The Tortoise and the Hare in AI

Why the U.S. May Already Be Losing the Strategic Race

When it comes to artificial intelligence, the story of the last decade could be framed as a classic “Hare versus Tortoise” race. The U.S. sector, led by companies like OpenAI, Anthropic and Google DeepMind, surged forward with speed and ambition, chasing headline-grabbing breakthroughs in large language models, generative AI and advanced cloud infrastructure. The sector roared ahead with an intensity that seemed unstoppable: enormous capital inflows, aggressive hiring and relentless scaling of cutting-edge GPUs and data centres. But while the American AI ecosystem sprinted, a more deliberate, methodical alternative quietly built a foundation that may now be virtually unassailable: I speak of the AI ecosystem that has emerged in China.

At first glance, the U.S. appears to maintain the advantage. NVIDIA’s H100 GPUs, AMD’s MI300 accelerators and other American-made microprocessors remain the most energy-efficient digital compute engines available on the market. They dominate cloud AI, power cutting-edge research and form the backbone of commercial AI deployment. But these raw hardware advantages conceal other systemic vulnerabilities that China has been quietly addressing for years.

This essay explores these dynamics, and draws on some ‘back of envelope’ calculations and estimates to help understand the issues. These data parameters will need to be updated, corrected and refined as time goes on, as things are moving quickly, but the analytical structure below presents what I believe to be a useful and relevant holistic framework to assist in evaluating the extent of AI-competitiveness.

Energy Advantages

In the AI arms race, raw FLOPs1 are only part of the story. For large-scale models, energy costs, cooling overhead and total system throughput matter just as much; often more than peak chip efficiency. Here, the U.S. faces a structural disadvantage. Industrial-scale electricity prices in the United States are rising, currently averaging around $0.12 per kWh, while in China, large industrial regions serving AI clusters pay as little as $0.04 per kWh.2 Advanced node manufacturing relies on a fragile, geopolitically exposed supply chain and rare earth elements - essential for GPUs and other microprocessor components - are largely imported, leaving U.S. operations exposed to price shocks and disruptions.

