsets its financial cost through long-term economic gains.

Public investment thus creates productive capacity that in effect pays for itself. Infrastructure, energy, and technology investments expand the real economy, allowing future income to grow faster than debt servicing costs. China’s investments in transport, telecommunications, and energy have lowered business costs and improved economic efficiency, ensuring a high return on investment over time. For example, investments in high-speed rail reduce logistics costs for businesses, improve labor mobility, and create a more integrated market—this leads to long-term economic gains that more than justify the initial borrowing.

Mainstream analysts focus on the debt-to-GDP ratio, assuming higher debt levels indicate risk. This leads to observations about ‘fiscal room’ etc., but in fact largely misses the point. A more relevant measure is debt-to-productive-assets. If debt is being used to create assets that enhance future economic output, it remains sustainable. Unlike Western economies that borrow largely for current consumption or financial speculation, China’s public debt primarily funds productive infrastructure and industrial investment. Public debt only becomes a problem if it fails to generate productive assets that improve future output. Since China’s debt is tied to long-term investments that enhance economic efficiency, it does not pose the same risks as unproductive borrowing in consumption-driven economies.

On questions of investment inefficiency

Critics argue that China’s public investment model leads to “wasteful” or “inefficient” projects, particularly in infrastructure. However, this critique is largely based on static, short-term financial metrics rather than dynamic, long-term economic outcomes. Adopting different time horizons where evaluations are central to alternative understandings of whether an investment is ‘efficient’ or not. A short term approach would look at whether projects generate immediate financial returns in the short term. A longer term approach would assess whether investments create long-term economic multipliers by enabling future productivity, income growth, and cost reductions.

Thus, framed by a short-term lens the focus would be on short-term financial inefficiencies (e.g., under-utilised transport infrastructure at the start), which are then misinterpreted as “waste.” Conversely, a longer time horizon evaluates the extent to which infrastructure investment today lays the groundwork for things such as future urbanisation, industrial expansion, and economic integration. For instance, high-speed rail and expressways were initially under-utilised but became critical enablers of regional economic growth. Without these investments, economic activity would have been constrained, leading to higher long-term costs and inefficiencies.

Against this background, the Chinese experience suggests that public debt in an endogenous money system is not a rigid constraint. China’s state-led financial institutions create credit to support productive investment. Public investment in infrastructure and industrial capacity ensures that debt-financed growth expands economic potential, rather than burdening future generations. The efficiency of investment should not be judged solely by short-term financial returns but by its long-term contribution to economic development and productivity growth. Claims of wasteful investment misunderstand the role of proactive, forward-looking planning in creating future economic opportunities. Thus, the common Western critique of China’s debt and investment model misses the fundamental difference between public and private debt, as well as the long-term structural benefits of state-led investment.

Savings as a Residual, Not a Constraint on Investment

One of the most interesting features of the Chinese political economy is the fact that savings rates have been relatively stable amidst rising incomes. Since household incomes are rising in real terms, consumption grows while savings rates remain largely unchanged. This stabilises the flow of funds into investment in reaction to rising consumption, while mitigating the risk of excess consumption-driven inflation.

A key insight from a range of ‘heterodox’ economic theoretical perspectives is that savings do not constrain investment. Instead, investment decisions determine income, and savings adjust accordingly. China's high investment rates are not limited by household or corporate savings but are enabled by credit creation by the banking system.

This aligns with the endogenous money perspective, where the banking system creates deposits as loans are issued. The persistence of high savings rates in China is largely due to strong income growth and stable prices. As households and businesses earn more, their absolute level of savings rises, even if their savings rate remains stable or at times even rises.

In a scenario where investment growth drives capacity expansion faster than consumption growth, the resulting excess supply relative to demand would exert downward pressure on prices. This mechanism can lead to stable or moderately rising household savings rates, provided that real incomes also rise. The logic follows several interrelated dynamics.

