This essay first appeared in Pearls and Irritations. P&I is an Australian-based international independent publishing platform, providing alternative opinions across a full range of issues. Please subscribe to P&I for independent perspectives, from an Australian point of view. A new social media alliance has also launched to amplify voices in favour of multipolarity, neutrality and ‘no to global NATO’. Check out www.multipolarpeace.com #MultipolarPeace #NoGlobalNATO

NATO has been shaping up to go global for quite some time. It has singularly failed as a so-called ‘defensive alliance’, having been involved in assorted bouts of warfare and bloodshed in Europe over the past three decades. Having come into existence ostensibly as a defensive bulwark against the threat of the Soviet Union, the dissolution of the USSR in 1991 should have spelled the end of NATO.

It didn’t.

Rather, NATO has - not unlike bureaucracies of times past - confected purposes for its perpetuation. Those purposes, much as was the case with its genesis, related to the presence of an external ‘enemy’ or ‘threat’. Without the Soviet Union, there would have been no NATO. Now, without the Soviet Union, there had to be someone else.

The ongoing eastward expansion of NATO - forsworn by the Americans in their negotiations with Gorbachev at the time - was pursued relentlessly in three rounds. Warnings about the risks to European peace and security were ignored; NATO and its American underwriter would insist that it was a ‘defensive’ alliance and no-one had anything to worry about.

Now, as NATO stares defeat in the face in Ukraine, it has set its sights on a global expansion. It has already had so-called ‘partners’ in Asia for some time. Japan, Republic of Korea, New Zealand and Australia all attended the NATO summit for the first time in 2022 where statements about the geopolitical challenges China poses were made. China was emerging as NATO’s new global bête noire. Russia was the immediate enfant terrible, but China was the real threat.

NATO tried to set up an office in Japan but was rebuffed by the French Government in 2023. Undeterred, however, NATO has chipped away and has in recent times worked to drag China into the Ukraine conflict, accusing China of supporting Russia through the provision of dual-use equipment. Jens Stoltenberg accused China of “inciting the largest military conflict in Europe since World War 2”. The US Ambassador to NATO Julianne Smith had claimed that ‘China has taken a side”. The Wall Street Journal (from the News Limited stable) on 7 July 2024 headlined an article with this: “China’s Support for Russia’s War in Ukraine Puts Beijing on NATO’s Threat List’.

All these accusations came in a flurry of a little over a week, in the lead-up to NATO’s Washington confab (9 July). Clearly orchestrated, with the view of rationalising NATO’s impending globalisation.

Where ‘A’ once stood for Atlantic, it would now include Asia.

While NATO’s expansion to Asia may be welcomed by the ‘insecurity apparatuses of state’ in Japan, ROK, Australia and New Zealand, it actually poses a substantial risk to the future of peace and security in the region. What NATO has done in Europe, it can do the same in Asia.

The reasons are straightforward and endemic to the rationale of NATO’s existence and modus operandi. In short, it is premised on the limited and often flawed ideas of ‘military deterrence’ as the principal means towards security, stability and peace.

‘Military deterrence’ is an approach that can deliver, at best, a negative peace. That is, so long as other assumptions hold (on which more shortly), military conflict can be avoided (deterred / prevented / deferred). But, deterrence doesn’t contribute meaningfully to the forging of the conditions and institutions necessary for a sustained positive peace.

You can’t achieve peace through security, but you can achieve security through peace, once remarked Johan Galtung, an early proponent of peace studies as an antidote to a militarised framework of ‘security’. Achieving a peace requires strategy, and an approach that is inclusive rather than exclusive.

By definition, NATO’s modus operandi is exclusionary; its existence is defined against a ‘hostile other’. To maintain a negative peace, a deterrence strategy can only work while one party is obviously more powerful than the others, and that the others are cowered into subordination. That’s what is sometimes described as achieving a balance of power where the ‘balance’ is, oxymoronically, in the favour of one amongst many. Asymmetry is not a condition for sustained stability, let alone peace.

Deterrence in fact is a strategy that has a high risk of failure. The best that anyone can get out of deterrence is that it buys you time. But, it cannot foresware others building themselves up (catalysing a security dilemma / arms race); indeed, arguably, efforts to impose an asymmetric power relationship is a surefire recipe for generating resentment. At some point, the risk is that such resentments boil over. The failure of deterrence doctrine in Gaza is a recent case in point, as Lawrence Freedman pointed out. Despite Israel’s obvious preponderance in hard power terms, Hamas nonetheless launched an attack on Israel forces in October last year.

