The Panama Canal has emerged as a focal point of growing American anxieties mixed with national mythologies, coupled with energised Chinese incredulity at Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-Shing’s brazen willingness to sell the Canal’s port concessions to US private equity giant BlackRock, in the face of pressure from the new Trump Administration. Li has been accused of unpatriotic greed, with some calling for interventions to prevent the sale.

Donald Trump has recently reignited a long-standing American myth - that the Panama Canal was built by America for America - laying the groundwork for claims that the Canal should be returned to American control, as if by ‘birth right’. In what is now a standard gambit, Trump laments that the United States has been treated unfairly in relation to the Canal, disregarding the fact that American ships pay the same fees as any other vessels transiting the passage. More provocatively, he has stoked fears that China controls the Canal’s ports, a claim designed to fuel racial and geopolitical anxieties while laying the groundwork for an American infrastructure grab.

These assertions ignore the reality that the Canal was not only the result of American imperial conquest but was ultimately returned to the people of Panama in 1999. The broader narrative serves a dual purpose: it reinforces a vision of American hegemony over the Western Hemisphere while conveniently rationalising expansionist ambitions under the guise of economic security.

Yet, despite these affective reactions, there are longer term material realities that perhaps shed a different light on the relative and declining significance of the Canal in both economic and geopolitical terms. The present-day importance of the Panama Canal to global trade is in decline, making these anxieties more about American fragility than about any real geopolitical shift. Other realities also constrain the kinds of interventions that could be contemplated in relation to Li’s sale, although there will undoubtedly be repercussions.

Trump’s Panama Canal Mythology

The Panama Canal’s origins are deeply entwined with colonialism, corporate exploitation, and geopolitical manoeuvring. Long before the French or Americans undertook its construction, the Isthmus of Panama had been a crucial corridor for imperial trade, dating back to the Spanish Empire’s use of the route to transfer Peruvian silver to Europe. The idea of a canal that could permanently link the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans was a dream of imperial strategists for centuries, but it was the late 19th and early 20th centuries that saw this vision materialise—at great human and national cost.

The first major attempt at constructing the canal was undertaken by France in the 1880s, led by Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had previously built the Suez Canal. However, the Panama project was marred by financial mismanagement, engineering miscalculations, and tropical diseases such as malaria and yellow fever, which decimated the labor force. The collapse of the French project, which bankrupted investors, provided an opportunity for another imperial power to fill the breach. In stepped the United States.

Recognising both the commercial and military advantages of controlling a transoceanic passage, the U.S. aggressively pursued the canal’s construction under President Theodore Roosevelt. However, rather than negotiating with Colombia, which controlled Panama at the time, the U.S. orchestrated Panama’s secession in 1903, backing a local independence movement in exchange for near-total control over the proposed canal zone. The resulting Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty granted the U.S. sovereign rights over a 10-mile-wide strip of land through the heart of Panama—a deal that Panamanians resented but were powerless to overturn.

Construction of the canal resumed under American control, relying on a massive, predominantly foreign workforce, including thousands of Afro-Caribbean labourers recruited from British colonies such as Barbados and Jamaica. These workers endured harsh, racially stratified conditions. White American supervisors enjoyed superior wages, housing, and healthcare, while Black and indigenous workers performed the most dangerous tasks for meagre pay. Many workers died during the Canal’s construction. The canal’s completion in 1914 cemented U.S. dominance over Panama, effectively reducing the country to a de facto colony. The U.S. maintained total jurisdiction over the Canal Zone, establishing military bases, segregated settlements, and an administration that functioned independently of Panamanian authority.

As anti-colonial and nationalist movements gained momentum globally in the mid-20th century, Panama became a focal point of resistance. Protests erupted in the 1950s and 1960s, with Panamanians demanding sovereignty over the canal and an end to American control. These tensions culminated in the 1964 "Flag Riots," where U.S. forces killed Panamanian demonstrators who had attempted to raise their national flag in the Canal Zone. The incident intensified diplomatic pressure, leading to the historic Torrijos-Carter Treaties in 1977, which set the stage for the gradual transfer of the canal to Panama, culminating in full Panamanian ownership on December 31, 1999.