Firstly, when productive capacity expands faster than consumption demand, firms face competitive pressures to lower prices to sustain sales. Deflationary or disinflationary effects emerge, keeping the cost of goods relatively stable or even declining in real terms. Then, since consumption is a function of investment-led growth, wage income rises with investment expansion. Therefore, even if households maintain a stable marginal propensity to consume (MPC), their absolute level of consumption increases because of rising wages. Lower prices further increase real purchasing power, meaning households can meet their consumption needs without reducing their savings rate.

Secondly, as long as wages grow at a rate equal to or exceeding inflation, and essential goods become more affordable due to supply expansion, households can maintain a steady or slightly increasing savings rate. In contrast to demand-constrained economies, where households may reduce savings to maintain living standards, in this scenario, they do not need to dis-save to sustain consumption growth. Consequently, we see the persistence of investment-led growth with high savings.

The primary constraint on investment is not the availability of savings, but rather the availability of resources and the capacity for productivity growth, while ensuring price stability. Investment growth depends on the availability of productive resources—energy, labor, raw materials, technology, and infrastructure—that can support expansion. If the economy faces resource shortages, investment may be constrained, even if there is abundant credit or savings. In China’s case, massive state-driven investments in infrastructure (transport, energy, telecommunications) and industrial capacity have helped expand the resource base, providing the foundation for continued investment. Furthermore, investment can only grow at a sustainable rate if there are improvements in productivity—i.e., increased efficiency in resource utilisation. Productivity growth allows the economy to absorb the additional output via rising incomes, and capacity created by new investments is absorbed without triggering inflation. China’s focus on technological upgrading and infrastructure development has driven productivity growth, allowing the economy to scale while mitigating inflation. If investment expands too rapidly without corresponding productivity growth, or if there is too much demand relative to supply capacity, it could lead to inflationary pressures. China has managed this through a combination of price control measures, capacity expansion, and the gradual absorption of surplus labor (e.g., migration from rural to urban areas), which helps mitigate inflation risks while ensuring that supply keeps up with demand.

Competitive Markets, Supply Growth, and Price Stability

In competitive markets where investment growth sees capacity expand faster than consumption, but consumption in real terms also expands as a function of investment growth, there would be downward pressure on prices resulting in stable or moderately rising household savings rates as households can meet their needs from rising income while maintaining a constant or near constant rate of savings.

China has managed to sustain rapid growth in household incomes without triggering high inflation. This is likely a result of the role of increasing returns to scale and supply-side expansion in maintaining price stability. Investment-led expansion continuously raises productive capacity, ensuring that demand growth does not outstrip supply. Rather, output capacity is continually ‘leading the way’. Economies of scale in manufacturing and infrastructure projects reduce unit costs over time. Competition in export and domestic markets forces firms to keep prices competitive despite rising wages. Unlike demand-pull inflation scenarios, China’s productivity improvements ensure that real wage growth does not translate into uncontrolled price increases.

In competitive markets where investment expands capacity faster than consumption, but consumption still grows with rising incomes, downward pressure on prices allows households to maintain or slightly increase their savings rate without sacrificing consumption growth. This reinforces an investment-led growth model with a persistent surplus in household savings. With price stability or mild deflation, real wages rise without an equivalent increase in nominal wages, meaning households can sustain their consumption patterns while maintaining a stable savings rate. Since prices do not rise significantly, households do not need to dissave to maintain their living standards.

China’s investment-driven growth model demonstrates how investment can be sustained even with high savings rates if there is sufficient availability of resources and productive capacity. State-driven investments in infrastructure and technological development have enhanced the supply side of the economy, ensuring that investment can expand without causing inflation. Government policy has created conditions for continuous productivity growth while maintaining price stability, which further supports the ongoing expansion of investment. Thus, China’s ability to maintain high investment growth is not limited by the availability of savings, but by the capacity to absorb the investment efficiently through improved productivity and resource management, all while keeping inflation in check.

