Transatlantic Concerns and Industry Realities: Chinese Manufacturing and New Electric Vehicles

Reflections on evidence and issues

This essay first appeared in Chinese on guancha.cn. What follows is an English version of the essay, though it’s likely that there are some minor differences. These differences are either a result of style of prose or a function of being able to add some additional materials in this English version, which has been published after the Chinese version ‘went to press’.

Motor vehicles have captured the human imagination for over a century. They have been objects d’art, marvels of engineering, symbols of national prowess and more mundanely, industries of employment and wealth creation. Motor vehicles are a means of transportation, a cause of congestion in our cities and towns and a source of carbon emissions.

From a manufacturing point of view, China has been a relative latecomer in a global sense, though its first domestically designed and manufactured passenger motor vehicle (PMV) came off the production lines in the 1930s. Car design and manufacturing has, for the best part of the 20th century, been the province of European design and engineering excellence, American industrial capacity, British doggedness and more recently, North Asian efficiency.

From the early 1950s through to the 1980s, Chinese car manufacturing volumes were modest, growing from 61 in 1955 to 222,288 by 1980. China’s motor vehicle industry has, however, been incrementally making its mark; first, in conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles with joint-ventures with foreign manufacturers, as well as a batch of local manufacturers emerging during the late 1990s through to the 2000s. By 2000, China was manufacturing over 2 million vehicles per year, and between 2000 and 2007 China’s auto market grew at an annual average of 21%. Indeed, since 2008, China has been the largest in the world in terms of the number of automotives produced; and since 2009, Chinese automotive output has exceeded 25% of global vehicle production. In 2009, Chinese automobile output hit 13.79 million vehicles, of which 8 million were passenger motor vehicles (PMVs) and the rest were commercial vehicles. By 2017, automobile output reached 28.88 million units.

Yet, it is in the field of New Energy Vehicles (NEVs) that has seen Chinese manufacturers take the ‘world by storm’. NEVs include both battery-electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids. The output and sales growth numbers over the past three years are staggering by any standard, albeit starting from an initial low base. As production volumes grew, so did export volumes. New NEV prices were also unprecedented. Chinese NEVs were on a like-for-like basis being delivered to market at retail prices 30-50% cheaper than competing alternatives from traditional PMV manufacturers.

Come 2023 and early 2024, European and American politicians have clamoured for protective measures in the face of what a number of western news outlets described as a plan to “invade Europe with electric vehicles”. European politicians have flagged moves to initiate an inquiry into allegations of Chinese NEV subsidies. Recently, American legislators have warned China against ‘dumping’ products onto the global market to, so it is claimed, “ease its industrial overcapacity problems”.

Against this backdrop, Chinese manufactured NEVs are increasingly framed as part of a broader set of tropes by the western mainstream media, think-tank commentators and many politicians, which claims:

China is suffering a manufacturing ‘overcapacity’ crisis, which leads it to ‘dump’ products onto the global market; and

That Chinese domestic consumption demand is insufficient, evidenced - so the argument goes - by deflation in the goods and services market.

This article explores these two related dynamics. In summary, a review of the data suggests two conclusions:

There is no ‘overcapacity’ crisis. As Chinese manufacturing output, including NEVs, has grown, so too has domestic demand for these products. China’s manufactured exports-to-production ratio shows that Chinese manufacturing today in general is less export-oriented than it was a decade ago; and

There is no contraction in domestic aggregate demand. Rather, Chinese consumption demand, including for NEVs, continues to grow and deflation is not a function of a contraction in aggregate demand but a result of increased supply due to productivity growth coupled with intense domestic competition in factor input markets.

In other words, the mainstream western claims are unfounded. Implications of this, insofar as western public policy challenges are concerned, are discussed at the conclusion.

Chinese Manufacturing in Context

China’s economic development over the past few decades has been premised on industrial expansion, as evidenced by the growing role of manufacturing. In 1995, China’s manufacturing value-added contributed about 5% of global total manufacturing value-added. By 2020 this had increased to 29%. In terms of global exports, China's manufacturing sector accounted for 3% of total global manufactured exports in 1995; by 2020, it accounted for 20%.