Despite this formal decolonisation, the canal remains a site of geopolitical contestation. The U.S. continues to view the canal as a strategic asset, often framing its operations within a broader narrative of regional security and trade dominance. Meanwhile, China's increasing economic presence in Panama, ostensibly through investments in port infrastructure by a Hong Kong-affiliated company - Hutchison Ports - owned by tycoon Li Ka-Shing, has fuelled new anxieties in Washington, echoing old imperial concerns over control of global trade routes.

Hutchison Ports, a subsidiary of CK Hutchison Holdings, was awarded its concessions for port operations in Panama in the late 1990s. In 1997, it was awarded a 25-year concession to operate the Balboa Port (Pacific side) and Cristóbal Port (Atlantic side) at the Panama Canal. The concession was extended in 2015. Hutchison Ports is headquartered in Hong Kong, but its ultimate holding company, CK Hutchison Holdings, is registered in the Cayman Islands. It is worth noting that many of CK Hutchison’s subsidiaries are structured through offshore entities, including those in Bermuda and the British Virgin Islands.

Hutchison Port’s concessions are the basis upon which Donald Trump has claimed unacceptable Chinese control over the Canal, though given the international registrations of the operating entities, the extent of Chinese government control is in reality, circumscribed. I will return to these issues later.

That notwithstanding, Trump persisted in intensified rhetoric about Chinese influence, pressuring the Panamanian authorities and the concession holders to relinquish control. Li’s company, CK Hutchison Holdings, agreed to sell its interests in its global ports network, including the Panama Canal ports to a consortium led by BlackRock, in a deal valued at approximately $22.8 billion. This transaction has attracted significant attention due to the amplified political and strategic context, with emerging pressure from some Hong Kong figures being directed at Li to pull out of the deal.

The Canal’s Structural Constraints and Declining Importance

For Trump and for critics of Li, the Canal has considerable economic and geopolitical importance. That said, whatever its historic significance, current realities within a wider context and ongoing trends in global trade, regional infrastructure development and the progressive evolution of global digital payment systems all suggest that the Canal is structurally constrained and is of declining importance. Perhaps this explains, in part at least, the hasty willingness of Li to offload the concessions; he could see the commercial writing on the wall.

The Panama Canal, once a critical artery for global trade, faces a decline in strategic importance due to a confluence of environmental, economic, and geopolitical factors. Climate change, particularly prolonged drought conditions, has severely hampered its operational capacity. The Canal’s lock system relies on freshwater from nearby lakes, and with decreasing rainfall, authorities have been forced to impose unprecedented transit restrictions. In late 2023 and early 2024, these restrictions reduced daily transits, causing severe shipping delays (of up to three weeks) and increased costs for global supply chains.

Despite the 2016 expansion, which added a third set of locks to accommodate larger ships, the canal continues to experience congestion. The Panama Canal’s expanded locks (known as the Neopanamax locks) can handle ships up to 14,000 TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units) at maximum capacity. Aside from the environmental constraints, increasing global trade volumes and larger vessel sizes mean that many modern mega-container ships (Ultra Large Container Vessels, ULCVs) with capacities of between 18,000-24,000 TEU cannot pass through the canal, limiting its utility for global shipping. These vessels are too wide and too deep to pass through the Canal.

Ultra Large Container Vessels are becoming the workhorses of global trade, especially between Asia and Latin America. The need for deeper water and wider channels means that even future expansions would not resolve this issue without massive engineering overhauls (which are unlikely due to water shortages). ULCVs provide economies of scale, meaning lower costs per container compared to smaller vessels that can transit the Panama Canal. Fuel efficiency per container is much higher in ULCVs, making them the preferred choice for long-haul routes like China-Brazil and China-Peru. Shipping companies prioritise cost savings, and avoiding the canal’s fees and congestion further incentivises ULCV-based routes.

