As President-elect Donald Trump announces nominees for his Cabinet, there’s plenty of discussion as to what the personnel may mean in terms of the next Administration’s policy towards China. Some speculate as to what a ‘transactional’ Trump may be willing to do, seeing this as something of a window towards a pragmatic ‘deal oriented’ relationship. Others muse that Trump has an aversion to warfare, preferring to pitch him as a ‘peace president’. On this score, the prognostication is that talk of conflict between the United States and China in the near-term will recede, even if there remains intense animosity towards China from amongst the Congressional political class and the Washington foreign policy establishment.

Speculative analytics is part and parcel of the world of political punditry. Utterances of individuals will be parsed, in the hopes of divining some insights into present attitudes and future actions. Rather than hang on the words of individuals per se, hoping to gain some grip on how a particular individual may or may not behave, we can gain some insight into what attitudinal and policy parameters are likely, by revisiting the institutional-cum-cultural milieu that is the American foreign policy establishment. I call it the Beltway Milieu.

The presupposition behind this claim is that individuals are, to large extents, creatures of their milieu, and that far from being a disruptive outsider, Trump as president - and his executive team - will be largely constrained and framed by the parameters of the institutional-cultural milieu. Another way of thinking about this is to view this as an ‘agency envelope’ - that is, the room in which individual actors can or are likely to, frame the world around them, and therefore, the kinds of possibilities that they can contemplate as responses.

No mood for peaceful co-existence

Paul Heer, an American foreign policy and diplomatic historian, reported in his recent essay published in The National Interest on the feedback he gleaned at a private conference that discussed how the US and its allies should pursue a strategy in the so-called Indo-Pacific to “deal with the challenge from China”. Heer concludes that the American foreign policy establishment has no interest in peaceful co-existence with China.

He observes that, “the prevailing sense was that engagement with China had become highly problematic, if not futile, largely because Beijing’s strategic ambitions leave little room for either accommodation or peaceful coexistence”. Within this frame, China was unsurprisingly being blamed. He goes on to argue that, “even China’s minimalist goals were deemed by many conference participants to be both immutable and irreconcilable with US and allied interests".

This basic posture should come as little surprise to most observers who’ve paid any attention to American policies towards China in the last decade or so. Indeed, it was clear that the policy establishment had, by at the latest around 2017/18, come to the view that “engagement” had failed.

In a special issue of Foreign Policy in March 2018, evaluating the effectiveness of multiple decades of “engagement”, Kurt Campbell and Ely Ratner concluded that, “Neither U.S. military power nor regional balancing has stopped Beijing from seeking to displace core components of the U.S.-led system. And the liberal international order has failed to lure or bind China as powerfully as expected. China has instead pursued its own course, belying a range of American expectations in the process.” For them, China had “defied American expectations”.

This view was confirmed by Biden Administration National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan in an address in February 2024, in which he lamented the failure of decades of American effort to “shape or change China”. Engagement was one set of tactical approaches to a wider set of strategic ambitions: to “shape or change” China. Engagement should not be understood in any other way; certainly not as some pathway towards the peaceful coexistence of equals.

Realpolitik and America’s Posture towards Asia

America’s ambitions to shape China in ways that suited American interests and aspirations go back decades. For the American Beltway elite, the issue of China was one of whether to change, contain or conquer; and its posture towards the rest of Asia revolved around the question of how this would shape its ability to contain China itself. The status of the island of Taiwan would feature prominently in this set of fluid calculations, and continues to play an important role in American calculus today.

From a purely geopolitical and force projection point of view, the island featured in US planning well before the end of World War 2, and certainly before the escape to Taiwan island by the defeated Republic of China-Kuomintang (ROC / KMT) forces in 1949 and 1950.

In the early 1940s the US State Department and Department of Defence began considering the future of Taiwan island, and America’s role. By mid-year 1942, the KMT made clear their expectation that Taiwan island would be returned to ROC (Chinese) sovereignty post-war. The then director of the Eastern Asiatic Affairs Department of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Dr Yan Yun-chu, made clear that the return of Taiwan island was appropriate as its population was largely Chinese and that, over time, the island had maintained close connections to the Chinese mainland. Within a year, this privately expressed sentiment was being amplified publicly, perhaps as a response to suggestions being made in the American media that Taiwan island should be placed under an “international mandate”.