The standard narrative is that China’s economic development was based on exports, on the back of low labour-costs. Historically, there’s some truth in that but it has been superseded by the passage of time. A recent analysis of OECD trade in value-added data, by Richard Baldwin, shows that China’s manufactured exports-to-production ratio was 11% in 1995. It peaked at 18% in 2004 and has since receded to 13% in 2020. Production volumes have grown over the past three decades but it is clear from the exports-to-production ratio evidence that much of this output was absorbed by a growing Chinese domestic market. It’s worth noting that since COVID there has been a modest overall up-tick in the export-to-production ratio, with a large proportion of this absorbed by significant export growth to Russia.

Baldwin’s analysis also shows the evolution of Chinese manufacturing over the period from 1995 to now. In broad terms, the data shows that China has progressively moved up the value curve in terms of domestic production capacity. Until the mid-2000s, China was a net importer of intermediate goods and a net exporter of final goods (mainly in low-labour cost categories). However, from about 2002 onwards, China became a large net exporter of intermediate goods as well. China’s manufacturing profile has evolved from one relatively dependent on simple sectors like textiles and clothing to more complex sectors like electronics, fabricated metal products and chemicals and pharmaceuticals.

In 1995, textiles accounted for the largest share of Chinese exports; by 2020 that position was occupied by electronics. According to Harvard’s Economic Complexity Index, China has progressed from 39th in the world in 2000 to 18th in 2021, reflecting this shift from simple to increasingly complex manufactures. China’s emergence as a major manufacturer of not only PMVs but NEVs is reflective of this wider trend.

New Energy Vehicles

Global Markets

The global NEV car market has grown exponentially in recent years. Over 14 million NEVs were sold globally in 2023 accounting for about 18% of new car sales. This has grown from sales in 2022 of over 10 million, comprising 14% of all PMVs sold that year. This contrasts with 9% of all PMVs sold in 2021 and less than 5% in 2020. Sales in China accounted for about 60% of total global sales. Over 50% of all NEVs registered in the world are in China. The Chinese market is followed by the European market, in which NEV sales increased by 15% in 2022 with over 20% of PMV sales accounted for by NEVs. In the US, NEV sales in 2022 increased 55% reaching a new vehicles sales share of 8%.

Global demand for NEVs is expected to increase over the next decade or so. The main markets are expected to be China, Europe and the US though it should be noted that Thailand, Indonesia and India, and parts of Africa, are also expected to grow strongly but off lower bases. In Thailand, Indonesia and India NEV sales have more than tripled in 2022 compared to 2021, reaching a combined 80,000 units. In Thailand, NEV sales comprise 3% of new PMV sales and in the other two, EVs make up about 1.5% of PMV sales.

Market estimates, from industry analysts EV-Volumes, point to a global annual NEV market to grow from 14 million in 2023 to 73.9 million by 2035. In total, over the next 12 years (2024 to 2035), accumulated global sales is estimated to be 520.9 million vehicles (Figure 1). Of these:

Europe will account for 130.5 million (25.05%);

China 212.1 million (40.72%);

US 101 million (19.39%); and

Others 77.3 million (14.84%).

On an annual average basis, total global demand year-on-year growth is projected to be approximately 5 million additional units (with the range being 3.3 million to 6.6 million).