Beyond environmental concerns, the Panama Canal's diminished relevance is also a function of shifting global trade patterns. The rise of alternative trade routes, the expansion of transpacific shipping lanes, and the strengthening of direct trade between Asia and Latin America have eroded the Canal's once-dominant position. While the United States remains a significant user, its reliance on the canal is more pronounced than that of global markets at large.

The Rise of Chancay Port, Digital Currencies, and China's Expanding Role

One of the most consequential developments undermining the Canal’s importance is the construction of the Chancay Port in Peru. Financed with significant Chinese investment, Chancay is poised to become a major transpacific hub, directly linking South America to Asian markets without the need for Panama Canal transit.

Chancay is designed to handle ultra-large container ships that the Panama Canal cannot accommodate, and plans are underway to develop extensive east-west transport infrastructure that will connect the port to Latin America’s interior and its Atlantic-facing economies, such as Brazil and Argentina. This development represents a profound shift in global trade dynamics: rather than routing goods through American-dominated maritime corridors, Latin American countries will have a direct alternative that strengthens economic ties with China and other Asian economies. It is worth noting that Brazil’s Santos Port and Argentina’s Buenos Aires terminals are also expanding their capabilities to accommodate ULCVs.

This shift dovetails with broader trends in global commerce, including the increasing role of BRICS countries and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The emergence of digital currencies across Latin America and Asia is reinforcing these shifts, allowing cross-border trade and financial transactions to bypass the U.S.-dominated financial system. Countries within BRICS, including Brazil, China, and Russia, have been at the forefront of promoting digital payment systems that enable direct settlements in national currencies, reducing reliance on the U.S. dollar.

Latin America’s increasing experimentation with central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), such as Brazil’s Drex and Argentina’s proposed digital peso, aligns with China’s push for the internationalisation of the digital yuan. In recent years, the United States has intensified sanctions affecting financial and banking services in the Caribbean, particularly targeting Cuba. These measures have created economic challenges in the region. In response, Chinese financial institutions have expanded their presence to fill the void left by reduced Western engagement.

China's trade with Brazil and other East Coast South American nations has traditionally relied on the Panama Canal for maritime transport. However, the development of the Chancay Port in Peru, coupled with emerging east-west terrestrial infrastructure, is poised to reshape these trade routes. In 2023, bilateral trade between China and Brazil reached US$181.53 billion, marking a 6.1% year-on-year increase. China exported US$59.11 billion worth of goods to Brazil, while importing US$122.42 billion from Brazil. Overall trade between China and Latin America grew 26-fold from 2000 to 2020, increasing from $12 billion to $315 billion. This figure is projected to double by 2035, potentially reaching over $700 billion.

The Chancay Port, inaugurated on November 14, 2024, represents a significant Chinese investment in South America. A joint venture between COSCO Shipping Ports (60% ownership) and Peru’s Volcan Compañía Minera (40% ownership), the port is strategically positioned to enhance trade between South America and Asia.

The Chancay Port is expected to reduce shipping times from Peru to China from 35 to 23 days, cutting logistics costs by at least 20%. Upon completion, the port aims to handle up to 1.5 million TEUs annually, with plans to increase capacity to 3.5 million TEUs. The port's development includes plans to link it with inland nations and those without west coast access, potentially altering traditional trade routes that previously depended on the Panama Canal. These developments suggest a potential shift in Latin America-China trade dynamics, with the Chancay Port serving as a pivotal gateway, especially for countries on the eastern side of the continent seeking more direct access to Asian markets.

Looking forward, it seems highly likely that Brazilian exports will increasingly use Chancay given shorter transit periods overall, which will substantially reduce costs. The same applies for Chinese exports into Brazil. Given that the Chancay Port will reduce shipping times between Peru and China, Brazilian exporters are likely to find it more cost-effective to transport goods westward overland to Chancay instead of relying on Atlantic routes through the Panama Canal. The same logic applies to Chinese exports into Brazil—using Chancay and an overland connection could be faster and cheaper than the traditional Atlantic passage.