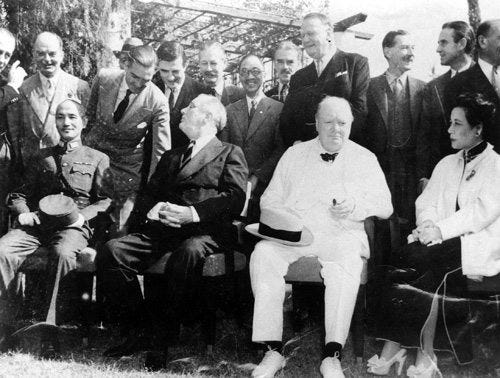

The Cairo Declaration in effect confirmed that the island would be returned to ROC jurisdiction. That said, the US preferred a US-led military administration with delayed handover of full sovereignty. Put plainly, the KMT was not well regarded by the Americans at the time. During the course of the second world war, the US had formulated both a plan of conquest and a plan of occupation for Taiwan island. While neither of these plans materialised, the planning showed just how significant an asset the island was strategically. The island was considered to be a critical military asset, no doubt, and while plans were drawn up to attack the Japanese bases on Taiwan, American agencies were also considering the challenges of future occupation of the island. By the middle of 1944, arrangements were put into place to train personnel specifically in anticipation of a planned occupation of the island. The US Navy was mandated to plan and administer the civil affairs of the island during the planned occupation, though it was the army that was expected to provide the majority of the personnel. Training of these personnel at Princeton University was scheduled to begin October 1, 1944.

While this planning and preparation was taking place, in the Spring (northern hemisphere) of 1944 news reached Washington that the KMT had formed a provisional government for Taiwan in Chungking (Chongqing) and were preparing to administer the island as a separate province. While the US did not expect the KMT to establish any form of government prior to the planned US occupation, there was sufficient concern amongst American policy makers as to the need to ensure US preeminence. The Americans did not believe the Chinese, under the leadership of the KMT, had the military wherewithal to force the surrender of the Japanese; nor was it believed that the KMT was well-equipped to administer the island upon the collapse of the Japanese. While the transfer of sovereignty of the island - as per the Cairo Declaration - was never disputed, there were debates about exactly how and when such a transfer would be made.

The State Department and the Department of Defence were at odds with each other as to whether the planned American occupation of the island should be fronted by the KMT at all. While input and advice from the Chinese was seen as politically necessary, the Americans were at pains to “prevent unwelcome participation or interference by the Chinese” and declared that “strict insistence on the exclusive responsibility and authority of the American military authorities be maintained” (US Department of State Records, quoted in Leonard Gordon (1968) ‘American Planning for Taiwan, 1942-1945’ in Pacific Historical Review). (The account above draws heavily from Gordon’s paper.)

The military strategic significance of the island was amplified in the post-war years as the US sought to consolidate America's Lake - namely, the greater Pacific Ocean - and mitigate risks of the USSR posing a threat to American primacy in the Pacific and its foothold in other parts of Asia, such as Korea. This was evident in Presidential level discussions entertained about the situation in Korea in June 1950. A classified memo, prepared by General Douglas McArthur, was circulated as part of this meeting, which described Formosa (the island of Taiwan) as an “unsinkable aircraft carrier and submarine tender”. Should the island fall into the hands of the Soviets, the memo went on to argue, “Russia will have acquired an additional “fleet” which will have been obtained and can be maintained at an incomparably lower cost to the Soviets than could its equivalent of ten or twenty aircraft carriers with their supporting forces.” Control of Taiwan island was, in this context, a critical bulwark to thwart Soviet risks in the Asia Pacific.

Fifteen years after McArthur’s memo, in another memo to US President Lyndon B. Johnson dated November 3, 1965, then Secretary of State Robert McNamara described the American posture towards the war in Vietnam in the context of a wider strategic frame aimed at the containment of China. This frame was premised on a fear that China would become a direct threat to America’s security. McNamara argued:

“The long-run US policy is based upon an instinctive understanding in our country that the peoples and resources of Asia could be effectively mobilized against us by China or by a Chinese coalition and that the potential weight of such a coalition could throw us on the defensive and threaten our security.”

He argued that China “looms as a major power threatening to undercut our importance and effectiveness in the world and, more remotely but more menacingly, to organise all of Asia against us.” The memo could have been written today!

The memo went out to outline a range of military strategic vectors that could be exploited to contain China without provoking a ‘hot response’ from either China or the Soviet Union. This memorandum was emblematic of a wider attitude in the American political establishment about the situation in Asia at the time, and which has, to large extents, continued to shape the parameters of assessment of American interests and concerns in the region today.