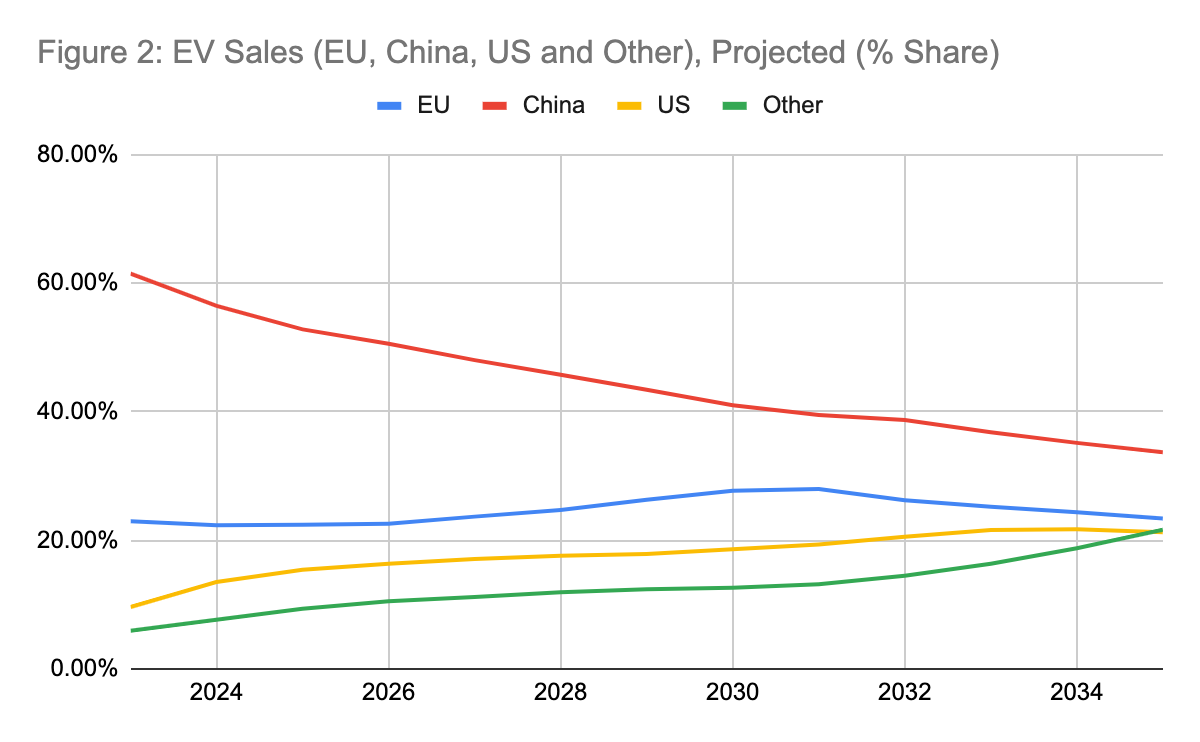

China’s overall share of the total global market is expected to fall each year from a high of 61% today to 33.7% by 2035 (Figure 2). Overall market share for the EU is expected to remain relatively stable, while market share from the US is expected to slightly more than double from 9.6% to 21.2%. The market share of the ‘other’ markets is expected to grow the most, from 5.9% in 2023 to 21.6% in 2035.

Before concluding this section on global demand dynamics, a number of conditions or caveats are necessary. Projections are subject to many variables. Government policies, overall economic conditions etc., as well as motor vehicle pricing. For example, significant real reductions in prices will likely lead to additional demand growth than the estimates presented above. Alternatively, subsidies or other financial incentives / disincentives could be introduced to support households transitioning from ICE vehicles to NEVs.

China’s NEV Sector

Production and Markets

China’s NEV production capacity has grown significantly in recent years. From a modest output of 17,533 vehicles in 2013, output rose to a little under 9.6 million in 2023. The expansion path has not been linear. Production output has shown a step-wise surge between 2020 and 2021 and again from 2021 to 2022 (Figure 3). The total China market for EVs in 2023 was around 8.3 million units, suggesting that domestic supply exceeded domestic demand.

In 2020, China exported about 350,000 NEVs. This rose to about 597,100 in 2021. According to the China Passenger Car Association, China exported 1.1 million NEVs in 2022, which comprised 15.6% of that year’s NEV output, and about 2.2 million NEVs in 2023 (23% of output). Some 840,000 of these exports in 2023 were directed to Russia. At the same time, China imported about 132,000 EVs in 2023. Over the course of the past four years, the domestic market has absorbed between 75% and 85% of output, in the face of rapidly growing production output. Conversely, exports have accounted for between 15% and 25% (Figure 4).

As production volumes have risen, so too have exports. This is shown in Figure 5. The data indicates that in the four years between 2020 and 2023, output increased by 8.225 million units or 602.5%. Of this output growth, the domestic market absorbed 6.37 million and the export market absorbed 1.85 million. Domestic volumes grew 628% between 2020 and 2023 with annual average growth of 1.59 million units, and export volumes increased by 528% with an annual average growth of 0.46 million. It is clear that the domestic market is significantly more important to the Chinese NEV manufacturing sector than is the export sector.

Looking forward, based on the forecasts discussed earlier, we can say that on an annual average basis, total China year-on-year demand growth is projected to be approximately 1.38 million additional units (with the range being 0.7 million to 1.9 million). This projected annual average growth is somewhat lower than the observed average annual change of 1.59 million between 2020 and 2023.

