Supply Chain Disintermediation: Another Unintended Consequence of Trump’s Tariffs

Retailers, watch out!

Since the US Administration launched the ‘reciprocal tariffs’ on 2 April 2025, and embarked on a tit-for-tat tariff war with China, Chinese OEM firms have taken to social media, showing that most high-price branded goods are actually made in Chinese factories, and consumers are footing a bill that is substantially higher than factory revenues. OEM stands for Original Equipment Manufacturer. OEMs are contracted manufacturers, creating final products for others and sold under the brand of others.

Many well-known western brands across diverse product categories are manufactured by OEMs. Some brands can be considered to be mainstream (non-luxury) brands, whereas others are the luxury brands that have commanded high prices. Luxury goods have what economists call ‘Veblen characteristics’, in that the price elasticity of demand is often negative; as the price rises, so too does demand. Perceived scarcity or exclusivity are key features of Veblen goods.

The point about both mainstream brands and Veblen goods is that they generate revenues for brand owners that are in large part what can be described as ‘brand premium rents’. Let’s say that the final price paid for a product represents the ‘whole of supply chain monetary value’ of a good; for a supply chain to function effectively and reproduce itself, that value must be distributed throughout the functions of the supply chain, enabling each function to repeat itself through the next production and circulation cycle.

Complex supply chains involve the coordination of physical processes and resources across multiple sites, through a series of events, so that a product can be produced, shipped to market and ultimately sold and used / consumed. Between the original manufacturer and the end user may be numerous functions fulfilled by a disparate array of supply chain actors. These include transporters, storage providers, wholesalers and retailers. Not only do each of these fulfill various functions, they also can play important roles in the circulation of money capital throughout the process. Wholesalers and retailers have, for instance, historically also functioned as finance intermediaries or aggregators, purchasing goods in bulk from upstream suppliers at a discount and then storing these goods, marketing them and ultimately selling them at a mark-up.

Supply Chain Value

Trump’s tariffs and the social media aftermath from OEMs have revealed important features of contemporary supply chain networks, which are now ripe for significant disruption. In short, new pressures will emerge compelling supply chains to become shorter (meaning, reducing the number of agents making claims on the ‘whole of chain value’).