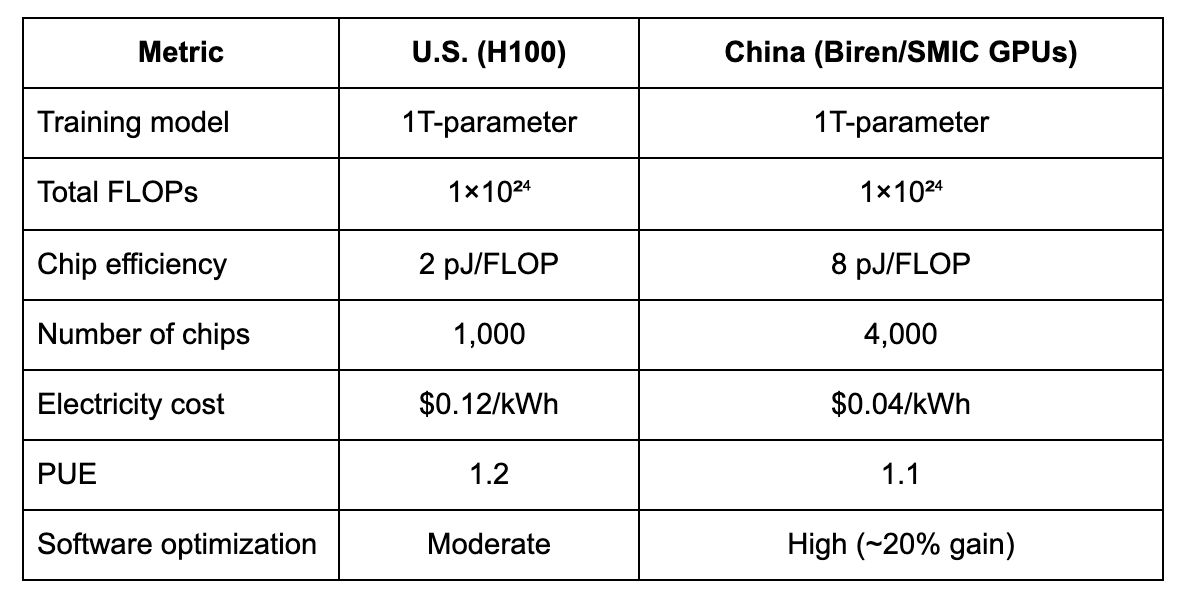

China, by contrast, has orchestrated a systematic advantage along every element of the stack. Its domestic chip production, including digital accelerators and a rapidly maturing suite of analogue AI chips, continues to improve steadily. Consider training a large 1-trillion-parameter AI model: a U.S. cluster using H100 GPUs incurs approximately $80,000 in electricity costs per training run, while a Chinese cluster, despite using slightly less efficient GPUs, achieves a cost of roughly $78,000 thanks to lower energy prices and software co-optimisation. Even on cost per joule of effective compute, the trajectory favours China; and the gap is likely to widen as U.S. electricity prices rise and Chinese energy remains stable or falls.

Even with lower raw chip efficiency, China achieves slightly lower total cost per training run due to cheaper electricity and software optimisation. Obviously, these estimates are sensitive to input parameters, so the claim here isn’t absolute precision but ‘orders of magnitude’ accuracy.

Table 1: US and Chinese Operating Performance Comparison

Calculations:

Raw energy per run:

U.S.: 1×1024 × 2×10-12 = 2×1012 J

China: 1×1024 × 8×10-12 = 8×1012 J

Total energy including PUE:

U.S.: 2×1012 × 1.2 = 2.4×1012 J ≈ 667kWh

China: 8×1012 × 1.1 = 8.8×1012 J ≈ 2.44MWh

Energy cost:

U.S.: 667k × 0.12 ≈ $80k

China (after 20% software efficiency gain): 2.44M × 0.8 × 0.04 ≈ $78k

China’s token-pricing advantage is already material. For example, Chinese models are being offered at a tiny fraction of the cost of comparable U.S. systems: ERNIE 4.5 from Baidu is priced at just ¥0.004 per 1,000 input tokens and ¥0.016 per 1,000 output tokens - roughly under 2 % of the cost of equivalent U.S. offerings. A broader survey shows Chinese-model output token costs of ~$2.19 per million tokens (for DeepSeek R1) contrasted with U.S. models charging tens of dollars (or more) per million tokens. See also this comparison of DeepSeek and OpenAI token costs. These pricing spreads are not small; they suggest China’s entire stack (hardware, software and energy) is already delivering compute at lower real cost. That means companies deploying AI in China or via Chinese infrastructure can train and infer models far more cheaply, thereby accelerating adoption. For the U.S., this signals that the competitive game is no longer just about capability, but about cost per token and how low one can drive it. Commodification is already upon us.

Analogue Advantages

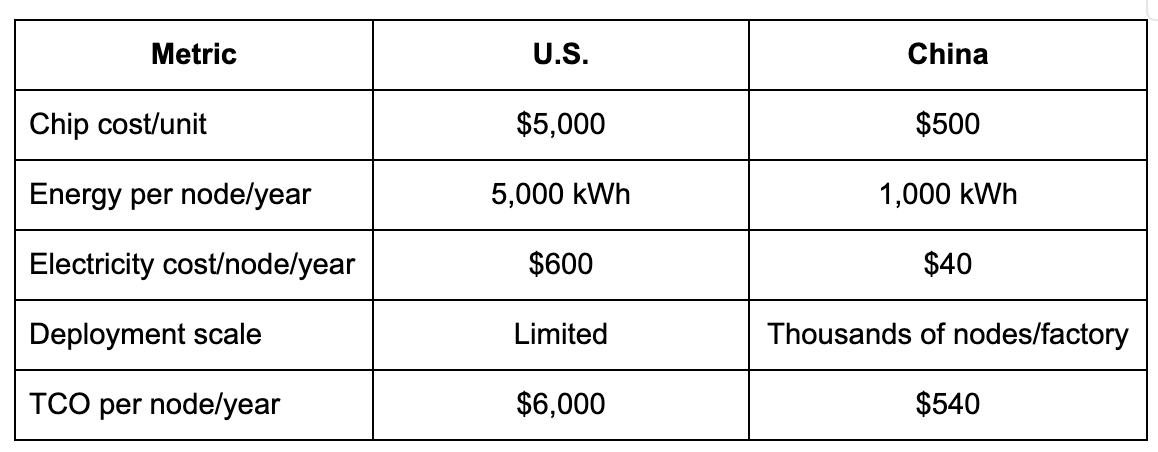

Much of the global attention has focused on digital GPU performance, but China’s growing dominance in analogue and neuromorphic chip design may be the true strategic lever. Analogue chips excel at industrial and edge AI workloads, including real-time control loops, computer vision and robotics. Their production cost is dramatically lower - typically around $500 per unit compared with $5,000 for a comparable U.S. digital chip - and their energy consumption per inference node is far lower (about 1,000 kWh per year versus 5,000 kWh).