Several factors support this shift:

Transit Cost Reduction: The cost of navigating the Panama Canal has increased due to congestion and toll hikes, making alternative routes more attractive. Chancay’s efficiency and connectivity investments could reduce logistical expenses significantly.

Infrastructure Development: There are ongoing projects to strengthen east-west terrestrial logistics corridors linking Brazil, Bolivia, and Argentina to Peru’s Pacific coast. These developments will make Chancay an even more viable export hub for South America’s interior economies.

Increased Container Handling Capacity: Once fully operational, Chancay is expected to handle up to 3.5 million TEUs per year, directly challenging traditional Atlantic-based routes.

Chinese Investment in Logistics: Given China’s stake in the port and its broader Belt and Road Initiative objectives, Chinese firms are likely to further invest in transport corridors that maximise Chancay’s utility for Brazil and other Latin American nations.

If current trends hold, Chancay could become the dominant gateway for South American exports to China, bypassing traditional Atlantic routes and the Panama Canal altogether.

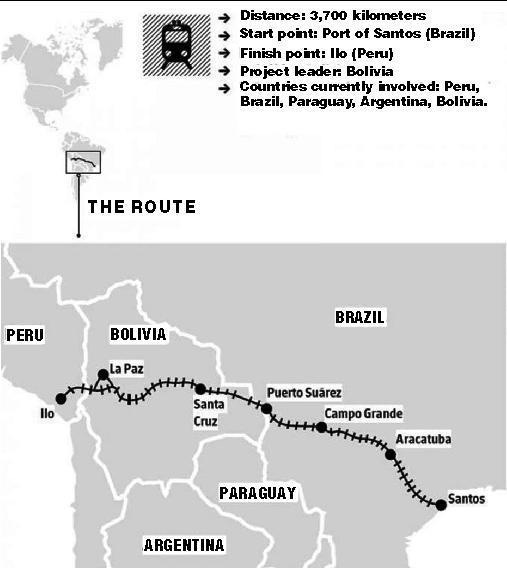

The Bi-Oceanic Railway Corridor (BORC) is a game-changer. This $15 billion mega-project aims to bypass the Panama Canal entirely by creating a direct overland rail link between Brazil’s Atlantic coast and Peru’s Pacific coast. Once operational, it will provide a faster, cheaper, and higher-capacity alternative for trade between Asia and Latin America. At a total length of approximately 3,750 km (2,330 miles), running from Santos (Brazil) to Ilo (Peru), the route crosses Brazil, Bolivia, and Peru, linking major agricultural and mining regions to the Pacific. At least 10 million tons annually, reducing shipping costs and times significantly. The BORC could cut transit times from Brazil to China by 10–14 days compared to the Panama Canal route.

The development of new transport infrastructure has important strategic implications. With congestion and rising costs at the Panama Canal, the BORC provides an overland alternative that removes dependency on a single chokepoint. Bypassing the Panama Canal becomes increasingly plausible and cost-effective. Given China’s heavy investment in South American infrastructure, the railway would align with its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), enhancing its influence over regional trade flows. In tangible terms, this will enable Brazil’s soybeans, iron ore, beef, and other commodities to move to Asian markets more efficiently, lowering costs for both exporters and Chinese buyers. Furthermore, landlocked economies would be better integrated into global trade patterns. Bolivia and Paraguay, which currently rely on the Paraná-Paraguay waterway or Atlantic ports, would gain direct access to the Pacific, reducing logistical costs and opening new trade routes.

Once operational, the BORC—combined with the Chancay Port—could eliminate the need for Latin American exporters (especially from Brazil, Argentina, and Bolivia) to send goods via the longer, more expensive Atlantic-Panama route. Instead, they could ship directly from the Pacific. If implemented successfully, the BORC will reshape global trade by creating an Asia-Latin America direct corridor, completely altering the historical reliance on the Panama Canal.