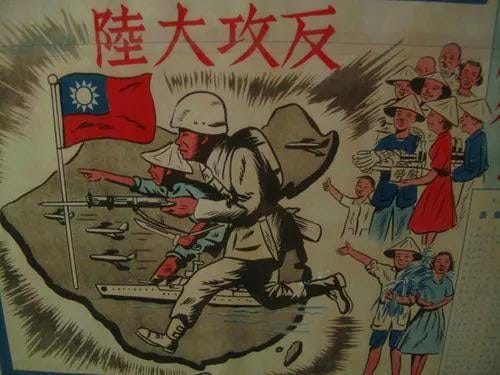

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, with the US ensnared in the conflicts in Indochina, the Americans had little capacity to accede to Chiang Kai-shek’s efforts to gain American assistance to mount his various invasion and reclamation plans in relation to the Chinese mainland. It has generally been recognised by historians that these overtures were rebuffed; the US had its hands full elsewhere and were not supportive of opening another front. Despite the reticence of the US, upon the onset of the Cultural Revolution (1966), Chiang Kai-shek was adamant that conditions for an invasion of the mainland were propitious. Chiang was readying for a deteriorating situation on the mainland, believing that instability would undermine the CPC regime. He reached out again to the US for support; again, it was rebuffed. The U.S. had its hands full in other parts of Asia, and some in the political elite were already contemplating a major realpolitik move to switch from the Republic of China to the People’s Republic of China as part of a wider effort to outflank and isolate the Soviet Union.

As much as there remained ROC / anti-communist diehards in the U.S., their influence at the time was constrained by pressures elsewhere in the Cold War. The diehards would have to wait for another day.

By 1969, the explicitly offensive posture that framed Chiang’s strategy since 1949 had given way to a combined ‘Unity of the Offensive and Defence' strategic position. This more ambiguous posture was eventually replaced with an explicit defence posture, after the establishment of the Guidelines for National Unification in 1991. At this time, the ROC effectively abandoned the strategy of retaking the mainland with military force, as argued by Takayuki Igarashi in a 2021 research paper. Of course, by then, the ROC had long lost formal American recognition, and that of the United Nations.

Realpolitik intervened in America’s posture towards the ROC in the late 1960s, culminating in the moves towards formal recognition of the PRC instead of the ROC. Kissinger and Nixon’s storied visits are well known, as is the fact that the opening up of dialogue with Beijing was driven largely by a strategic desire to gain leverage over the USSR. Kissinger articulated the underlying strategic thinking in an interview in Time Magazine in December 1970. He noted that the Soviets were interested in a dialogue with the US to reduce distractions on the “western front” so that they could address the Sino-Soviet border conflict in the east. Merely by letting Moscow know that the U.S. was “restudying the China question” the U.S. was able to secure considerable leverage vis-a-vis the Soviets. The dialogue with Beijing was, in the first instance, envisaged to act as a counterweight to the USSR.

Spiritual War & The Loss of China

The defeat of the KMT by the CPC was not only a geopolitical bodyblow to the U.S., it was also a metaphysical kick in the guts. The “loss of China” to the Communists opened domestic political scabs as the Truman administration was pilloried for its ineptitude in the years after the end of World War 2.

From the late 1800s and well into the first quarter of the 20th century, American Christian Missionaries trained their sights on China’s population as one of two remaining targets for salvation. The influx of missionaries to China was bound up with a neo-colonial missionary project that extended from civil religious nations of America as a saviour nation. This mission aimed at overcoming the last vestiges or strongholds of demonic power in what, as described by Rene Holvast (2009), was known as the 10/40 Horizon - the space between the 10th and 40th parallels where Christianity was yet to take a foothold and was at its weakest. The 10/40 Horizon covered North Africa, the Middle East, India, China and Japan. This missionary zeal saw a rapid expansion of the presence of missionaries in China until the 1940s. By the early 1950s, however, after the founding of the PRC, some missionaries concluded that it was no longer viable to stay in China and in due course Christian missionaries were prohibited in China at large and expelled. Those that did not return to their home countries found their way to the island of Taiwan with the retreating KMT forces or to Hong Kong.