Table 2: Analogue Chip Deployment – Industrial Automation, US and China Compared

Put plainly, China can deploy ~10× more nodes at ~1/10th TCO, enabling massive industrial acceleration and AI integration into factories, logistics, and smart infrastructure.

Analog chips differ fundamentally from their digital cousins. While digital processors execute logic operations at breathtaking speed, they remain useless unless they can interact with the real world. That interaction depends on analog devices: chips that convert light, sound, temperature and motion into digital signals, or condition and deliver the power required to run motors, charge batteries and operate communication systems.

These chips are pervasive. They are found in electric vehicles, where they manage battery systems, drive motors and enable safe, isolated communications between subsystems. They are embedded in industrial automation, where sensors, actuators and motor drives require precise analog circuitry. They underpin telecommunications and networking equipment, converting signals and ensuring reliable power supplies. And they are integral to consumer electronics and the Internet of Things (IoT), where even the simplest connected device requires a suite of analog components.

Unlike high-end processors, analog chips do not depend on the very latest lithography. They can be manufactured on “mature node” production lines - 28 nanometers, 40 nanometers, even 90 nanometers and above. What makes them valuable is not transistor density but design expertise, reliability and integration with end-use systems. For this reason, analog chips have historically been the domain of specialised firms with decades of accumulated know-how, such as Texas Instruments, Analog Devices, and ON Semiconductor.

The global analog chip market today is worth on the order of US$90–100 billion annually, accounting for 12 to 16% of total semiconductor revenues. While smaller in dollar terms than memory or logic, it is nonetheless a substantial share. Crucially, it is also poised for steady, long-term expansion.

Three structural drivers stand out.

First, the electrification of transport. Electric vehicles contain two to three times the analog and power semiconductor content of traditional internal combustion engine vehicles. As EV adoption accelerates, demand for battery management chips, gate drivers, power conversion ICs and automotive networking transceivers will grow commensurately.

Second, industrial digitalisation. Factories, logistics hubs and urban infrastructure are increasingly being equipped with sensors, connected devices and automated control systems. Each deployment expands the installed base of analog components. Importantly, once industrial customers validate a supplier’s chip for safety and reliability, they are reluctant to switch. The result is long product lifecycles and recurring revenues.

Third, the Internet of Things. Despite years of hype, IoT remains in its infancy. Tens of billions of devices are envisioned, but only a fraction have been deployed. Each IoT node requires analog front-ends, converters, amplifiers and power regulators. As IoT matures, the analog content will multiply, providing a durable growth engine for decades.

Put simply, the analog sector represents the substrate layer of the digital economy. High-end processors may make headlines, but without the analog infrastructure, they cannot function in the messy, physical world. From Beijing’s perspective, the analog market is attractive precisely because it is both critical and accessible. Competing head-on with U.S. and Taiwanese firms at the leading edge of digital logic remains a formidable challenge, constrained by export controls, extreme ultraviolet lithography and entrenched incumbents. China’s ecosystem remains in catch-up mode, though it is fair to say that for now, China has weathered the storm.

But analog semiconductors are a different story.

Analog production does not require the world’s most advanced fabs. It can be undertaken at mature nodes, where China already has significant manufacturing capacity in firms such as Hua Hong and SMIC. At the design level, Chinese firms such as SG Micro, GigaDevice and Will Semiconductor are scaling up capabilities in power management, automotive interfaces and sensor integration. The technological barriers are real - analog design is as much art as science - but they are lower than those facing entry into the 2-nanometer race.

This creates important advantages. Domestically, China can accelerate AI-driven industrial automation at scale. Thousands of nodes per factory can be deployed at a fraction of the total cost, enabling wide-scale smart manufacturing and logistics networks. In contrast, the U.S., constrained by higher chip and energy costs, can deploy only limited nodes, constraining industrial AI adoption. For example, over five years, a typical U.S. industrial AI cluster might scale to 1,600 nodes, while China could deploy nearly 38,000 nodes across factories, compounding both technological impact and economic leverage.