A New Financial Architecture

In addition to the development of alternative hard transportation infrastructure, the wider region of Latin America and the Caribbean are being reshaped in terms of financial infrastructure.

In response to the reduced Western financial presence, Chinese financial institutions have increased their involvement in the Caribbean. Between 2005 and 2022, China invested over $10 billion in six Caribbean countries, focusing on sectors like tourism, transportation, extractive metals, agriculture, and energy. In 2022, China’s development finance institutions issued $813 million in new loans to Latin America and the Caribbean, with a portion directed to Caribbean nations. For instance, the Export-Import Bank of China provided a $121 million concessional loan to Barbados for the Scotland District Road Rehabilitation Project and a $192 million loan to Guyana for Phase II of the East Coast Road Project.

These investments indicate China’s strategic approach to strengthening economic ties and expanding its influence in the Caribbean, especially as traditional Western financial entities reduce their engagement due to sanctions and other policy decisions.

Through its engagement with countries such as Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, and the Bahamas, China has financed major port developments, road networks, and energy projects, while also providing digital banking solutions that integrate with broader financial networks in Asia. The Bahamas, for instance, has already launched its Sand Dollar CBDC, which could potentially facilitate trade with China outside the U.S. financial system.

Several Caribbean nations have been proactive in exploring and implementing CBDCs. In October 2020, The Bahamas launched the Sand Dollar, becoming the first country globally to introduce a CBDC. In March 2021, the ECCU introduced DCash, a CBDC rolled out across member countries of the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union, including Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, and St. Lucia. The Bank of Jamaica launched its CBDC, known as Jam-Dex, aiming to enhance financial inclusion and payment efficiency.

Turning to Latin America, we also see developments in relation to national digital currencies. Both Peru and Paraguay are actively exploring the development of CBDCs. The Central Reserve Bank of Peru (BCRP) has been proactive in its CBDC initiatives. In November 2021, BCRP President Julio Velarde announced that Peru is developing a CBDC, collaborating with other central banks to issue a domestic digital currency. The BCRP has engaged with stakeholders, including the banking sector, payment service providers, and the fintech community, to assess the conditions for a successful CBDC implementation. In July 2024, the BCRP announced a CBDC pilot led by Bitel, a mobile network operator, focusing on unbanked populations and incorporating offline capabilities.

The Central Bank of Paraguay (BCP) is in the research phase regarding CBDCs. The BCP is analysing the implications of issuing a CBDC, monitoring international initiatives, and assessing potential impacts on the national payment system. While not a CBDC, the BCP introduced the ‘local currency system’ in 2018, interconnecting with the Real-Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) systems of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay, enhancing cross-border payment efficiency.

Brazil is actively advancing its CBDC, known as Drex. The Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) launched Drex by the end of 2024, positioning it as a digital representation of the existing Brazilian Real. This initiative seeks to complement physical currency, reduce operational costs, enhance financial inclusion, and bolster the security of both wholesale and retail transactions. In its second phase of experimentation, the BCB has outlined 13 development themes for Drex, collaborating with major technology and payment companies to refine the platform. Notably, the BCB is piloting a trade finance solution for Drex, focusing on the automated settlement of agricultural commodity transactions. Brazil’s initiatives will most likely align with, or be interoperable with, the emerging BRICS Clear settlements system being developed by BRICS nations. (Note that Brazil is chairing BRICS in 2025.)

Bolivia's approach to digital currencies has evolved recently. Historically, the Central Bank of Bolivia (BCB) prohibited the use of virtual currencies, stating that only currency issued by the monetary authority was legal. However, in mid-2024, the BCB lifted this blanket ban, allowing banks to handle cryptocurrency transactions, although cryptocurrencies are not recognised as legal tender. Following this policy change, Bolivia experienced a significant increase in virtual asset trading. Between July and September 2024, the country saw a 105% rise in average monthly virtual asset trading compared to the previous 18 months. Additionally, Bolivian banks have integrated support for stablecoins like USDT, providing customers with seamless access to these digital assets. In March 2025, Bolivia announced plans to utilise digital currencies for energy imports amid dollar and fuel shortages.