The Increasing Role of Domestic Demand in Driving Growth

China’s growth model is shifting from an export-driven strategy to one centered on domestic consumption and investment. This evolution has been unfolding for much of the past 15-20 years. Some aspects of this shift can be understood in terms of a growing role of wage-led growth and demand-side dynamics. Rising wages and middle-class expansion are driving higher domestic consumption. Public sector-driven investment in health, education, and urban development is fostering internal demand growth. Technological upgrading and innovation policies are enabling China to move up the value chain, reinforcing domestic production capabilities. The gradual diversification away from exports reduces vulnerability to external demand shocks.

Expanding Household Incomes and Consumption: The Spatial and Demographic Dimensions of China’s Growth Model

A critical counterpoint to mainstream critiques of China’s economic model is the steady expansion of household incomes and consumption, which has accompanied the country’s investment-led growth. While some argue that China’s economy suppresses household consumption, the evidence suggests a broad-based and regionally inclusive rise in living standards—one that has not only lifted overall household incomes but also reduced inequality, expanded consumption beyond major cities, and created a younger, more geographically dispersed middle class.

The Macro Story: Rising Aggregate Household Incomes and Consumption

China’s rapid economic expansion has translated into substantial increases in real household incomes over the past two decades. The basic empirics show:

Real per capita disposable income has grown at an average annual rate of around 6-8% over the past 15 years, significantly outpacing inflation.

The share of labor income in GDP has rebounded since 2010, following earlier declines in the 1990s and early 2000s, reflecting rising wage levels and improving worker compensation.

Household consumption expenditure has grown in tandem with incomes, shifting China away from an economy overly reliant on exports or heavy industry toward one increasingly supported by domestic demand.

Investment as an Enabler of Household Income Growth

As discussed, investment-led growth does not crowd out consumption—rather, it enables it. Strategic public and private investment in industrialisation, infrastructure, and services has created high-wage employment and supported long-term income growth.

Urbanisation, together with expansion of advanced manufacturing and high-tech industries, has provided higher-paying, higher-skilled jobs, particularly in cities. At the same time, investment in services—including education, healthcare, and finance—has created new employment opportunities, increasing labor incomes and broadening consumption demand. Underpinning this is a regime of public policy that supports income growth. Minimum wage policies, rural development programs, and social security expansion have contributed to rising disposable incomes, even among lower-income groups.

Reduced Income Inequality and the Declining GINI Coefficient

A notable and under-appreciated aspect of China’s recent development is the reduction in income inequality, as reflected in its declining GINI coefficient over the past 15 years. China’s GINI coefficient peaked at around 0.49 in the mid-2000s but has steadily declined to below 0.46 in recent years - a significant improvement by global standards. The decline reflects targeted policy measures, including higher minimum wages, rural revitalisation programs, and efforts to expand social services. The narrowing gap between urban and rural incomes has been one of the biggest drivers of reduced inequality.

Income distribution plays a crucial role in shaping aggregate demand and economic stability. China’s reduction in inequality has had two critical effects. Firstly, a broader consumer base for domestic demand: As lower-income households experience faster income growth, their marginal propensity to consume is higher than that of wealthier households. This means that a larger share of GDP is now being driven by household consumption, making growth more self-sustaining. Secondly, lower regional imbalances and Higher Stability: By reducing income disparities between urban and rural areas, China has ensured that economic growth does not remain concentrated in a few major cities but is instead spread across multiple regions. This contributes to more resilient and diversified economic expansion.

In contrast to mainstream critiques that household consumption is suppressed, the reality is that rising wages, reduced inequality, and targeted government policies have expanded the middle class and increased overall consumption capacity.

Spatial Expansion of Consumption: Growth Beyond Major Cities

Another overlooked aspect of China’s growth model is the broadening of consumption demand beyond Tier 1 cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. The spatial dimension is evidenced by the ongoing processes of urbanisation and infrastructure development in so-called lower tier cities. High-speed rail, highways, and digital infrastructure investments have connected smaller cities and rural areas to economic centers, improving job opportunities and income levels. Improved transport networks reduce the cost of goods and services, making consumption more affordable even in lower-tier cities.

