Behind the Potemkin facade: an emperor denuded

A Hypothecation Hypothesis and the Sublimation of Fictitious Capital via Fictitious Capital

Snapshot: This essay describes three things: (1) the expansion and erosion of American fictitious capital, as a consequence of the changing contours of global trade; (2) the creation of a parallel financial architecture from within the decaying womb of the present system, through the mechanisms of hypothecation in which USD-denominated assets, such as Treasuries, have been pledged to underwrite the creation of non-USD value flows and systems; and (3) the resultant emergence of a world in which the USD is no longer the systemic backbone, and where the real economy of use values reasserts itself. Transformations in the contours of global trade underpin the hollowing out of American fictitious capital’s utility. When the system of merchandise trade changes, the system of fictitious capital eventually changes as well. These dynamics speak to a decentering of the US economy while the Potemkin facade of USD centricity was maintained.

In Hans Christian Andersen’s folk story The Emperor’s New Clothes, the conceit and vanity of the emperor was only exposed when children didn’t understand the shared ruse, and called out the nudity. If this parable tells us something about the contemporary state of global financial systems, there is a twist. In our current situation, it’s the emperor himself who has inadvertently exposed the ruse, while almost everyone else was willing to continue pretending otherwise.

If one cannot exchange the US dollar for much that is useful, then it’s not that useful itself. And if that’s the case, the value proposition for financialised claims on future value denominated in USD - what can be called fictitious capital - also diminishes.

Hyman Minsky once observed that anyone can create their own money; the challenge is to get others to accept it. The acceptability of the US dollar has, perhaps, reached this inflection point where its utility as a medium of exchange and means of payment at an inter-national level is being seriously questioned. The fundamental driver of utility is the extent to which a medium of exchange and means of payment can be exchanged for use values needed in economic and social processes. Decades of evolution of global trading contours have fundamentally transformed the use value flow context, to a point where a global systemic surfeit of US dollars is now a sign of limited utility, rather than a proof of valued ubiquity.

Debates about dedollarisation revolve around questions of the status of the US dollar as a global reserve. To fulfill this role, the dollar acts as a unit of account; but more critically, it must fulfill the function of means of payment for ‘use values’ writ large. Ostensibly, the proportionate dominance of US dollars in central bank reserves, and the ubiquity of US dollars in global financial / capital markets, is posited as evidence of the ongoing reserve status of the US dollar. This essay questions the narrative or interpretative claims of these points of evidence; rather, I suggest that they both evidence the conditions for the decline of the US dollar as a universal means of payment.

At the heart of this argument is the proposition that the rate and extent of mainly USD-denominated fictitious capital (over-)accumulation over the past thirty to forty years has resulted in a growing detachment of monetary valorisation from the valorisation of the real economy. Further, this separation of the capital from the processes of valorisation through real production has been amplified by the return to use value to the centre of economic and social development calculus that is evident in the development of China and its own approach to the role of finance in the development of the economic system. (See my recent essay on interpreting the Chinese economic development model for more details.)

My second argument is somewhat more conjectural. It suggests that while the USD has retained what appears to be a dominant or near-hegemonic position when one considers the outsized role of the USD in global capital markets in particular, this is more a question of form over function. My suggestion or hypothesis is that within the womb of a USD dominated superstructure has emerged an alternative value flows network, which has in effect leveraged USD-denominated fictitious capital to transfer value to new value creation and flow circuits. This has taken place not through the large scale disposal of USDs or USD-denominated fictitious capital assets (by China in particular, which by virtue of its longstanding trade surplus with the US has accumulated substantial USD reserves), but by the hypothecation of these assets as collateral for new capital formation denominated in the RMB. Hypothecation is the pledging of an asset as collateral for a loan, without transferring the property’s title to the lender.

My third and final argument draws these two threads together. I suggest that the relative demise of the USD in functional relevance to the global economy of valorisation through real production will result in the progressive impairment of USD-denominated circuits of fictitious capital valorisation. The liquidity that comes from the progressive detachment of money capital and fictitious capital from real production renders these instruments as little more than phantasmagoric expressions of value-less fetishisms. As such, as non-USD circuits of real use value creation and circulation expand at a global scale, the value-in-potentia of USD-denominated fictitious capital will be stranded. Valorisation in real production asserts itself in the last instance.

This has broadranging implications, which I do not go into here. This essay is long enough as it is. But, it does have ramifications for the future role of institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF, which are both likely to be vectors of intensified geopolitical struggle over the next few years. It will also have ramifications for American living standards. A decentred dollar reduces the ability of the US to secure sufficient goods at competitive prices necessary for its households and enterprises. A painful adjustment period is thus provoked, most likely resulting in a high cost structure. I discuss this in my essay To Be Like Water.