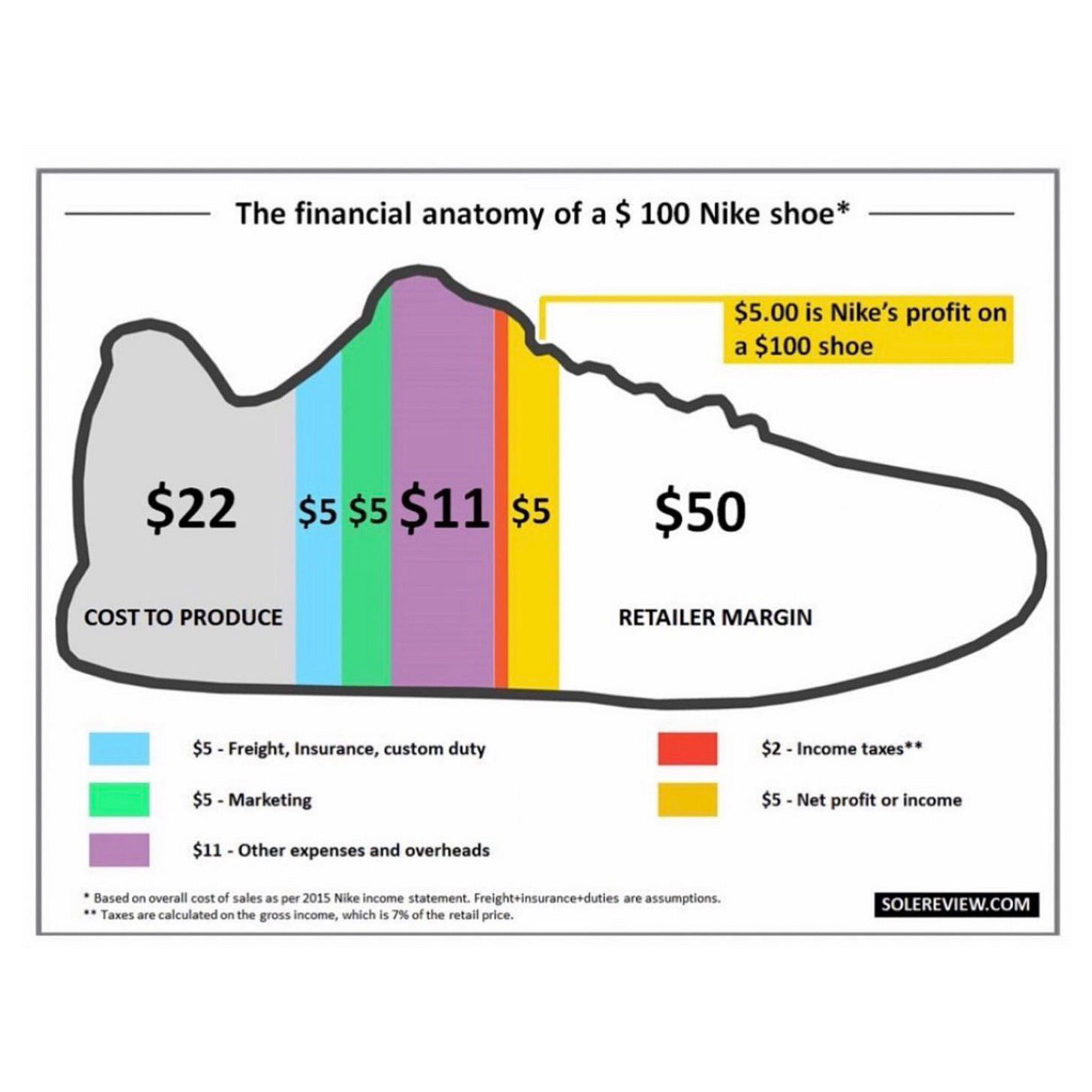

The breakdown of claims varies from product type to product type. However, it is worth examining the case of a pair of running shoes - nicely examined by Solereview.com - as it allows us to explore the issues and dynamics involved. According to Solereview, brand owners sell shoes to downstream retailers at approximately 50% the final retail price. Thus, we get the following basic breakdown, for a pair of shoes with a landed cost of $24.30:

Factory production cost $20.00

Shipping $1.00

Insurance $0.30

US Customs $3.00

The brand-owner sells this to the retailer for $50.00, earning a gross margin of $25.70. (Note, from this comes expenses such as company operations.) The retailer sells the shoe for $100.00.

As supply chains come under pressure from tariffs, brand owners are driven to seek to increase margins. With the possibility of direct-to-consumer operations, brand owners could well look to bypass the retailer and deal directly with the public. Operational changes would need to be considered, including running their own storage and logistics / fulfillment functions. However, it is conceivable that bypassing the retailer can deliver a better gross margin to the brand owner than the current model.

The pressure to do this comes from the fact the consumers themselves could consider opportunities for direct-to-factory channels. OEM manufacturers are incentivised to consider this approach to enhance their potential share of the ‘shoe spend’. Customisation of products is increasingly possible through various Chinese platforms, which connect directly to OEMs. Brand rents are as a result under pressure.

The same dynamic applies to luxury brands too, though market feedback suggests that wholesale gross margins are considerably higher for luxury brands than for more standardised branded products. The price to cost ratio could be as high as 10 or even 20:1.

Amazon

The kinds of impacts considered above can have serious implications for online e-commerce platforms that have built business models around products that originate from China. Amazon is a case in point. Recent data (around late 2024 to early 2025) suggest that about 40% to 50% of products sold on Amazon U.S. are estimated to originate from China. Around 40% of the top-selling merchants on Amazon U.S. are Chinese sellers directly (i.e., based in China). In addition, many U.S.-based sellers (and sellers from other countries) source their products from China, especially private label products and generic goods manufactured cheaply. Combined, the actual share of products made in China could be well over 60%.