As a result, China has experienced rising rural and small city incomes. Government efforts to increase rural incomes through agricultural modernisation, social welfare expansion, and rural industrialisation have raised disposable income levels in these areas. The gap between rural and urban wages has been narrowing, allowing consumption patterns to converge. Digitalisation is also helping to bridge the gap between rural and urban populations, particularly via the expansion of e-commerce and digital payment. Platforms like Alibaba, JD.com, and Pinduoduo have enabled households in smaller cities and rural areas to access a much broader variety of consumer goods. Mobile payment adoption has facilitated financial inclusion, increasing both purchasing power and access to financial services.

The expansion of middle-class consumption beyond the coastal megacities means that China’s growth is becoming more geographically balanced. This reduces over-reliance on a few economic hubs, creating a more durable and broad-based domestic demand engine.

The Demographic Transformation of the Middle Class

Another major trend shaping China’s future growth model is the increasingly younger and more geographically dispersed nature of middle-class households. This matters because younger consumers have higher consumption propensities. Compared to older generations, younger households—especially those in urban areas—are more willing to spend on services, leisure, and technology. This is reflected in booming markets for domestic tourism, education, high-end consumer goods, and online services. Furthermore, expanded access to mortgage financing and financial services has enabled younger families to accumulate wealth, supporting higher consumption levels. As younger households move into higher-income brackets, their spending preferences shape new growth areas such as healthcare, digital services, green technology, and premium goods.

So, what’s the big picture? Firstly, consumption growth is now driven by both higher aggregate incomes and lower inequality. The expansion of consumption beyond megacities ensures more balanced regional growth. A younger, more financially included middle class will sustain long-term demand for new industries and services. These dynamics disprove mainstream arguments that China’s model suppresses consumption and instead show that China’s investment-driven approach has systematically enabled higher living standards and more inclusive economic growth. Far from being unsustainable, this model is structurally evolving toward a more self-sufficient, innovation-led, and demand-driven economy.

The Big Push in Energy Efficiency and EROEI Improvements

One of the most critical factors shaping China’s future growth model is the massive investment in energy efficiency and improving the Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROEI). This has profound implications for maintaining high growth without triggering inflation. Improvements to EROEI can supercharge growth because higher energy efficiency means that more output can be generated with lower energy input costs. Lower energy costs reduce production expenses, allowing firms to maintain competitive pricing while expanding output. Renewable energy investment and smart grid technologies ensure long-term energy security and price stability. State-driven investment in nuclear, solar, and wind power enhances energy sustainability and reduces reliance on fossil fuel imports.

Improving the EROEI is pivotal for several reasons. Firstly, it can amplify output with energy efficiency gains. As the ratio of energy output to energy input improves (i.e., reducing the energy cost of creating more energy), it means that less energy is required to produce the same or greater output. This allows for a multiplier effect: With more energy available for productive uses (after covering the energy costs of production), investment can expand in energy-intensive industries, such as manufacturing, infrastructure, and technology. China's emphasis on developing renewable energy sources (solar, wind, and hydroelectric power) and improving energy efficiency through advanced technologies (such as smart grids and energy-efficient industrial processes) supports this dynamic, ensuring that more of the energy produced can be reinvested into further economic development.

Secondly, it lowers the cost of energy production. By improving energy efficiency (reducing the energy input required to produce energy), China can increase its energy supply while controlling costs, which directly benefits industrial production and economic expansion. This is crucial because energy is a fundamental input for most sectors, particularly manufacturing and heavy industry, which form the backbone of China’s economic growth. In addition to making more energy available for productive activities, lower energy production costs (due to better energy efficiency) reduce the overall cost structure of the economy. This creates room for higher investment and consumption, since businesses and households have more disposable income (due to lower energy costs). It also allows for higher profit margins, which can be reinvested into further industrial growth or infrastructure development.