Taken together, these developments indicate that China is building a trade and finance-based bridgehead off America’s southeast coast in the Caribbean while simultaneously establishing a strategic foothold on the west coast of Latin America through Chancay. This two-pronged expansion erodes U.S. dominance in hemispheric trade and financial flows, enabling direct linkages between Latin America and China without Washington’s oversight. Regional digitalisation is positioning the various nations to capitalise in new cross-border payments systems that are progressively expanding, including the future BRICS Clear platform.

What’s at Stake?

We now return to ask, what’s at stake? On the one hand, we have Li’s decision to sell the concessions and the reactions that this has engendered. On the other hand, we have a wider set of questions about the evolving strategic significance of the Panama Canal within the broader context of Caribbean and Latin American development, and how these integrate within unfolding patterns of global geopolitical economic transformation. Set against this backdrop, the reclamation of the Canal’s ports by American interests seems to be of greater significance to the U.S. than anyone else. There are considerable political optics at play now.

The sale of the Panama ports is, of course, part of an omnibus transaction involving some 45 ports or terminals in 20 nations. This wider network of port infrastructure1 has not been considered in this essay, so that the observations below are limited to the situation in Panama.

Declining US Influence

In the face of declining relative commercial utility, the recent push by Donald Trump for the U.S.—via BlackRock—to take over Panama's port infrastructure appears to be driven more by imperial nostalgia and misplaced fears of Chinese influence than by an appreciation of shifting trade realities. The notion that the U.S. must intervene to prevent supposed "Chinese control" of the Canal is symptomatic of a broader geopolitical paranoia rather than a response to economic imperatives.

The U.S. fixation on "Chinese control" of strategic infrastructure often leads to reactionary moves that fail to account for larger economic shifts. While the Trump-backed push to reclaim control over Panama's ports may be framed as a strategic necessity, it is more a reflection of Washington's anxiety over its waning global dominance. Investing heavily in canal infrastructure at this stage, when climate constraints and changing trade routes are already reducing its value, is emblematic of a broader miscalculation—one that sees geopolitical contestation where economic obsolescence is the more pressing issue.

More broadly, this episode highlights Washington’s deep-seated anxieties about its declining dominance over the Western Hemisphere. Trump’s aggressive rhetoric towards Mexico, his musings about acquiring Greenland, and his recent remarks about Canada all point to an American strategic posture that seeks to reassert control over its near abroad. However, the very economic forces driving global trade—regional integration, alternative infrastructure development, and shifting trade routes—are working against this vision.

As the U.S. clings to outdated imperial myths, the world continues to evolve in ways that undermine America’s ability to dictate the terms of global commerce. The Panama Canal may remain a symbol of America’s historical colonial dominance and future ambitions, but its declining strategic importance underscores a deeper reality: the unipolar era is at an end.

To intervene or not?

CK Hutchison is incorporated in the Cayman Islands, with substantial operations in Hong Kong and mainland China. This makes direct intervention difficult. Furthermore, while Hong Kong generally does not impose controls on foreign exchange or restrictions on foreign investments, the company must nonetheless navigate the complex political landscape, especially concerning assets linked to erstwhile strategic interests like the Panama Canal ports. The wider portfolio of ports will doubtless raise further questions.

Given Li Ka-Shing’s extensive business empire, which includes significant holdings in both Hong Kong and mainland China, the sale of CK Hutchison's Panama Canal port interests could indeed invite indirect pressure on his other assets in the region. There is the possibility of heightened scrutiny from both the Chinese government and Hong Kong’s Administration. Li’s business decisions could be viewed as signaling alignment (or misalignment) with international interests, which might prompt regulatory or political pressures aimed at ensuring his future business activities are more in line with China's national interests, including its broader foreign and trade policy goals.