The Christian missionary dimension of America’s commitment to Taiwan was embodied by the fact that Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and his wife were baptised in the 1920s, and were seen, by a rising American Senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, to be “fighting our war”. In castigating John H. Service’s capitulation to the communists - as part of a wide ranging speech on communists in the US State Department - McCarthy observed in a 1950 speech that,

“When Chiang Kai-shek was fighting our war, the State Department had in China a young man named John S. Service. His task, obviously, was not to work for the communization of China. Strangely, however, he sent official reports back to the State Department urging that we torpedo our ally Chiang Kai-shek and stating, in effect, that communism was the best hope of China.” (Emphasis added)

McCarthy had begun his fabled mission to expose communist influences in the US. The intersection between his anti-communist crusade and the dynamics of the war over China ultimately dovetailed with the great American lament that China “was lost”. The 1950s saw a virulent politicisation of the defeat of the KMT by the Communists in American electoral politics, which framed America’s interests not only in geopolitical terms (anti-communism) but in spiritual terms. McCarthy argued in that same speech that,

“Today we are engaged in a final, all-out battle between Communistic atheism and Christianity. The modern champions of Communism have selected this as the time. And, ladies and gentlemen, the chips are down– they are truly down.”

The chips were down because of treachery. The “loss of China” was both a domestic problem - traitors in our midst - and a worldly blow: Christianity on one side and Communistic atheism on the other. These Millenarian eschatological undertones, mixed with the zealotry of Manichean certainty, would animate an intense spiritual war as part of the wider Cold War environment. The spiritual war took spacial shape via the 40/10 frame, which defined regions of the world in which evangelical Christianity was thought to be underrepresented and weak. Conversely, therefore, these regions of the world - which included China - were the dominion or strongholds of powerful demonic forces. Such forces had to be dethroned to enable evangelisation to take place, ideally before the year 2000 (see O’Donnell). The territorialisation of the spiritual war buttressed the geopolitical-cum-ideological predilections of the time, forming a powerful concentration of forces that continue to play critical roles in American attitudes toward China (and the island of Taiwan) today. For ardent evangelicals, territorial conversion presaged the building of God’s kingdom on earth and laid the groundwork for the climax of Christ’s return.

Taiwan island figured strongly in this territorial-spiritual configuration. In a speech delivered in the US to a Christian Congregation in early 1958, by a former ROC Ambassador to Japan, the question was posed: “what can Christians in America do for China?” He was there seeking to rally American Christian support for the ROC in its ongoing efforts - at the time, as noted earlier - to retake the mainland. He intoned:

“Communist China, in its diabolical endeavor to uproot true Christianity, has wiped out in less than a decade the missionary work done by Western Christians during the last one hundred years. It has hounded and driven from China the dedicated American men and women who have devoted their lives to foreign missions.”

He quoted favourable the words of an (unnamed) American missionary who had, in 1957, claimed:

“True Christianity cannot do business with the stooges of the Communists, or be a party to the Communist use of the church for propaganda purposes... The line against Red China must be held. We must work and pray for the liberation of Red China and the opening of the doors again for missionaries.” (Emphasis added)

The politics was no ordinary politics; it was fundamentally one of a spiritual war. He argued that America’s interests, insofar as they are the interests of Christian missionaries, was to enable the recapture of the mainland by supporting the forces at work on the island of Taiwan. He thus argued that:

“Fortunately, while the Christian church stands in ruins in mainland China, it is surviving strong and confident in the province of Taiwan, which is now the seat of the Government of the Republic of China. The years of separation from the mainland have seen the Christian church in Taiwan advancing by leaps and bounds.”

Taiwan was clearly seen as a remnant of better days, but also a sign of better days in the future. In the decade since the communist victory, and the purge of missionaries from the mainland, the “province of Taiwan” was a refuge in which Christianity could develop and flourish. To illustrate just how much Christianity had flourished on the island, he provided some statistics. He tells his listeners that:

“In 1945, when Taiwan was returned to China after a half century of Japanese rule, there were less than 30,000 Christians on the island. Only a few denominations were allowed to operate, the most active being the Canadian Presbyterian Mission. Today, over 100 Christian denominations are operating in Taiwan. Within the space of 12 years, Christian membership has increased from 30,000 to nearly ten times that number.”

He evidenced a 10-fold expansion of the Christian congregation on the island in the mere space of 12 years. Note, incidentally, his recognition that Taiwan was returned to China by the Japanese at the conclusion of the second world war.

