The China Simulacra Machine … and then, there’s reality

Let's try the 'red pill' and see what there is

China’s ‘Two Sessions’ has been going. on for the past week. A big topic, unsurprisingly, is the economic situation and what’s in store for 2024 and onwards. In parallel, the western mainstream media has been working up a host of myths and tropes for the past six months, at least. This short essay dissects these.

All societies need their own myths, about themselves and about others, to function. Anyone who’s familiar with Roland Barthe’s famous collection of essays, Mythologies, will appreciate this. But problems arise when mythologies stray too far from what Jean Baudrillard called the “sacramental order” - that is, a foundational reality that continues to evolve, regardless of what our myth-makers may tell us.

In the first Matrix movie, Neo stores his USB sticks in a box disguised as a book. It’s no surprise that the ‘book’ is Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation. What we have, in relation to China generally and in recent times China’s economy, is a Simulacra Machine on steroids. China is, according to various western mainstream tropes, on the edge of the precipice of collapse (or in fact, it’s been collapsing on and off for the past two decades) or alternatively, preparing itself for world domination. These are mythologies that more resemble simulacra; the make-believe world of those who prefer the comforts of mythologies to the complex and nuanced greys of reality.

If you prefer the comfort of the simulacra, the blue pill is for you. If, however, you prefer to see the world as it is, then it’s time to try the red pill. Let’s go ….

The China collapse thesis revolves around a series of tropes. These tropes come and go, but are often intertwined. I will examine each in turn.

Trope 1: China’s economy is weak and slowing

This is usually contrasted to descriptions of the US economy as “performing better than expected etc. Those with a penchant for media and discourse analysis could spend many fruitful hours exploring the rhetorical differences.

China’s economic growth, measured in terms of GDP change, is slower today than it was five years ago; it’s slower than it was ten years ago. According to the IMF, in 2023, China’s GDP grew 5.2%. This is the second highest of any economy in the world. India ranked first, though India’s starting baseline is about 6 times smaller than China. The US economy grew 2.5%. China’s GDP growth is forecast to grow 4.6% in 2024. Again, this puts it second behind India. The US is forecast to grow 2.1%, the Eurozone 0.9%. China’s growth rate is on track to meet its self-stated 2035 objectives.

Trope 2: China has excessive productive capacity, suppressed or weak domestic consumption, resulting in deflation

This forces China to unfairly dump cheap manufactures onto the world market. There are a few parts to this thread of ‘reasoning’, so let’s deal with each in turn.

China’s share of global manufacturing value added has grown from 5% in 1995 to 29% in 2021. Over that period, the share of exports to manufactured goods output has risen from 11% to 18% (2004) and is now tapering back to historic levels, reaching 13% in 2021. In other words, as China’s manufacturing output has grown the overwhelming majority has been absorbed by a growing domestic market. See the research note from Richard Baldwin for further details.

This immediately suggests that claims about suppressed demand are questionable, to say the very least. Chinese household consumption grew 9.2% in 2023. Household incomes have more than doubled in real terms since 2012. Household incomes in 2023 increased 6.2% over the previous year (Reference: National Bureau of Statistics of China). As a percentage of GDP, household incomes have increased from 55% in 2008 to 69% in 2023. Lastly, the GINI coefficient, the most common statistical measure of income inequality, has fallen substantially from 43.7 in 2010 (the peak) to 37.1 (2020), according to the World Bank. The reason why income inequality measures matter is because this is often raised as an explanation for why China’s household consumption levels are supposedly weak.

Deflation in China is evidence of a lack of consumer confidence, ergo an economy in crisis. There’s bad deflation and good deflation, as researchers at the Bank of International Settlements have noted. Bad deflation is when prices fall because of a contraction in aggregate demand. This is NOT what is happening in China. The BIS researchers actually note that, “deflation may also result from increased supply. Examples include improvements in productivity, greater competition in the goods market, or cheaper and more abundant inputs, such as labour or intermediate goods like oil. Supply-driven deflations depress prices while raising incomes and output.” It is clear that national output is rising, as is aggregate consumption and incomes.

Deflation: a specific case - pigs and pork. Recently, Bloomberg ran a story arguing that falling pork prices pointed to an economy in crisis. However, while prices have fallen, this has not been because of a fall in demand for pork.

In fact, data shows that pork demand has been growing strongly post-COVID and in response, so has pork supply. Pork supply volumes in 2023 have risen to highs not seen since 2013. What’s happened is that as pork demand grew, pig producers committed heavily to breeding additional supply and have ‘overshot’ the mark. (Ironically, it’s worth noting that back in late 2022, Asia Nikkei spoke of a 'porkflation crisis’ … you can’t win either way, by the looks of it.)

Trope 3: the residential property sector downturn speaks of impending crisis

The residential property sector has experienced a downturn. This was engineered through a concerted raft of policies aimed at curtaining credit growth in response to rising concerns of excessive leverage. In late 2017 the then Governor of the People’s Bank of China spoke explicitly about concerns of a ‘Minsky Moment’. At the same time, President Xi Jinping sent a signal to the industry: ‘houses are for living in, not for speculation’. Efforts to rein in property-secured credit were on the cards. Credit growth rates to the property sector were eventually curtailed. Real estate development loans grew 1.5% YoY at the end of 2023, compared to 3.7% for the previous year. It was over 20% in 2018.

Most development companies in the industry heeded the message or responded to the contraction of credit through active deleveraging. Some didn’t. Those that didn’t sought to raise credit offshore, through for instance the issuance of corporate bonds on the international market. This is what Evergrande, for example, did. But in the scheme of things, the overall property sector is experiencing a managed deleveraging. Of course, there are bumps along the way, as any process of balance sheet repair inevitably has. Funds are being provided to enable projects to be completed, so that people who’ve purchased off-the-plan get their apartments. But don’t expect international bondholders (or the executives of the development companies) to be helped very much.