Conceptual Underpinnings

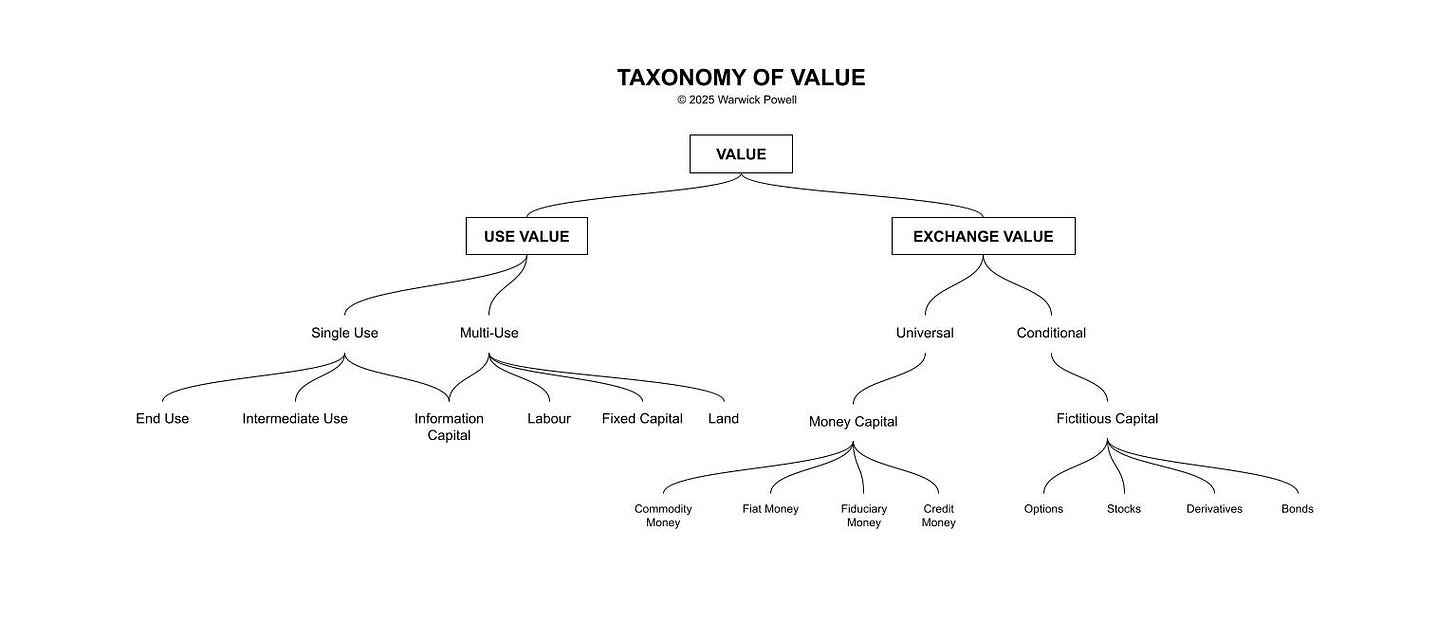

These opening passages have already introduced a number of key concepts, which require explanation. These are central to the structure of the argument, and indeed, the argument is grounded on how these concepts are articulated to provide an insight into the dynamics of capital accumulation. Capital accumulation assumes different forms, by way of processes of value in motion. Value takes two broad forms, and capitals are the embodiment of these forms in processes of production and circulation.

The key concepts are:

Use Value: Represents tangible and intangible goods and services that fulfill human needs and productive purposes. These relate to what can be called the real economy. Note, however, that ‘real’ is not reducible to tangible commodities, but also encompasses intangible services. Use values can be of a single use in nature, or can be re-used on multiple occasions over time.

Exchange Value (Ubiquitous): A medium of exchange that can be exchanged for anything which lacks intrinsic use value but enables transactions. Money capital is the quintessential ubiquitous exchange value. Money capital itself can take a number of forms, including commodity money, credit money, fiduciary money and fiat money.

Exchange Value (Conditional): Includes fictitious capital, such as legal rights that confer claims on future value flows, which function as exchange values under specific conditions. Like money capital, fictitious capital has no intrinsic use value. Their value derives from their claims on future value forms.

Fixed Capital: Physical assets such as buildings, factories, and machines, which contribute to the production process. Fixed capital could be said to be a kind of multi-use use value.

Rate of Circulation: The duration of time required by which money capital is injected into processes and transforms to generate a surplus of money capital later. A completed circuit sees money capital return to its money capital form.

There are a few other concepts that have been part of my thinking and writings, though they don’t make much of an appearance in this piece. Here the are for convenience:

Energy Capital: The necessary component to mobilise labor and machines, encompassing both human energy (from nutrition) and external energy sources (electricity, fuel, etc.). Energy capital is a type of single use ‘use value’. Real economic processes are at root energy mobilisation and transformation processes. The importance of energy was touched on in a previous essay on the Chinese economic model, and the growing focus on increasing the return of energy on energy invested.

Information Capital: The knowledge and data required to enable production and exchange. Economic activities presume sufficient information availability for actors to make informed decisions about procurement, production, sales, and purchases. Information integrity is crucial to the rate of circulation, as unreliable information slows down production, exchange, and consumption processes. In the discussion below, I leave aside the role of information capital. For those who are interested in this, my book on ‘blockchains with Chinese characteristics’ - China, Trust and Digital Supply Chains. Dynamics of a Zero Trust World (Routledge 2023) goes into the issues in detail.

Labour: Labour is the time and effort of human beings that is committed to a process of production. All labour requires energy to mobilise, by way of food and water, for example.

The figure below depicts the broad ‘taxonomy of value’ that conceptually underpins the discussion.

Use value, in this framework, serves as an abstraction that represents the tangible and intangible goods and services that fulfill human needs and productive purposes. In a complex division of labor, the necessity arises for these use values to be exchanged, either for direct consumption as end consumer goods or for further transformation as intermediate goods in downstream production processes. To facilitate this exchange, economic actors employ an exchange value that enables transactions to take place.