For him, Taiwan was a Christian beacon. He would describe an “average Sunday” in the Shih Ling Church that he would attend in Taipei, where:

“… you will see in the pews such prominent persons as President and Madame Chiang Kai-shek, Prime Minister and Mrs. O. K. Yui, Chief Justice Wang Chung-hui and his wife, Secretary General to the President and Mrs. Chang Chun, Chief of the Combined Service Forces and Mrs. J. L. Huang, and others high in the political life of the Republic. There is no country in Asia today where more outstanding government leaders are active Christians than in the Republic of China.” (Emphasis added)

He explicitly linked the propriety of the Government with its spiritual orientation, and pointedly observed that Chiang Kai-shek and his wife were prominent participating parishioners. Taiwan was a spiritual bastion, and a platform from which the Christian mission could again be launched to reassert the missionary presence on the mainland. The anti-communist battle was also a Christian rallying cry. Taiwan was not just an unsinkable carrier to be kept out of Soviet hands; it was the hole in the wall from which the spiritual war in China could again be prosecuted.

Engagement: same aims, different means

Engagement has been the most recent manifestation of how American aspirations were to be pursued, in the hope that entanglement with the American global order after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 - the putatively named ‘rules based order’ - underpinned by the economics of the Washington Consensus, would ultimately catalyse political and cultural change in China.

Prior to the recent couple of decades of engagement, the American posture towards the People’s Republic of China was shaped by periodic contingencies, such as Kissinger and Nixon’s aims to outflank the Soviet Union, and prior to that concerns about the spread of communism throughout Asia in the decades immediately following World War II. In those decades, America’s China policy was framed by a deep-sense of grief - who “lost China” was the acerbic question posed in the early 1950s.

The “loss of China” animated American domestic politics throughout the 1950s, within the context of a rampant McCarthyism and the emergence of a spiritual war mentality as part of the wider Cold War context. The ambition was to redress this “loss”, utilising the island of Taiwan as a bulwark against communist dominoes and, potentially, as a launch pad for military action directed at the Chinese mainland. The island served as both a geopolitical ‘unsinkable carrier’ and as a holding ground for the spiritual army of missionaries who’d retreated to the island in the late 1940s and 1950s.

China was to be regained, if not by force, then through the efforts of missionary work. Whether it was Christianity, or failing that, the confessional of neoliberal economics, the aim was to liberate the Chinese souls from the illiberal and godless shackles of Marxism-Leninism. These transformation efforts - to “shape or change” - have foundered in the face of what Campbell and Ratner describe as Chinese defiance.

Back to Containment

The American political establishment’s reaction has been to abandon the tactics of engagement. In its place, a dormant and visceral animus towards China has now been unleashed, amplified by the $1.6 billion congressional appropriation for anti-Chinese propaganda (September 2024), drawing from this deep well of thwarted ambition coupled with the impulses of millenarian exceptionalism. Disengagement via economic sanctions and assorted prohibitions; the pursuit of Chinese ‘spies’ in the American education and research institutions; and the growing ambivalence towards trying to understand China, as recently observed by Li Cheng (Financial Times, October 25, 2024), all evince a political culture convinced of its own exceptionalism and incensed at China’s refusal to yield.

Sanctions and tariffs are likely to intensify. Trump has made clear his predilections towards tariffs as an instrument of foreign policy, and confidante Robert Lighthizer - author of No Trade is Free - is already at work persuading lawmakers that intensified tariffs are necessary to thwart China and rejuvenate American industry. Lighthizer is advocating for a concerted effort to effect an economic decoupling from China, to weaken China and strengthen America in one move. For Lighthizer, China poses an existential threat to the United States and must be aggressively dealt with.

Others are pushing even harder. In May / June 2024, Matt Pottinger and Mike Gallagher argued in a piece in Foreign Policy that the Biden administration was excessively focused on short-term tactical questions revolving around the notion of “managed competition” when, in fact, the question was a complete victory over China. For Pottinger and Gallagher, a former Deputy National Security Advisor in the first Trump Administration and a Congressman and Chair of the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party respectively, that meant the pursuit of a strategy of regime change. America’s China was lost once, and it had to be remade.

Trump’s tenor and the mood of the Beltway milieu aren’t discordant. In part, Trump's own perspectives contribute to the mood, and the mood reverberates through the political parameters that shape the dynamics of how the Executive branch navigates the legislative branch. They are symbiotic, rather than at loggerheads.

The mood inside the Beltway is one of loathing and belligerence. China is blamed for America’s domestic woes, and represents a challenge to America’s sense of its global standing. Communist China is an existential threat to the United States, according to the Beltway milieu. For decades, the US sought to shape and change China into its own image; to reclaim a China lost to the Communists. That China refused to yield should have been the object lesson for the need for what Heer describes as “reciprocal compromise”. But Washington was never about compromise. Its millenarian zealotry and a re-animated spiritual war forbids that.

Can Trump step outside of the milieu and reshape its mood, or will the milieu find effect through a Trump presidency? That is the question of our times.