Due to Li’s close ties with Hong Kong’s financial sector, any potential fallout from the Panama deal could spill over into his investments in other sectors, such as banking, real estate, and infrastructure. There may be concerns among regulators and investors about the stability of his broader business interests if his dealings are seen as being too closely tied to Western interests, especially in the face of increasing de-dollarisation and rising geopolitical tensions. In essence, Li's assets in Hong Kong and mainland China could face indirect pressures if his Panama deal is viewed significantly negatively by Beijing or by Hong Kong’s authorities.

All that said and done, there is likely to be a recognition that any interventions would need to balance two principal considerations. Firstly, there is a need to preserve global confidence in the regulatory institutions in both mainland China and Hong Kong, and the relationship between the State and corporations. Hamfisted interventions would raise global scrutiny and increase the risk of global investor concerns about the ‘rule of law’ in both jurisdictions. Secondly, as I have suggested, the Panama Canal is of less significance today than it was; and further, that critical trends point to the increasing diminution of its strategic significance. Put plainly, the hard infrastructure alternatives being developed on the Latin American continent, coupled with the digital payments systems that are emerging not only there but also in the Caribbean, undermine what was once a strategic significance based on being a key choke-point to global trade flows. Those days are gone.

As for the remainder of Hutchison Port’s portfolio of ports, these will merit further detailed consideration.

A chip to deal?

Given the waning strategic relevance of the Panama Canal, China has limited economic incentive to prevent the sale of Hutchison Ports’ Panama assets to U.S. interests. However, political leverage and strategic signalling could still make it a useful bargaining chip in broader U.S.-China relations. The other ports can also form part of a wider set of considerations, though they do not have the same kind of ‘gate-keeper’ function that the Panama Canal facilities offer.

The sale of the Panama ports matters more to the U.S. than it does to China. The principal reason is political optics for domestic consumption. The Trump Administration would frame this as a “win” in countering China’s influence in the Western Hemisphere. This would be used as a talking point to show that the U.S. is “pushing back” against Chinese investments in strategic infrastructure.

As for China, its economic interests in the Canal will continue to diminish. With the rise of ULCV-focused routes and alternative trade corridors, Panama’s importance is declining for China’s long-term Latin America strategy. Selling these ports would not materially impact China’s ability to trade with the region, making it a dispensable asset.

As such, China could use it as a low-cost, high-impact tool for strategic manoeuvring. This would involve applying indirect pressure on Li to slow down the deal. Hong Kong regulators or mainland authorities could signal concerns over the transaction, delaying approvals or raising “compliance issues.” Since the sale is still in the due diligence phase, any additional regulatory scrutiny would frustrate U.S. buyers without materially harming Li Ka-Shing. Additionally, Chinese regulators or Li himself (in the face of pressure) could push for conditions that complicate BlackRock’s operations post-sale (e.g., access rights, licensing hurdles, labor agreements, or technology restrictions). This would increase costs for U.S. interests while keeping China’s options open for future influence.

Trump has flagged a desire to meet with President Xi Jinping in the near future. There are many issues on the bilateral agenda already. The sale of the ports could, in this context, be mobilised by China as a bargaining tool in wider bilateral negotiations. China could offer to “smooth” the sale of the Panama facilities in exchange for U.S. concessions in unrelated areas, such as trade restrictions, semiconductor policies, or financial access for Chinese banks. This tactic would maximise leverage without actually needing to keep the two ports.

From China’s point of view, it is conceivable that the goal is not necessarily to block the sale but to make it as frustrating and costly for the U.S. as possible—all while maintaining greater control over the timeline and terms of engagement. The deal, while relatively less important for China in economic terms, becomes a useful tool for strategic negotiation rather than a core infrastructure priority.

As for the remaining portfolio, that’s another matter altogether.

Note that of the portfolio, only the assets on the Panama Canal constitute monopoly or gate-keeper infrastructure. The other concessions relate to terminals at ports where there are other operators of other terminals.