An exchange value must serve two primary functions: it must be a unit of account, allowing for the tabulation of equivalents in trade, and it must be a medium of exchange. The most ubiquitous form of exchange value is money, which lacks intrinsic use value as defined here. Money functions purely as an intermediary that can be exchanged for other value forms. In addition to money, other exchange values include (a) other currencies and (b) fictitious capital, that is legal rights that confer claims on future value flows.

The fundamental asymmetry in this system arises from the fact that the production and circulation of use values take time, whereas the trading of exchange values can occur instantaneously. We can see this in the three circuits depicted in the figure above. All circuits begin with the commitment of money capital, either by way of new money (fiat / credit) or from retained surpluses garnered from previous circulations.

In Circuit 1, money capital is deployed to purchase various use values (C) necessary for production processes to be activated (P). Through production, a new use value is produced that can then be sold in exchange for money capital. In the figure, Circuit 1 consumes eight Time durations. In Circuit 2, money capital is exchanged directly for another money capital (that is, foreign exchange). The trading of money capital on foreign exchange markets enables the realisation of monetised surpluses (losses). This circuit of money capital surpluses (losses) does not involve any production process directly, and can be completed on multiple occasions within a definite time period. In Circuit 3, money capital is deployed in exchange for fictitious capital, which enables either (a) access to future monetised value flows eg., dividends, interest, revenues such as rents, or (b) the exchange for (i) other exchange values (including money capital) by way of fictitious capital markets, or (i) use values at some point in the future (eg., exercise of an option over land or fixed capital). Like Circuit 2, the circulation of value in Circuit 3 can take place at a velocity far greater than is the case in Circuit 1.

As proceeds from real economic activities (Circuit 1) accumulate in the form of money capital, there is an inherent tendency for these funds to be diverted into exchange value-to-exchange value transactions (Circuits 2 or 3). These transactions, such as currency trading and financial speculation, enable the extraction of monetised surpluses without directly contributing to new use value creation. By definition, these activities are zero-sum, as they merely redistribute existing wealth rather than generate new productive output.

Consequently, the profits derived from real economic activity today effectively represent claims on the new money injected into the economic system yesterday. This dynamic shapes the broader trajectory of economic circulation, influencing the allocation of resources, the stability of financial systems, and the overall sustainability of economic growth.

Capital accumulation, whether in the form of money capital as exchange value, fictitious capital as exchange value, or fixed capital as real economy assets, can only take place through the endogenous expansion of the money supply. This expansion occurs through two primary mechanisms: (a) public fiat and (b) commercial credit issuance (fiduciary money). Public fiat involves the appropriation of new money via government spending, authorised through congressional or parliamentary processes. This method directly injects new purchasing power into the economy, funding public sector projects, infrastructure, and welfare programs. The second mechanism, commercial credit issuance, operates through credit-issuing institutions such as banks, which create new money in the form of loans extended to enterprises, organisations of various types and individuals. This credit expansion fuels both investment in productive assets and speculative financial activities, reinforcing the dual nature of economic accumulation. The necessity of continuous monetary expansion highlights the dependency of capital accumulation on liquidity injections, shaping the cyclical nature of economic booms and crises.

So long as credit creation and its channeling remain principally in the hands of private credit-issuing commercial banks, and given that the circulation and time required for the completion of each circuit varies, the provision of credit is likely to be disproportionately channeled into financial (M-M) and fictitious capital (M-F-M) markets rather than the real economics of M-C-P-C-M. This tendency arises because financial markets offer faster returns and (arguably) lower risk compared to investments in real productive activities, which require longer-term commitments of capital and labour.

On the other hand, if the ability to issue credit were held by public institutions and credit were channeled based on policy prioritisation, it would be possible to contain the expansion of the M-M and M-F-M circuits as a proportion of the economy as a whole. This, in turn, would limit the extent to which entities involved in these circuits come to dominate economic priorities. By directing credit toward productive investments in infrastructure, industry, and technology, rather than speculative financial instruments, publicly managed credit issuance could support sustainable economic development, promote full employment, and stabilize economic cycles. We will have cause to return to this later, as this goes to the heart of the mechanisms of hypothecation whereby the fictitious capital of the USD-denominated forms are held as security, enabling the creation of new fiduciary and fictitious capital forms denominated in RMB.

The expansion and erosion of American fictitious capital

The ostensible rationale for the reciprocal tariffs is the long-running trade deficit of the U.S. and the desire to rejuvenate American manufacturing. The flip-side of this deficit is that the rest of the world has been willing to accept U.S.-issued IOUs in exchange for goods and services of real economic use value. Formally speaking, these IOUs come firstly in the form of U.S. dollars (money capital), received in exchange for use values exported from enterprises in other countries. Having been received, and converted by the counterpart central bank into local currency deposits in enterprise accounts, these IOUs are then largely held by the central banks. They are held either as money deposits, or are exchanged for one form of security or another - namely, they enter Circuits 2 and 3. Typically, USDs are cycled into USD-denominated Treasuries (government-issued bonds), stocks or other financial derivatives. This is, recall, collectively what we can call the markets of fictitious capital.

The market capitalisation value of US publicly listed companies was on 4 April 2025 about $52 trillion (down $10 trillion from 2 April). At the end of 2018, the market capitalisation value was $13.45 trillion. As of 2025, the US equities market value was equivalent to about 48% of the USD value of all global publicly traded equities.