The improvement in energy efficiency feeds back into the economy in a positive feedback loop. As energy costs fall, more investment into industrial capacity and infrastructure is enabled. This increases economic output, which generates more income. Higher income leads to greater savings (as the economy grows) and more investment, which is reinvested into expanding energy production or improving energy efficiency. This drives further capacity growth and productivity improvements across the economy.

Improving the energy return ratio is essential for the long-term sustainability of economic growth, as it reduces the vulnerability of the economy to energy price shocks and resource depletion. China’s investments in renewable energy and energy efficiency technologies can sustain high growth rates without running into the resource constraints or energy shortages that could stifle further development. Reducing energy costs while increasing energy availability creates the kind of virtuous circle that enables continuous investment expansion and higher living standards, ultimately preventing energy bottlenecks from limiting the capacity to grow.

Pulling Threads Together

Let’s try to pull some threads together. The picture painted above is that China’s economic growth involves a number of key features:

Investment-led demand expansion.

Consumption induced by rising real incomes.

High savings rates sustained by strong investment absorption.

Price stability through capacity expansion outpacing consumption growth.

A mix of state-led and profit-driven investment incentives.

Interestingly, China’s investment-driven expansion avoided stagnation because investment acted as a persistent autonomous demand source, preventing demand shortfalls despite high savings. Price stability and real wage growth sustained consumption, ensuring that high savings did not suppress aggregate demand. Profitability mattered but was reinforced by state coordination, ensuring that overcapacity crises were mitigated by long-term investment planning.

Stable Growth Path Possible

A stable growth path through demand-driven investment is arguably possible. If this is the case, it is because investment responds to demand expectations rather than any rigid capital-output ratios. Investment=driven capacity expansion outpaces consumption growth, which leads to rising real incomes, and due to price stability, a stable or moderately rising savings rate. If consumption grows as a function of investment (but at a slightly lower rate), the economy maintains a stable accumulation path with moderate savings growth. Price stability results from supply expansion matching demand growth, coupled with intensely competitive markets, preventing inflationary overheating.

The broad ‘mental model’ explains China’s investment-led growth, where infrastructure and industrial investment drove employment growth and real income expansion, stabilising savings rates. Incidentally, itt also explains why many East Asian economies maintained high savings rates despite rising incomes—as investment expands output faster than consumption, downward price pressures sustain affordability, keeping savings rates steady.

Unlike demand-constrained models where insufficient consumption demand leads to stagnation, the Chinese experience shows that investment and capacity expansion adjust endogenously to effective demand. If firms expect future demand growth, they continue to invest despite temporarily lower profit margins. This explains why China and other high-investment economies did not suffer from chronic overproduction crises—investment expectations remained strong due to government coordination and forward-looking demand policies (e.g., urbanisation, infrastructure projects). The framework also explains how China avoided demand stagnation despite high savings rates—investment-led expansion induced consumption while maintaining price stability. The China model also clarifies why inflation did not spiral in investment-driven economies: because capacity growth kept supply expanding faster than consumption, preventing cost-push inflation.

In China’s experience, high savings do not depress demand, because investment drives household income growth, sustaining consumption, where savings are a residual. Capacity expansion prevents inflation while keeping supply aligned with demand, avoiding deflationary oversupply. Investment expectations remain strong due to urbanisation, technological upgrading, and industrial policy, preventing demand shortfalls. Government coordination and policy banks provide demand certainty, anchoring long-term investment and avoiding deflationary spirals.

What China’s experience points to is how investment sustains growth by driving wages and consumption without overheating prices, while highlighting autonomous demand as the long-run driver, with capacity adjustment preventing inflation and allowing stable savings rates. So, let’s summarise. China’s experience shows:

An investment-driven economy with high savings rates sustains growth via price stability, allowing households to meet consumption needs without reducing savings.

Falling or stable prices increase real wages, meaning consumption rises without excessive inflationary pressures.

Long-term growth stability emerges from the interaction between investment expectations, demand expansion, and endogenous capacity adjustments.