Deterrence can become self-defeating, as it avoids the underlying issues that germinate conflict and focus, instead, on manipulating a narrowly defined military risk environment. So long as I am stronger than the others, the sources of conflict can be ignored. The risk is not only of attacks such as those mounted by Hamas, but a general increase in the probability of terrorist attacks. Little wonder that American political scientists Graham Allison and Michael Morrell have recently warned of the intensification of terrorism risks against the US and its resources.

Out-escalating an opponent may work for a while, but it is no panacea. In the end, the risk is that others join forces and can match up.

Yet, this is precisely the NATO doctrine. No wonder it has failed miserably to bring stability and peace to Europe during the years of American (western) unipolar superiority. On the face of it, despite being in its most secure position in living memory, the fact that the US initiated more military interventions between 1990 and 2019 than in any previous era is a paradox. But, understood through the lens of ‘deterrence doctrine’ it isn’t incomprehensible at all.

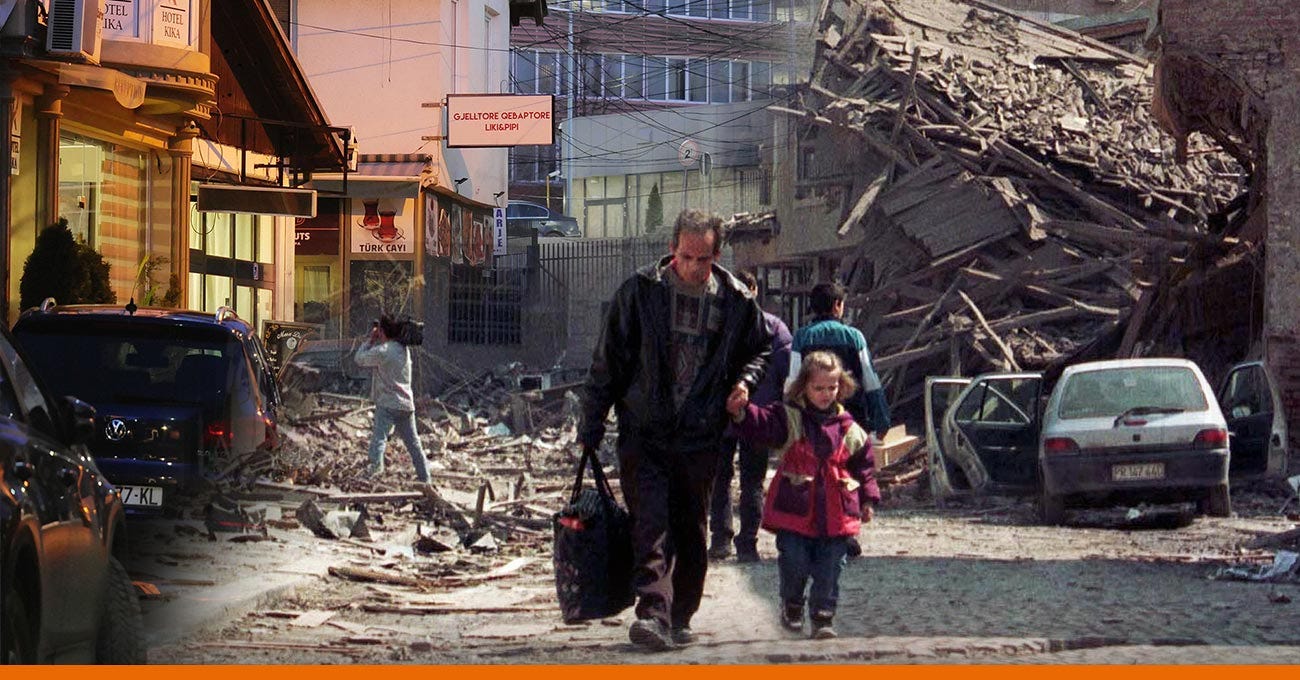

And so, NATO is angling to come to Asia. The black thumb of death and destruction has been the US-led collective west’s calling card. It’s about to leave it on our region's doorstep.

There are better ways. They are the ways of indivisible security, in which prosperity and peace are symbiotic. They are the ways of focusing on building a peace, rather than engaging in an arms war in the name of deterring war. They are the ways of a multipolar peace, in which security is found through peace and peace is built with collective prosperity.

A growing group of social media platforms has recently joined forces to amplify the voices of multipolar peace. We welcome the participation of others: www.multipolarpeace.com.