The total value of outstanding US Treasury debt, held by both the public and the government, was approximately $38.9 trillion as of April 17, 2025. The market for US Treasury debt securities averages around $900 billion per day, and rising as high as $1.5 trillion. According to a recent note from Brookings, there are approximately $4 trillion in Treasury repurchase agreement financing daily (repo’s), with average trading volume in US Treasury futures of $645 billion in notional in 2023 and higher in 2024.

According to the Bank of International Settlements, the outstanding interest rate and FX derivatives (notional amounts) increased by 17% and 12% during the first half of 2023 to reach $574 trillion and $120 trillion, respectively, totalling some $694 trillion.

The traded volumes of markets for USD-denominated fictitious capital could be in excess of $1,000 trillion annually. This tradability delivers to fictitious capital its full power; namely, its liquidity. A tradeable instrument is both a legal right to access value flows and an exchange value that can be converted into money capital at one’s will, at a monetised price that corresponds to the financial community’s self-referential estimate of expected future returns.

The total value of fictitious capital trading dwarfs the annual value of trade in goods and services of an estimated $31 trillion. The US contributes about 14% of this trade, or about $4.34 trillion. The real economy of value creation captured by way of cross-border trade is around 3.1% of the traded volume of USD denominated fictitious capital. The disparity between the sheer scale of the fictitious capital market and that of the real economy of cross border trade settlements means that whatever liquidity is available in the former can never be materialised as liquidity of conversion to use value in the latter. Put plainly, over the course of the last three or so decades, the quantity of value validated in anticipation of the future valorisation processes of the real economy - that is, the expansion of fictitious capital - has outstripped the growth in the quantity of real use value actually produced and exchanged.

The ever-expanding stock of USD-denominated fictitious capital has assumed proportions that are incompatible with the real use value production capabilities of economic systems.

The events of early April 2025 point to a growing cleavage between the book-value of USD-denominated fictitious capital and the world of use value exchange. Dollar devaluation, rising bond yields and plummets of the S&P 500 point to an unprecedented withdrawal from the USD and its fictitious capital derivatives, as holders sought to first liquidate their fictitious capital to money capital, and then exit their USD positions in favour of something else; anything else. These events evinced the coincidence of many agents - too many agents, in fact - trying to offload their securities at the same time, which again demonstrated the reality of the paradox of liquidity: liquidity cannot exist for all members of the community at the same time.

The spike on bond yields drew plenty of attention and commentary with speculation that it was this that ultimately spooked Trump and his team to backdrop on the ‘reciprocal tariffs’. Was China dumping bonds, or was it the Japanese? Market volumes suggest that whoever was exiting, they weren’t small players.

In any case, the damage has been done. And some lessons learned. The principal lesson is the detachment of fictitious value market valuations and the capacity of the real economy to support and realise the valorisation claims that would be made on it. If fictitious capital represents pre-emption on future real economy production, while at the same time offering holders, in theory at least, the prospect of converting them into money capital at any moment, the claims of liquidity are ultimately exposed as illusory. It is simply not possible to liquidate all of these accumulated promises at once, and when agents seek to do so, their money-denominated value today is impaired.

Bringing China into the Picture

My hypothesis is that over the past decade, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has embarked on a multi-pronged strategy to reduce systemic exposure to U.S. dollar-denominated assets without destabilising global financial markets. The PBOC is deeply cognisant of the paradox of liquidity and the ever-widening gap between the ostensible value of USD-denominated fictitious capital and the capacity of real production systems to deliver on fictitious capital’s claims. Yet, it has no explicit reason to ‘oil the market’ through rash efforts to liquidate its fictitious capital holdings. On the surface of things, over the past decade or so, China’s U.S. Treasury holdings have declined slowly, from ~$1.2 trillion to ~$759 billion; however, my suggestion is that this masks a far deeper structural transition. Through synthetic instruments, cross-currency financial diplomacy, and alternative clearing infrastructure, China is dismantling the dollar’s hegemony from the inside out.

Put plainly, the PBOC has actively pursued a strategy of non-disruptive exit from the USD-dominated system. While the PBOC seeks to increase the use of RMB globally, it does not expose itself to global capital volatility. It pursues these objectives through the issuance of so-called Panda Bonds, which are RMB-denominated bonds issued in China by foreign institutions. Panda Bonds seed offshore RMB use, while keeping flows tightly managed. Additionally, RMB bilateral swap lines have been established with over 40 countries, ensuring liquidity and settlement capabilities within a managed network. Lastly, China has embarked on a number of RMB commodity settlement trials where energy settlements in RMB or other national currencies have been undertaken with Saudi Arabia, Russia and other BRI nations.

Panda Bonds

Panda Bonds are RMB-denominated bonds issued by foreign entities within China, in China’s domestic bond market. By allowing foreign governments, corporations, and multilateral institutions to raise capital in RMB, China is creating organic offshore demand for RMB, facilitating real RMB-denominated liabilities on foreign balance sheets and advancing the role of the RMB as an international financing and settlement currency. In doing so, China is laying the foundations of a multipolar reserve system.

As a Panda Bond is issued, the issuer must access RMB (either via swaps, FX reserves, or trade settlement), engage with Chinese clearing systems, legal frameworks, and credit rating agencies and comply with regulatory norms set by Beijing. Doing so embeds the foreign issuer into the RMB-based financial and legal ecosystem. Additionally, Panda Bonds contribute to the normalisation of RMB-denominated debt instruments and encourage long-term RMB holdings in foreign institutional portfolios. It also contributes to the establishment of a yield curve and risk pricing framework for international issuers in RMB, enabling global actors to ‘feel their way’ towards a post-USD world, in which global capital markets can function without reference to USD or US law.