None of this points to a national economic crisis.

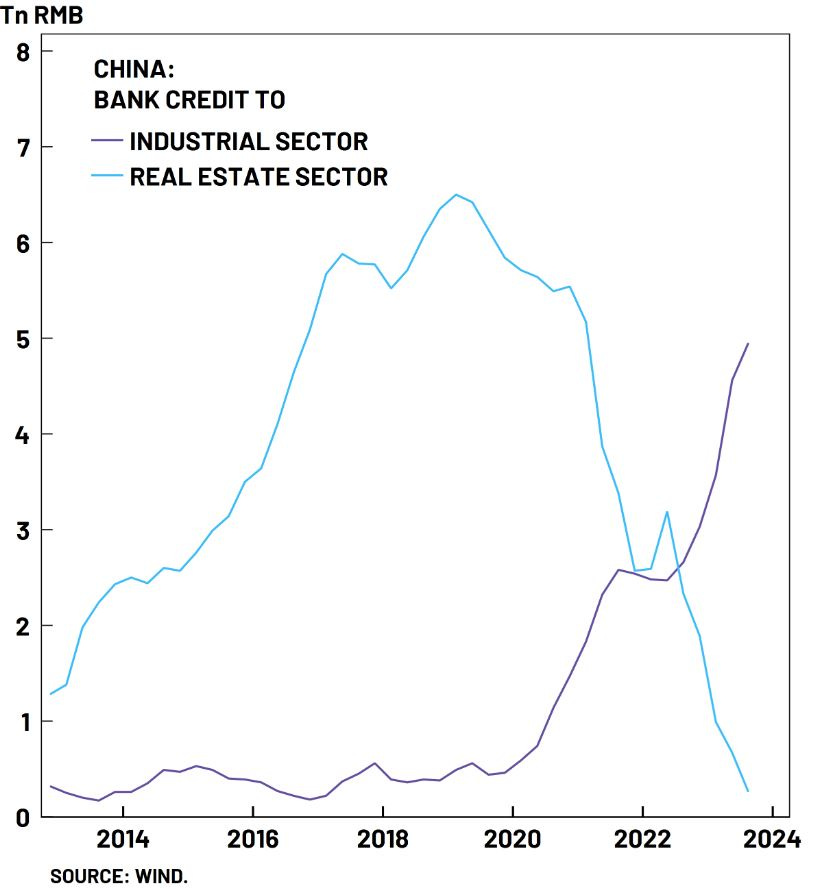

In fact, the contraction in the residential real estate market is part of a broader restructuring that’s taking place. Not only has the contraction of credit to the sector been focused on reducing leverage risk, it’s also been part of a policy initiative to overcome what has in effect been a ‘Dutch Disease’ problem. Dutch Disease is when rapid growth in one sector draws resources to it (and by definition away from other sectors), leading to imbalances in the economic development potential of the economy overall.

A few years ago, the residential property market contributed about 30% of GDP. That’s now down to about 18%. Credit contraction in the residential property sector was accompanied by credit expansion in the industrial sector. Indeed, private investment in non-property sectors grew during 2023 by about 9%. In other words, there’s a structural transformation happening that is seeing high-tech, science and technology and manufacturing emerging as the new driver of economic growth in lieu of the residential property sector.

Trope 4: collapse in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

There’s been a bit of a brouhaha around China’s 2023 FDI data. A commentary from BNP-Paribas from late last year is a useful “keep the feet on the ground” kind of piece. It observes:

Companies in China have been repatriating profits since 2016;

US interest rate hikes have made China FDI relatively less attractive. Note that FDI usually involves commitment to fixed capital, with long times involved to realise returns, whereas Treasuries can be relatively short; and

The note also touches on evolving sentiment, which I find the least “concrete” of the observations. Importantly the note points out that FDI comprises 3% of investment activity in China, it’s thus not “that” significant; and

Last, the BNP note also observes a global shift in FDI to China pointing to a shift towards the Gulf States. This is reflective of longer term trends.

In addition to these observations, I would suggest there’s also some structural features at work. The repatriation of profits from companies long established in China is because many of these are involved in industries that aren’t that attractive for continued investment. These are part of the early waves of foreign firms involved in labour intensive, low capital-to-worker ratio, activities. These activities are now “cash cows” being milked but any further capacity augmentation is likely to take place offshore, where overall production costs are lower. The second dynamic is the growth in Chinese firms in the leading edges of complex manufacturing. In some ways this investment expansion is “crowding out” foreign firms.

All in all, none of the data points to an economy in crisis, let alone one on the verge of collapse. That’s good news for Australia, actually. Incidentally, if China’s economy has been effectively gasping for air for the past 12 months, one wonders how we would go about explaining the fact that its trade with Australia during that period exceeded $200 billion to reach record highs.

China’s economy is in transition. There’s no doubt about that. This transition involves a significant shift from urbanisation and property development as drivers of growth, to industrial development as the underpinnings of productivity-driven expansion. Household incomes are rising strongly, as is household consumption. Domestic demand is expanding, as is supply capacity. And when you mix all of that with intense competition, you get downward pressure on prices; that’s ‘good deflation’. Private investment (and public / SOE investment) is also growing.

Talk of China’s economy on the verge of collapse is a figment of an overactive imagination; it’s the Simulacra Machine on steroids. Modest mythologies is one thing, but to peddle myths that are so detached from the sacramental order is a disservice to all concerned.