Hardware-Software Co-optimisation

Hardware alone does not win AI races. Software frameworks, model optimisation and co-design between chips and compute workloads are equally critical. Chinese firms have invested heavily in hardware-software co-optimisation, enabling analogue and less-efficient digital chips to achieve throughput comparable to high-end U.S. GPUs. China is making significant strides in hardware-software co-optimisation to enhance its AI capabilities. This synergy is especially pronounced in industrial automation, where energy efficiency, latency and integration with real-world sensors are critical.

A notable example is Huawei’s development of the Ascend AI chip series, which is complemented by the CANN (Compute Architecture for Neural Networks) software stack. Huawei has recently announced plans to make CANN open-source, aiming to challenge NVIDIA’s dominance in the AI accelerator market. Another example is DeepSeek’s release of its large language model, DeepSeek-V3.2-Exp, which is optimised for Chinese-native chips and software. This model supports domestic accelerators like Huawei’s Ascend NPUs and Cambricon’s MLUs, demonstrating China’s push for AI sovereignty by prioritising domestic hardware in frontier AI development

These initiatives reflect China’s strategic focus on integrating hardware and software development to reduce reliance on foreign technologies and strengthen its position in the global AI landscape.

In effect, a Chinese deployment could arguably deliver 2–3 times the energy-adjusted compute per dollar compared with U.S. alternatives. This is a structural advantage that compounds over time, particularly as scale increases. Even if this advantage was smaller due to tighter energy cost differentials, it is clear that the U.S. does not command any obvious superiority.

Rare Earth Elements

Beyond energy and chips, China’s dominance in rare earth elements and critical fabrication inputs underpins its broader advantage. While the U.S. remains reliant on imported materials for GPUs and high-capacity batteries, China maintains a secure domestic supply. This not only reduces cost volatility but ensures that large-scale deployments of AI and industrial automation are insulated from global shocks. As global demand for AI accelerators, batteries, and robotics grows, the U.S. may face supply bottlenecks that Chinese firms can largely avoid.

In October 2025, China announced expanded export controls on rare earth elements, adding five new materials to its restricted list and requiring export licenses for any goods containing Chinese-origin rare earths. These controls target critical materials essential for semiconductor manufacturing, including dysprosium, terbium and yttrium. Given China’s dominance in rare earth processing - accounting for approximately 90% of global capacity - these measures could disrupt the supply chains of U.S. microprocessor manufacturers if they are for non-compliant purposes. Military uses are in principle not permitted, and dual-use purposes will require application and resolution on a case by case basis. Companies that depend on these materials may face delays in production and increased costs, potentially affecting the timely delivery of advanced chips used in AI, defence and consumer electronics sectors.

While negotiations between the US and China have stayed the application of these licensing requirements for 12 months (31 October 2025), it is clear that this regime presents China with an ability to manage the supply of key materials, particularly those that impact national and global security.

The AI-in-a-Container Model and Open Source

Perhaps the most striking development is the emergence of containerised AI systems leveraging open-source models. Chinese firms are packaging AI stacks - compute, software, energy and communications - into turnkey solutions deployable in regions with minimal local infrastructure. These solutions can reach developing economies directly, reducing reliance on U.S.-based cloud services and proprietary models.

China is making significant strides in deploying AI solutions through containerised, plug-and-play systems, aiming to provide accessible and scalable AI infrastructure. For instance, Alibaba Cloud’s deployment of the Qwen-VL-Chat model demonstrates how AI applications can be rapidly set up using containerised environments, facilitating efficient deployment and management. Additionally, Huawei’s contributions to the Cloud Native Computing Foundation, including the donation of Volcano for high-performance AI workload scheduling and KubeEdge for edge AI container deployment, highlight efforts to streamline AI infrastructure and enhance deployment flexibility. These initiatives reflect China’s strategic focus on integrating hardware and software development to reduce reliance on foreign technologies and strengthen its position in the global AI landscape.