The Panda Bonds institutional arrangements enable Chinese regulators to effectively control capital flows, and proactively manage exchange rate risks. Additionally, Panda Bonds can be used selectively to promote strategic relationships (e.g., BRI countries, friendly corporates, multilateral banks), so as to internationalised the RMB with precision, and with modest or manageable instability risks.

The question is: if a sovereign or multilateral can raise money in RMB, use it to buy Chinese goods, settle trade via CIPS, and then repay in the same currency, why borrow in USD and clear through New York? The message is simple: you don’t need Treasuries when you can build your capital structure in China. The fundamental reason this is increasingly feasible is because of China’s central role in the production of use values at a global level. If organisations in other parts of the world seek to access these use values, they can do so directly without the intermediation of the USD or USD-anchored system.

Using USD Instruments to Create a Post-USD Platform

In addition to enabling foreign entities to issue Panda Bonds, China is also pursuing the issuance of USD-denominated bonds offshore. The issuance of USD-denominated bonds in Saudi Arabia is a recent case in point, and speaks to subtle and strategic moves to progress a non-USD centric global financial architecture.

In issuing USD-denominated bonds, China is signalling to the global financial community that it is confident in its ability to operate within the dollar-based system. It is saying that ‘we have dollar liquidity and access, and we can deploy it at will’. It is a geopolitical and institutional flex. Rather than reject the dollar, China coexists with it, demonstrating an ability to master it it while building the alternative.

When China issues a USD-denominated bond in Riyadh in late 2024, it provides dollar assets to the Saudi banking system, but these are issued by a Chinese sovereign entity. These dollar assets can be used for hedging, reserve diversification, or trade-related liquidity. Doing so inserts China into the interbank dollar liquidity stack, but on China’s terms. It could be said that these USD-denominated bonds are a form of diplomatic down-payment. China builds financial familiarity with counterparts through the issuance of the USD bonds, whereby Saudi Arabian banks and investors can participate. Doing so sees them deepen financial and diplomatic ties with China. Meanwhile, RMB usage grows incrementally in parallel.

China has little interest in a rapid exit of its UST positions, especially while it can continue to use them for other purposes. While the visible reduction in USTs is modest, the real action lies in (a) the development of non-recourse collateralisation whereby Treasuries are pledged to internal or external institutions to generate liquidity or fund outbound development, which creates distance between the nominal holding and the actual risk exposure; and (b) the securitisation of securities whereby additional layers are created via synthetic vehicles (e.g. policy bank conduits), which can be used to fund BRI infrastructure, energy, or industrial park projects, principally denominated in RMB or local currencies. Through these mechanisms, the UST holdings remain on the balance sheet of the PBOC - that is, they haven’t been sold en masse, running the risk of ‘oiling the market’ - but their economic value has been hypothecated and transferred to new circuits of use value development.

The USD is, in these dynamics, not substituted as the global reserve currency per se. What is happening instead is a gradual devolution into a multipolar, multi-currency settlement ecosystem, in which the RMB is often a key node in a broader network.

Rather than reject the USD outright, China has issued USD-denominated bonds to remain visible and ‘conformist’ to global markets. China has also deployed UST holdings to fund or underwrite global expansion projects, via China Development Bank, Silk Road Fund, and AIIB. At the same time, China has contributed to the development of BRICS Clear, and over the past decade developed and expanded the use of CIPS (China’s alternative to SWIFT), as new cross-border settlement rails. In doing so, it has contributed to the development of the infrastructure for bank-to-bank coordination outside the dollar.

The prevailing USD-dominated system is still in use, but it is being hollowed out from within. China is co-opting the liquidity and trust of USD markets to seed a new ecosystem. The transformation is fundamentally a reconnection of value with production as a reaction to the reality that the US fictitious capital stack outweighs its domestic productive base. China’s strategy involves re-anchoring value to material assets, commodities, infrastructure, and long-term productive capacity; that is, a return to use value as the basis of value. The medium term upshot of these shifts is that the ‘store of value’ status of the USD has eroded in large part through obsolescence.

Turning Fictitious Capital Against Fictitious Capital

Additional layers of financial engineering have likely been evolving, whereby the ‘security has been securitised’. In doing so, China is able to further abstract and redistribute risk. For instance, the PBOC could turn the pledged U.S. Treasuries into a securitised asset, allowing even more manoeuvrability and layered exposure. Consider for example the possibility that the PBOC holds, say, $200 billion in long-dated Treasuries. Instead of selling them or simply posting them as collateral for a loan, it places them into a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV).

The SPV then issues structured notes or bonds, which are backed by the Treasuries it holds. The notes are tranched whereby senior notes are low risk, low yield and pay first; mezzanine notes are of moderate risk with commensurate yield paying second; and an equity tranche, which are high risk delivering the highest return, but which are at the frontline in the event of losses. These tranches are sold to investors in global markets such as insurance companies, pensions, hedge funds, maybe even other central banks. By doing so, the PBOC has effectively converted what are in effect illiquid sovereign exposures into liquid money capital through the sale of securitised notes. The risk is now distributed across a wider pool of investors. It is likely that in such a structure, the PBOC retains some equity tranches or even total control over the SPV. In this model, the Treasuries are no longer ‘directly held’ by the PBOC but are indirectly referenced through the securitisation structure.