Western analysts who predict inevitable overcapacity and deflation in China misunderstand the role of investment-driven demand creation. They also misunderstand the nature of disinflation / deflation. Where deflation takes place as a result of a collapse in aggregate demand, then it is fair to say that we have a case of ‘bad’ deflation. However, not all deflation are the same, for the core reason that deflation could just as readily emerge in conditions where both demand and supply are expanding, but that in conditions of hyper-competitive markets, there is enormous downward pressure on prices. Expanded capacity is taking place in an environment where much of the expansion is also absorbed domestically. We see this in sectors as new energy vehicles where output has been growing along with the capacity of the domestic economy to absorb this expanded capacity. This does not point to a case of so-called over-capacity, but to a situation of ‘pricing people in’ through productive abundance.

Furthermore, those analysts who persist in calling for increased consumption share at the expense of investment may, actually, inadvertently be advocating policies that would lead to slower consumption growth. In China’s economic model, both investment and consumption grow together, but their relative growth rates and shares in GDP shift over time. A key misunderstanding in mainstream analysis is the assumption that a rising consumption share necessarily means faster consumption growth, while a high investment share implies over-investment and weak household demand. However, a rising consumption share at the expense of investment can paradoxically lead to slower consumption growth. Increasing the share of consumption in GDP by reducing the investment share can actually lead to slower consumption growth over time for three key reasons.

Firstly, investment actually lays the foundations for future consumption growth. A higher investment share means higher productivity growth, which enables higher wages and household incomes in the long run. If investment is reduced, productivity growth slows, limiting future wage growth and therefore future consumption growth. Secondly, consumption share of GDP can actually rise even if consumption growth slows. A rising consumption share in GDP does not necessarily mean stronger consumption growth—it can simply mean investment is growing more slowly. If investment declines significantly, even if consumption keeps growing, its rate of growth will decelerate over time due to weaker income effects. For instance, if investment slows from 8% to 2% per year, and consumption keeps growing at 5% per year, the consumption share will rise, but the total GDP growth rate will slow, reducing overall income and consumption potential in the long run. Thirdly, reduced investment can create bottlenecks that hamper consumption. If public investment in infrastructure (e.g., transport, housing, energy) slows, household costs for housing and commuting rise, reducing real disposable income. If industrial investment slows, productivity growth weakens, leading to weaker wage growth and lower real consumption expansion.

China’s experience also indicates that not all investments have the same effect on consumption. The composition of investment matters greatly. Infrastructure investment lowers household costs and increases real consumption. Public investments in housing, transport, and energy reduce household expenses, allowing a higher share of income to go toward discretionary spending. For example, affordable public transportation and energy infrastructure allow households to spend more on services, retail, and leisure rather than on basic necessities. Secondly, the upgrading of industry (via new productive forces of production, for instance), support higher wages growth. Investment in high-value sectors (e.g., automation, AI, renewables, semiconductors) improves productivity, raising wages over time. Without this, China would face a slowdown in income growth, leading to weaker consumption expansion in the long run. And, thirdly, as implied earlier, investment in energy efficiency is a significant boost to purchasing power. improvements in energy return on energy invested (EROEI) ensure that energy costs remain low, preventing energy-driven inflation that could erode household purchasing power.

The takeaway from China’s experience is that a simple shift from investment to consumption could well be counterproductive and undermine the key drivers of overall welfare growth across the society at large, and impair the ongoing productivity gains that are underpinning real wages growth. Sustaining investment in high-productivity and cost-reducing sectors that enhance future consumption potential is a more sensible way of framing priorities than the mainstream narrative about consumption over investment. Investment and consumption are not in conflict. Whereas the mainstream narrative implies that they represent a zero-sum choice, the China experience and the theoretical frames of this discussion suggest that they actually grow together. Investment-driven income growth fuels expanded consumption rather than suppresses it. A healthy rate of investment ensures continued wage and employment growth, undergirding long-term consumption.

Thanks to Professor Yan Liang for comments on an earlier draft. All errors and omissions are mine.