Demand Drivers

Demand growth in China for domestic NEVs has been underpinned by production scale and automation, fine tuned supply chains, combined with intense competition in both factor and end product markets, driving down costs and prices. Chinese NEV manufacturers are delivering vehicles to market at between 30-50% cheaper than counterparts from traditional manufacturers. According to reports, the “average EV in China cost around €32,000 (US$53,800) in 2022, compared to an average of €56,000 (US$94,100) in Europe.” Chinese NEVs are also comparably cheaper than ICEs with similar performance specifications.

Domestic competition is ‘cutthroat’, according to the New York Times, which reported on a price war in March 2023, which saw:

“Volkswagen’s Chinese joint venture slashed prices on its ID.3 electric cars by 18 percent. Changan Automobile, one of China’s state-owned car manufacturers, offered $3,000 cash rebates, free charging credits and other incentives for its electric vehicles. BYD, the country’s biggest E.V. maker, unveiled a second round of markdowns in a month for some of its older models.”.

The CPI for transportation and communications showed a downward trend in 2023 and early 2024. Overall, lower prices are creating a new market for NEVs amongst households for whom a new vehicle may have previously been unaffordable.

Intense price competition is sustainable only if productivity sustains cost reductions. In automotives manufacturing, the key has always been the ability to ‘take labour out’ (Williams et al, 1994). Automation is the driver of reducing the percentage of total costs associated with labour. Chinese manufacturers in general, and NEV makers in particular, are amongst the most active and aggressive when it comes to automation. According to the World Robotics Industrial Robotics 2023 report from the International Federation of Robotics:

Asia is the world’s largest industrial robot market with 404,578 units installed in 2022, an increase of 5% from the previous year;

73% of all newly deployed robots were installed in Asia;

Three of the top five markets for industrial robots are in Asia, with China being the largest market by far. In China, installations grew 5% in 2022 with 290,258 installations. In effect, 50% of robots installed worldwide in 2022 were in China.

Anecdotal data also indicates that new installed manufacturing capacity in the NEV sector is heavily capital intensive, with automated production lines now ubiquitous.

Analysis and Discussion

In recent months, there has been a chorus of western commentary about risks of Chinese NEV ‘over capacity’ leading to ‘dumping’ onto world markets. Based on the available data, this claim is at best tendentious. To meet project global demand by 2035, total global annual production capacity will need to increase by 60.4 million units from 2023 levels. Of this, by 2035, either by way of local production or imports:

The European market will need additional annual capacity of 14.2 million;

China will need 16.6 million;

The US, 14.4 million; and

Others 15.2 million.

This is shown in Figure 6. The ‘red’ sections in the Figure represents the gap that needs to be filled by 2035 compared to current levels of demand. Put plainly, over the next 12 years, there is significant projected demand that needs to be met through the installation of additional production capacity.

That China presently exports 15-25% of current output points strongly to a sector that finds most of its sales through servicing the rapidly growing domestic market. This is likely to continue for the foreseeable future, as Chinese domestic market demand is expected to grow overall by 212.1 million NEVs in total between 2024 and 2035. China’s current installed NEV manufacturing capacity would require augmentation to meet this need. Some of this augmentation may take place through the reorganisation of existing ICE vehicle production systems to meet the needs of the NEV market, while others will be met with additional greenfield capacity. Converting ICE facilities may be easier said than done, however. In other words, the unfolding market environment points to a need for China’s NEV sector to increase production capacity to meet growing domestic demand. This strongly suggests that claims of ‘over capacity’ are, prima facie, unfounded.

That said, China’s export growth is expected to continue solidly for the foreseeable future, all other things remaining equal. (The issue of trade barriers will be discussed below.) However, I expect the domestic market to be the main focus and cornerstone of the Chinese NEV sector. As far as exports are concerned, much of the growth has been to the ‘global south’ namely Brazil, Thailand, Central Asia, UAE and ASEAN countries, and in 2023 via exports to Russia. Exports to Europe account for about ⅓ of total NEV exports, according to reports in Bloomberg. Reports indicate that over the past 3 years, Chinese-made NEV market share in the European market has grown from 3% to 8% with expectations that it could grow to 15% by 2025 and higher by 2030. This remains conjectural, as many factors are at play, including whether legacy European manufacturers speed up their entry into the NEV market. So far, they’ve been quite slow.