Given the abstract nature of fictitious capital, these structured notes could themselves be repo’d, swapped or used to write credit default swaps (CDS). Synthetic exposure is thus introduced into the market, creating layers upon layers of interlinked risk. In effect, what has emerged through these operations is a shadow U.S. debt market that is globally distributed, opaque, and harder to track.

Securitising the security enables the transformation of static sovereign debt into tradable, tranchable, globally distributed financial instruments. It enables the dilution of exposure, without causing market disruptions. Risk is embedded within the wider financial system, shifting it from sovereign holders to institutional investors. The flexibility this delivers for further leverage, yield enhancement or geopolitical repositioning is significant.

The hypothecation process has gone through a number of phases. The first phase (2005-2015) saw financial recycling of USD assets via mechanisms such as Dim Sum bonds utilising offshore SPVs and hypothecation. By the time of the first Trump administration and the intensification of rhetoric against China, culminating in the first trade war, it is likely that Chinese regulators and policy makers recognised a need to mitigate risks of US asset seizures and the geopolitical weaponisation of global finance. The experiences of Russia post annexation of Crimea in 2014 were being monitored closely. In response, the PBOC and CIC slowed the growth of hypothecation and began rotating into real, strategic assets. The aim was to reduce exposure to financial sanctions risks and gain greater control over global logistics, energy and technology supply chains. This second phase coincided with the ramping up of BRI RMB financing (2015-2018) before progressing into the current phase (2018-) where the focus has been on accumulating hard assets by way of commodities as well as key trade / transportation infrastructure and logistics hubs.

Dim Sum Bonds

Dim Sum bonds are RMB-denominated bonds issued offshore, mainly in Hong Kong. Dim Sum bonds were one of the first real "tests" of recycling China's foreign reserves into offshore RMB liquidity without having to touch the domestic monetary system much.The main years for Dim Sum Bonds was between 2010 and 2014, which saw growth from about 35 billion RMB in 2010 rising to over RMB 250 billion in 2014. After that, issuance volumes declined. As of 2023, the total outstanding stock of Dim Sum Bonds is in the order of 876 billion RMB (or ~$120billion).

How did they work? In short, the Bank of China (Hong Kong) issued RMB-denominated bonds (the Dim Sum Bonds) into the Hong Kong market. They were structured through offshore (Hong Kong registered) SPVs backed by the Bank’s holdings of USD-denominated assets, principally USTs. These assets remained held by the parent company on the mainland, and the Hong Kong subsidiaries used internal guarantees and pledges to issue RMB-denominated bonds safely and cheaply. Investors, comforted in the knowledge that these bonds were ‘backed’ by foreign currency reserves, took kindly to the Dim Sum bonds. This phase supported the internationalisation of the RMB and enabled the PBOC to leverage USD assets without disposing of them.

China Development Bank and BRI RMB Loans

The CDB issued a large amount of RMB-denominated loans to BRI project partners in areas such as energy projects in Central Asia and railway projects in Southeast Asia. It did so by being able to strengthen its own balance sheet by access to China’s foreign reserves pool. In many / most cases, SPVs were established for projects, which indirectly referenced China’s USD denominated assets, without direct liquidation of these assets. Credit insurance and guarantees were frequently backstopped via SAFE / CIC-linked facilities. These mechanisms meant that projects could be priced in RMB, further increasing RMB’s internationalisation. USD-denominated assets could be used as security, without needing to sell them. These assets were effectively ‘shadow pledged’.

China’s SAFE Investment Company and Offshore Asset Recycling

In this case, the SAFE Investment Company Limited (Hong Kong) took over the management of a portion of PBOC’s foreign reserves. These assets included USTs, which were used to provide security backstops for offshore RMB financing vehicles. Investment vehicles or SPVs would be established by SAFE to manage foreign assets. The SPVs benefited from the hypothecation of the underlying assets held by SAFE, which supported RMB-denominated private investments around the world. Without selling USD positions, an offshore ‘quasi sovereign’ RMB asset class was thus created. RMB liquidity globally was improved, and overseas Chineses banks’ balance sheets were simultaneously bolstered. Again, no liquidation of USD assets was required.

Triple Layered Risk Mitigation

Loans were issued to BRI JV projects were effectively secured via triple layered security: the USD reserves or UST as the backstop; any guarantees provided by the China-side JV partner parent company; and lastly the invested project vehicle’s own assets, namely what was built. Through this approach, China was able to effectively mitigate risks on what were otherwise - superficially at least - relatively high risk projects.

On paper, many BRI projects were seen as comparatively high risk. They were located in frontier markets, often exposed to considerable political instability, and the projects had little to no proven cash flow capabilities. In practices, however, such financial risks were more or less negligible for Chinese credit providers because of the availability of USD assets as backstop, which could be tapped if needed (not even sold, just re-hypothecated). Additionally, Chinese JV partners were usually required to provide headquarter-backed guarantees, and last but not least, there was the rights to the physical assets created via the JV. Refinancing in these conditions was never difficult.