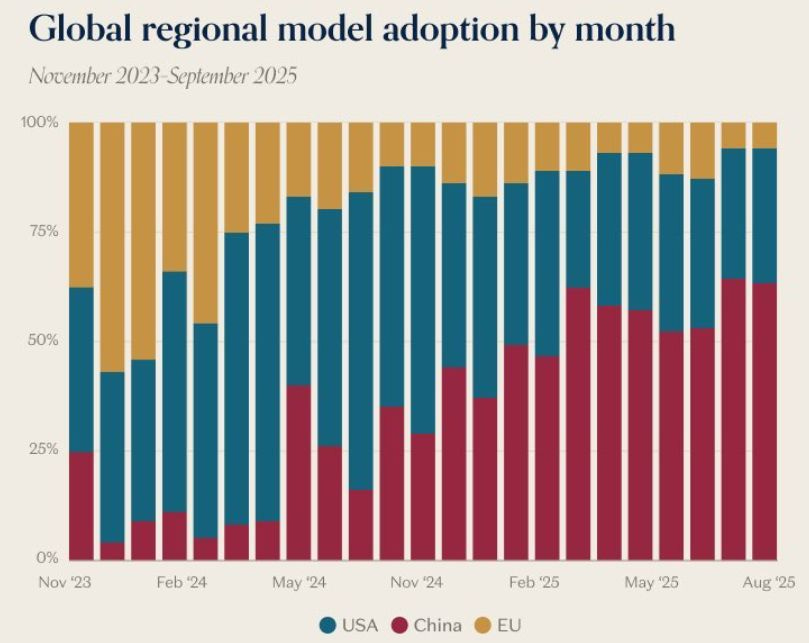

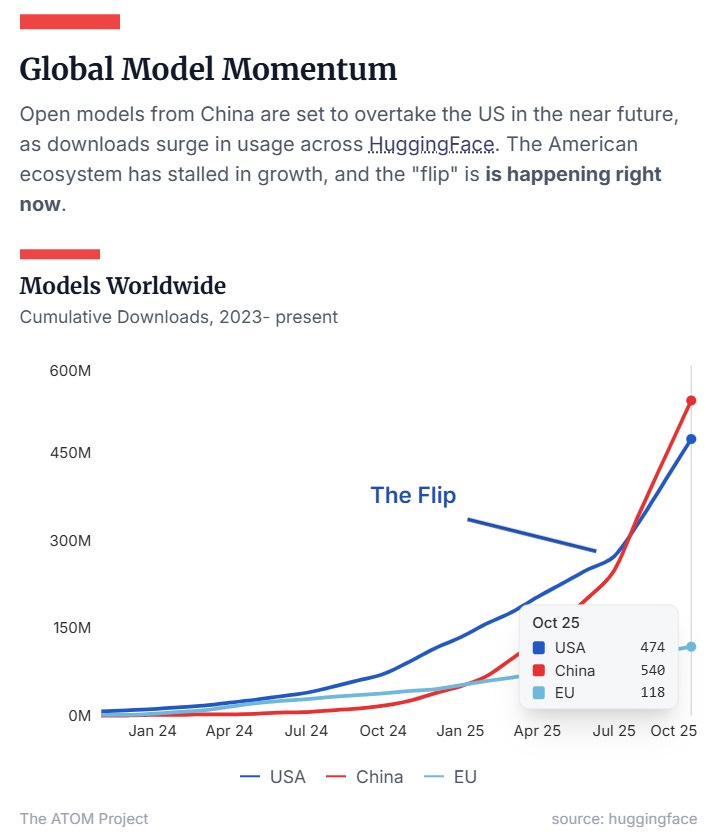

On the open-source/download front, China is also gaining traction at speed. Chinese model families such as Qwen 2.5 (from Alibaba Group) have reportedly been downloaded tens of millions of times. Meanwhile, various commentaries suggest Chinese open-source models are now out-pacing U.S. equivalents in global adoption, with one slide citing >60% share of open-model deployments emanating from China (Chart 1). That combination of low cost and broad adoption means the ecosystem effect (developers, deployments and services) is tilting toward China. U.S. firms, reliant on proprietary models and higher cost‐structures, may struggle to maintain base‐model moats if global developers increasingly rely on lower-cost Chinese alternatives.