To gain some insight into possible future dynamics, I have modelled a simple scenario based on existing market demand estimates referenced earlier, together with actual Chinese NEV production capacity growth between 2020 and 2023. In these years, production output increased on average each year by about 1.59 million units. Assuming that for the period 2024 to 2035 Chinese production capacity increases annually at this level (1.6 million), we find that:

Assuming 100% capacity utilisation, Chinese production output will exceed domestic demand by 1.59 million (2024) rising to 3.89 million (2035). However, in percentage terms, surplus production will fall from 14.2% (2024) to 13.5% (2035) with troughs of between 8-9% between 2026 and 2029. Note that BYD is achieving capacity utilisation of about 80% and Tesla 92%. This again suggests that there is no ‘surplus capacity crisis’, particularly when compared with the fact that the Korean automotive sector consistently exports over 60% of its output.

Surplus capacity accounts for 21.5% of forecast demand for Europe, USA and Others combined (2024), falling to 11.24% (2035). The remainder would in this scenario be met by other manufacturers, including those located in Europe.

In relation to total projected world demand (including the Chinese market), Chinese projected production capacity will account for 65.8% (2024) falling to 48.4% (2035).

See Figure 7.

In motor vehicles manufacturing, it is unlikely that all markets will be self-sufficient. This is because manufacturing cars is a complex and capital intensive business, which requires mature supply chains to sustain cost competitiveness. As such, not every country will have local car manufacturing. Trade is, as such, an inevitable feature of the motor industry. Given the above scenario, it is clear that China’s NEV sector’s market share globally will diminish over time, on straight line capacity expansion assumptions. Taking into account less than 100% capacity utilisation, China’s market share globally will be slightly smaller again as we look towards the future. It is conceivable that some of the estimated Chinese capacity will be developed offshore, reducing the proportion of Chinese-made NEVs without necessarily impacting the market share of Chinese NEV manufacturers.

The evidence does not support the panicked claims that Chinese NEVs are planning to “invade Europe”. In the overall schema of regional and global markets, while Chinese NEV manufacturers will continue to play significant roles, they will predominantly service the needs of a growing domestic market.

Claims that deflation portends a declining economy are misplaced. The experience of NEV market growth in China, in conditions of falling NEV prices, is a case in point. This finding is consistent with the results of a 2015 Bank of International Settlements research paper that investigated the relationship between output growth and deflation in 38 economies over 140 years. The paper finds that the relationship between deflation and falling output is “weak”. Instead, the paper observes that deflation is rarely a result of a contraction in aggregate demand but a result of increased supply brought about by productivity and intensive price competition. This would appear to be the case of China generally, and NEVs in particular.

Nonetheless, the rapid expansion of Chinese NEV production and aggressive pricing has clearly unnerved politicians in Europe and the US. The knee-jerk reaction is to consider the imposition of tariffs to counter the price advantage of Chinese exported NEVs; and in recent days, the Biden Administration has announced an investigation into the ‘national security’ risks posed by a future bevy of Chinese NEVs (‘connected vehicles’). The issue is much more acute for European policy makers than for Americans, in large part because Chinese made PMVs hold less than 3% market share in the US market and Chinese NEV PMVs also have little presence in North America. That said, the recent US experience with tariffs on Chinese goods is instructive.

In 2018 the Trump Administration launched a ‘trade war’ against Chinese products. Tariffs were imposed across numerous product categories, ostensibly to reduce the bilateral trade deficit and staunch jobs losses in so-called rust-belt regions. Recent research by David Autor and associates concludes that while the tariffs delivered a political dividend to Trump, in economic terms:

“The trade-war has not to date provided economic help to the US heartland: import tariffs on foreign goods neither raised nor lowered US employment in newly-protected sectors; retaliatory tariffs had clear negative employment impacts, primarily in agriculture; and these harms were only partly mitigated by compensatory US agricultural subsidies.”

There is little reason to believe that tariffs would in the case of European NEVs result in any net improvement in outcomes for European PMV manufacturers. Tariffs would, however, increase costs to consumers and pricing others out of the NEV market to the detriment of achieving carbon reduction targets.

European manufacturers are faced with the task of adapting production systems, and driving productivity growth through intensified automation and supply chain re-engineering. They also have opportunities to expand sales footprints into markets in which there are no local manufacturers. Same for American legacy manufacturers in Detroit. Even then, of course, they will face stiff competition. That said, Chinese partners may prove to be a better bet than ‘putting up the walls’. This is what Hungary is doing, and may point to a smart strategy for Europe as a whole. Interestingly, in Hungary’s footsteps, Italy’s government has already reached out to BYD to initiative discussions about BYD establishing a facility in Italy.