Dedollarisation by Stealth

What I have described is a hypothesis, backed by some case studies, showing how sovereign exposure becomes abstracted into the global shadow banking system. At this level, the PBOC is no longer just holding U.S. debt, it is writing the meta-narrative of capital flow. We are thus seeing the gradual internal erosion of dollar hegemony, not through confrontation, but through financial re-engineering, strategic abstraction, and transactional redirection. The dollar remains the form, but not the substance.

So to recap, let’s walk through what such a process of collateral transformation looks like. Firstly, USTs are not sold en masse. Instead they are pledged, repo’d or securitised. The USD remains the nominal denomination, but economic control of value is diffused. The PBOC and others could extract liquidity and reallocate value elsewhere through such techniques, while on the face of things, the US debt pool remains ‘held’.

The proceeds of these operations are then reinvested outside the USD system via initiatives such as BRI infrastructure development, RMB-based commodity contracts, expanded acquisition of gold reserves as well as various eRMB pilots. Foreign sovereign debt in regional blocs could also acquired. The point here is that USD holdings remain ‘on the books’, but value is being actively transferred to alternate ecosystems.

From here, a push is initiated to expand the use of CIPS, China’s cross-border RMB settlements system. It’s no surprise that Chinese authorities have in the wake of Trump’s reciprocal tariffs moved to promote the greater use of RMB for cross border settlements. Additionally, bilateral and multilateral currency swap lines (e.g., BRICS Clear, ASEAN-based cross-border payments agreements and such like) are implemented, so that national currencies are used directly in trade, especially for energy, commodities, and tech components. Increasingly, settlements bypass the USD and USD system, and progressively the need for dollars at the transaction layer diminishes.

We thus enter a period in which the USD remains formally the principal global reserve asset. However, it is used less and less in trade; and less and less is held unhedged. The USD’s reserve status becomes largely symbolic. There is no ‘big bang’ reserve shift; the USD is simply rendered marginal in actual flows. Its privileged status erodes from the inside out, bypassed by changing economic value flows and new institutions.

The future of the UST: hollowed out collateral

If the collateral ceases to matter economically, then U.S. Treasuries become little more than formal, symbolic tokens in an ecosystem that no longer depends on their liquidity, yield, or credit quality. Treasuries are held on balance sheets for various reasons, including optics, the requirements of ratings agencies, IMF quotas and such like. They continue to appear as ‘safe assets’ but their functional role is principally ceremonial.

As UST value becomes increasingly ceremonial, they provide diminishing claims against future value. In this case, their value as collateral diminishes over time and their exchangeability is similarly constrained. No-one wants them as ‘base money’ or as a key component of cross-border trade settlements. Should these dynamic hasten, at some point in the not too distant future, central banks and sovereign wealth funds may still ‘hold’ Treasuries, but principally to sustain the facade of the US-dominated system. There is no need to mount a direct confrontation with the USD system if one doesn’t have to. Meanwhile, the flow of use values is conducted in national currencies.

If, and this remains a big ‘if’, an increasing number of nationals progressively behave as if Treasuries are optional, the cultural consensus that gives the USD its reserve status begins to wilt. If USTs aren’t used as collateral, are not part of the universal settlements layer as the means of payment, and consequently aren’t used as a store of exchange value, then Treasuries are just unsecured claims on a fiscal-monetary machine that no one depends on. The erosion of the USD-dominated system presupposes neither default nor inflation. Erosion simply requires marginalisation as a consequence of shifts in real use value flows. That is the ultimate danger of an uncollateralised shell: a globally acknowledged form without function.

No default but no value

In recent times, there’s been quite a lot of discussion about the impending need for the US Treasury to refinance some $9 trillion of Treasuries. Some have again spoken of the prospects of the US defaulting. In a technical sense, there is no possibility of the US federal government defaulting on debts issued in its own currency. This concern largely misses the point.

In a world where default is impossible, value has, nonetheless, left the building. A distinction between form (nominal payment in dollars) and substance (real, accepted value in trade, production, and settlement) is emerging, which defines the critical transformations that are now unfolding in the global financial and economic system.

Let us firstly recall that the US exerts financial power through instruments such as tariffs (the weaponisation of access to the US market) and sanctions (weaponisation of access to the USD clearing system and Treasury markets). Sanctions have been increasingly tried over the past decade or so, with failure increasingly evident. The latest episode of so-called reciprocal tariffs exposes the limits of US financial power. It also shows how the rest of the world is better prepared today than it has ever been.

Currency swap lines, commodity barter systems, and alternative settlement networks are in place and in use. China, Russia, Gulf nations, ASEAN, and even parts of Europe have alternative value circuits, with the US market contributing no more than about 14% of global imports, and diminishing. The reciprocal sanctions debacle doesn’t so much as collapse the multilateral global trading system but accelerates the evolution towards a more multipolar global trading and payments system.

As for the market for Treasuries, nothing prohibits the US government from issuing more Treasuries. There’s no risk of formal default; the Fed can always “print.” As Treasuries are issued and taken up, coupon payments arrive, and as the securities mature, the Principal is rolled over. Yet, in the corridors of global finance, investors, central banks, and corporates start to ask quietly: what’s the point? If dollars can be created indefinitely, then ‘payment’ becomes a tautology. There is no credit risk, but there is also no store-of-value confidence particularly when the default ‘dollar zone’ - the North American economy - does not produce anything that the world cannot get elsewhere. We may well be at at point where these quiet questions are getting louder.