Chart 1: Global Regional Model Adoption by Month

Cumulatively, these trajectories have seen Chinese open-source models overtake those from the U.S. (Figure 2). Even American enterprises are adopting the Chinese open source models as the foundations of their own development work, as reported in a recent issue of Harvard Business Review. Sceptics argue that the commodification of AI compute and the drive to lower costs will undermine long-run sustainability. We’ve seen these arguments run before when it comes to other cutting edge sectors, ultimately to see industry consolidation with prices established at close to marginal cost, but with those that achieved marketshare growth during the heady days of intense competition surviving to prosper.

Chinese AI providers are now offering migration services to support their clients to seamlessly switch from Claude AI models to indigenous AI tools that match performance but cost less. Anthropic has pushed back by banning Chinese-owned entities from running Anthropic AI services (as if this is going to matter), while doubtless American AI tech will raise the ‘geopolitical’ temperature seeking regulatory protections in the name of security. The downside risk is that such moves could boomerang, and lead to the isolation of American AI tech.

Figure 2: Global Model Momentum

The implications are significant. Proprietary U.S. AI models, once a central source of revenue and influence, are increasingly undercut by plug-and-play open-source stacks that integrate fully with local energy and communications infrastructure. The result is that U.S. firms may increasingly compete with European and open-source providers for influence in traditional markets, rather than enjoying dominance through proprietary technology.

Cash Flow and Reinvestment Dynamics

The financial implications reinforce the structural challenge. Chinese firms, capturing higher margins from lower-cost energy and hardware, can reinvest aggressively in next-generation chips, software optimisation and industrial AI deployment. In contrast, U.S. firms, facing rising operational costs, supply chain fragility and erosion of base-model moats, may experience declining margins, constraining reinvestment and innovation.

As Chinese AI firms leverage lower energy costs, domestic chip production, and software-hardware co-optimisation to deliver AI at reduced total cost, U.S. companies face increasingly compressed margins. High electricity costs, expensive imported components and limited deployment scale reduce profitability per model or per deployment, constraining the cash available for reinvestment in next-generation research. This financial pressure is compounded by the erosion of proprietary base-model moats, as open-source, containerised AI stacks from China and perhaps even Europe capture markets that were once expected to be lucrative well into the future.

Reduced margins limit the ability of U.S. firms to fund long-term R&D initiatives, experiment with novel architectures, or scale new industrial AI applications. Over time, this creates a self-reinforcing disadvantage: lower profits reduce reinvestment, which slows innovation, further eroding competitive positioning relative to Chinese firms that enjoy both lower operational costs and higher cashflow for continuous development.

Implications for the U.S. AI Industry

The cumulative effect of these factors is stark. Rising energy and operational costs limit competitive scaling in U.S. data centres and industrial deployments. Hardware scaling constraints and higher per-unit cost reduce the competitiveness of U.S. digital GPUs versus Chinese analogue and co-optimised chips. Supply chain exposure heightens vulnerability to geopolitical shocks and price volatility. Industrial automation leadership shifts toward China, with wide deployment of analogue AI chips accelerating industrial digital transformation. Base model erosion through open-source, plug-and-play AI stacks diminishes revenue streams and U.S. influence in emerging markets. Reinvestment gap constrains innovation in next-generation AI hardware and software.

If current trends persist, the U.S. may find itself competing primarily with Europe and open-source ecosystems for influence in global AI adoption, rather than with China directly. Its early sprint advantage, while headline-grabbing, may translate into diminishing long-term strategic leverage.

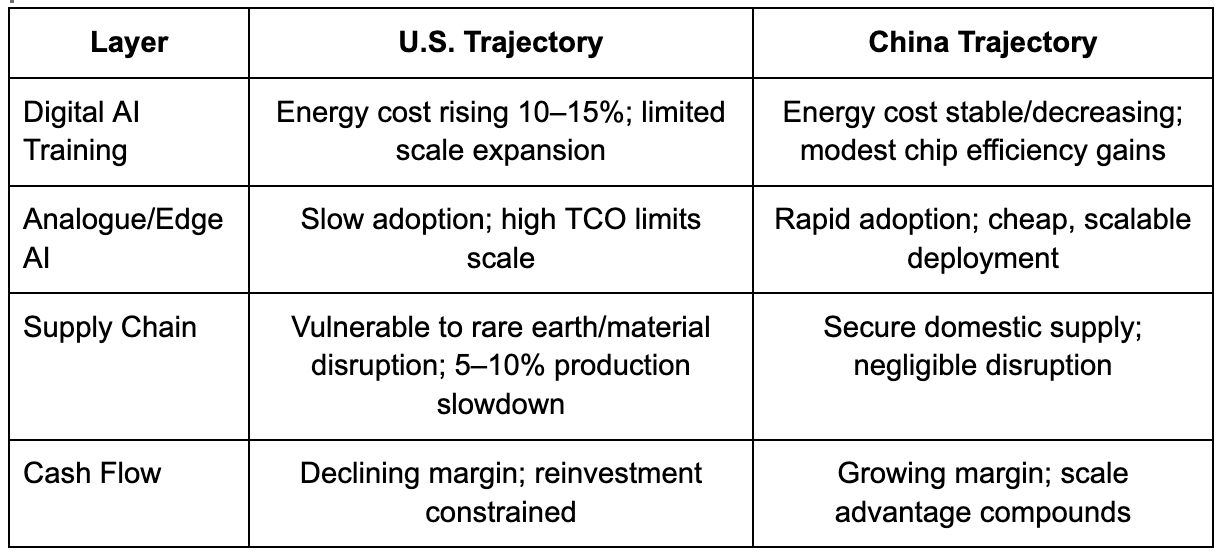

Table 3 summarises a comparative evaluation of the trajectories across various ecosystem layers for the US and China’s AI ecosystems.

Table 3: Layered Scenario: US and China

In quantitative terms, it is not unreasonable to say that the results could be that aggregate energy-adjusted output per dollar invested will see China likely 2–3× U.S. by Year 5. As for industrial AI node deployment, China outpaces the U.S. by ~5–10× nodes. And, in terms of cumulative cash flow China’s reinvestment in hardware/software exceeds the U.S. by >50%, further widening the gap.

The Tortoise Surpassing the Hare?

The story of AI’s global race is shifting from speed to sustainability, integration and systemic efficiency. While the U.S. sector sprinted ahead, China has quietly built a layered, resilient and cost-effective AI ecosystem. Its advantage is embedded in energy arbitrage, supply chain security, analogue chip dominance and open-source integration that reaches the developing world.

In the classic fable, the Hare was fast but overconfident, while the Tortoise moved deliberately and steadily, ultimately winning the race. In the AI landscape today, China embodies the Tortoise. Its position is not built on headlines or speed alone, but on careful engineering, cost optimisation and strategic foresight. The U.S., despite its early sprint, now faces a race in which catching up may require structural interventions of unprecedented scale in energy, industrial AI deployment, and microprocessor manufacturing. These are challenges that are as political as they are technical.

The competitive landscape is likely to be characterised by a number of key parameters. The ongoing expansion of the role of open-source models. Chinese firms will continue to release models integrated into plug-and-play stacks, reducing dependency on U.S. proprietary base models. At the same time, turkey AI solutions will likely become increasingly prevalent, especially for the developing economies. As recent developments show, AI stacks can be containerised with embedded energy systems and communications arrays, deployed without large-scale data centre infrastructure. For the US, this means that proprietary model revenues face erosion risks, while hardware and software margins compress. These dynamics compound to reduce overall leverage over industrial AI deployment, accelerating US loss of market dominance potential in both cloud AI and industrial automation.

I close-out with a cautionary note. The related technical and scientific fields impacting these dynamics are in flux; developments and advances continue to take place, making the parameters ‘unstable’. But, if there’s a core tale to take from this assessment, it is that claims about AI leadership based on one dimension of an overall system are misleading, and it pays to look at things through a complete ‘supply chain’ lens. And in supply and industrial chains, China is doubtless a global leader.

FLOPS (floating-point operations per second) is a metric for a processor’s computing power. It measures how many complex calculations involving decimal numbers it can perform per second. It is used to measure the speed and efficiency of AI systems, with higher FLOPS indicating greater processing capability.

Doubtless, there is some fuzziness on the question of the typical industrial price for electricity charged in each country. Different to the prices I use in the calculations in the body of the essay, other research argues that n 2025, Chinese industrial electricity prices were approximately $0.077 per kWh, while while U.S. industrial electricity prices averaged around $0.148 / kWh. So, the discussion is based on a broad notion of ‘orders of magnitude’ difference.