Meanwhile, the real economy of use value production and circulation begins to settle in other units. We can see for instance the pricing and settlement of oil trade in RMB via the Shanghai Oil and Gas Exchange. It is likely that copper will be settled increasingly in peso-RMB contracts, and grains will be exchanged in non-USD markets via the emerging BRICS grains exchange. China operates two RMB-denominated markets for rare earths and strategic minerals. Over 90% of China-Russia trade is already settled in RMB or Rubles, and over 70% of Russia-ASEAN trade is settled in national currencies. The use of the Rupee for India-Russia settlements continues to grow, notwithstanding early challenges of Rupee liquidity. Over 50% of trade with China involving foreign companies and about 70% for Chinese companies is settled in RMB. These are not trivial.

These mechanisms reconnect use value to exchange value, diminishing the role of USD-denominated fictitious capital. Meanwhile, the USD persists but its role is largely a formality and a function of historic volume legacy.

Treasuries don’t default. But they run the risk of yielding real negative returns as inflation exceeds the coupon rate. USTs and USDs are not longer used to exchange for use values outside of dollar zones, and aren’t universally accepted in settlement networks. They become a kind of ‘phantom wealth’ with a high nominal exchange value (denominated in USD) with comparatively modest real economy leverage. Treasuries increasingly become zombie assets, with little meaningful economic value. With the passage of time, sovereign and institutional actors redefine value in their own ecosystems. Reserves become diversified baskets tied to trade exposure. Settlement systems align with production and consumption circulation networks, rather than by the dictates of financial hegemonies. And, fiat money creation becomes tied more directly to energy, resource flows, and productive output. Digitalisation of supply chains enables this linkage to be better addressed.

The formal mechanisms of the dollar system, Treasuries, Fed payments, Wall Street clearinghouses, still exist. But, outside of the United States, they are increasingly ceremonial instruments in a world that has migrated to a new logic of value. There is no financial revolution; there is no collapse of the USD system. What seems to be unfolding is just a quiet, irreversible detachment of form from substance.

Strategic Patience, Structural Shift

We have been witness to a medium term strategy by the PBOC to dilute its exposure to US dollars and USD denominated financial assets without ‘oiling the market’. On the face of things, therefore, PBOC holdings of USTs has been falling but only gradually from about $1.2 trillion a decade or so ago to about $759 billion today. None of this has been enough to rock the market. At some point, UST holdings may become stranded assets, but their ‘value’ has already been hypothecated into non-USD value flow circuits.

At the same time, the PBOC has been (1) collateralising USTs by way of non-recourse loans, some of which will be via the securitisation of securities to create more ‘distance’ and spread the risk institutionally, to transfer value from the USTs into funds that are used to develop the BRI etc.; (2) issuing Dim Sum and Panda bonds to slowly seed the idea of China as a stable global financier and gradually grow liquidity, without having to open its capital accounts; (3) issuing US dollar denominated bonds; and (4) building alternative payment platforms and inter-bank messaging systems. In other words, a new system is being born from within the old USD-dominated system, without creating major disturbances on the surface. But in reality, just as the US economy’s share in real productive capacity is diminishing in global relative terms, the very foundations of US dollar denominated global financial system are being stripped away.

What emerges is not a simple ‘replacement’ of the USD by another hegemon, but a pluralist structure, in which national currencies dominate domestic and regional flows. In this new paradigm, a supra-national trade settlement architecture (like BRICS Clear or a commodity-linked numeraire) intermediates large-scale interbank transactions. In this setup, the USD is no longer the systemic backbone, but becomes just another asset. The post-dollar world will be less hierarchical, more plural, and more anchored in productive capacity rather than liquidity illusions.

China (and its partners in the Global South) is engineering a quiet revolution. It seeks not confrontation and certainly has not pursued anything that could be said to be a sudden rupture. Rather, it has pursued a non-disruptive disintermediation of the dollar system. By using the old system’s tools to build the new, China has bought time, avoided panic, and steadily transferred capital, trust, and institutional coordination into a new model. King dollar is not being dethroned; it is being sidestepped. Fictitious capital is not collapsing; it has been hypothecated and recontextualised.

And the real economy of use values is reasserting its primacy.

Great essay.

Especially appreciate how you frame hypothecation and shadow asset recycling as the real mechanism hollowing out dollar hegemony — not dramatic liquidation but quiet reengineering.

Feels like we’re witnessing a slow migration from nominal claims to real use-value flows — without the fireworks most people expect.

Don't understand much of the detail, being a biological scientist, my grasp of macro-economics is more basic than an average 2 yr old, but my understanding is that the hyper-financialisation of USD based global economy over recent decades has finally reached its long-predicted inflexion point.

Tim Morgan's surplus Energy Economics model, explains that there are 2 linked economies... The "real" economy of material tangible goods & services, and the financial economy of "mouse-click money" .. when these 2 economies diverge too much and the real-world value link between them is broken, the financial asset economy has to break and re-value down to the level of the "real" economy which in turn, is based on fundamental core energy. As the planet depletes in FF energy stores, it makes real economic sense to invest in multiple alternatives and innovate. Also makes sense that the majority of US graduates go into MBA's for Wall Street, or Law, but the majority of Chinese graduates go into STEM jobs.

Because in the end, you can't eat money, it doesn't even burn well enough to keep you warm in winter. I also deeply appreciate China's method seems to be moving slow and steady, rather than break it suddenly.

And, the Trump Dream Team's behaviour seems more of a Hail Mary pass, and we all know how they usually play out.