From around 2015, Amazon actively recruited Chinese manufacturers to sell directly on its marketplace. By 2023, Amazon began trying to diversify sourcing (e.g., from Vietnam, India and Mexico), but Chinese suppliers remained dominant. Products like electronics, home goods, clothing, toys, and many private-label brands are heavily Chinese-sourced.

If Chinese-made products were no longer available, as a result of exorbitant tariffs, the impact on Amazon could be quite severe. Amazon had a total net revenue for 2023 of ~$575 billion. Online store sales accounted for ~$220 billion with third party seller services bringing in ~$140 billion. The remainder of revenue came via other services such as AWS, advertising, subscriptions etc. Online store sales and third-party seller services are directly exposed to the impact of tariffs and the loss of Chinese goods. Assuming that about 60% of goods sold on Amazon originate from China (both direct and indirect sourcing), this means that ~$132 billion of Amazon’s total product-related revenue (i.e., 60% x $220 billion) is dependent on China-originated products.

Assume that all China-originated products cease trading as a result of tariffs. We can undertake a ‘back of envelope’ estimate of impacts on Amazon’s revenues. For online store sales the impact would be as noted ~$132 billion. Add seller fees associated with third party sellers of China-sourced products; here, we assume that 60% of third party seller services revenues are China-related, so we can estimate the impact to be 60% x $140 billion, which is another $84 billion. In total, the direct annualised revenue impact would be in the order of $216 billion. This is a little over ⅓ of Amazon’s annual revenue.

There will be flow-on impacts too. These could include a slowdown in fulfillment and logistics resulting in lower volumes and higher unit costs and reduced advertising revenues with fewer sellers spending less on advertising. Reduced inventory could drive away customers, who seek alternatives directly from factories with lower pass-through costs.

The Canary in the Coal Mine

The admittedly rather rough case study of Amazon does nonetheless point to the risk of severe implications for American retailing. In some respects, Amazon - and Walmart as well, which depends on Chinese supplies for about 60% of its inventory - is a canary in the coal mine. A sudden or enforced decoupling from Chinese supply chains could have far-reaching, cascading effects across the entire US economy.

This is because the impacts relate not only to finished goods but also to the supply chains of intermediate goods. Chinese manufacturers are deeply embedded in the global supply chain network. Alternative suppliers in other countries rely on Chinese inputs themselves. Domestic American production capacity for many consumer and industrial products has atrophied over the years, and would take many years to rebuild - if in fact they ever could be. There is no quick replacement, which means U.S. consumers and businesses would face immediate price shocks, shortages, and quality variability.

In the US, there are about 1 million businesses involved in retailing (general retailing, e-commerce, electronics and fashion). A further ~730,000 firms are in wholesale trade as importers and distributors. There are tens, if not hundreds, of thousands American manufacturers that use Chinese-supplied parts and materials in their own production processes. In addition to these enterprises directly affected by Chinese supply chain disruptions, indirect impacts can also be expected in areas such as logistics, warehousing and freight; software services as demand for SaaS and analytical tools declines; customer service and support, and firms involved in marketing and advertising.

Some 16 million Americans are employed in retailing and related sectors, representing 10% of the working population and 6% of GDP. Significant job losses could result. At the same time, rising costs and product shortages are likely creating the conditions for not only a recession but stagflation - namely, reduced output with inflation.

Global Value Chain Reconfiguration

An unintended consequence of Trump’s tariffs could well be a tectonic shift in global value chain value distribution and capture. For years, Chinese manufacturers have been the silent backbone behind major Western brands (Apple, Nike, GE, even luxury brands). They’ve delivered production services a white-label or OEM providers. Now, they are saying to the global consuming public: “You’re paying $100 for that product; we made it for $24”. Platforms like AliExpress, Temu, Shein, Alibaba (via DTC integrations), and TikTok Shop are helping them go direct to global consumers — disintermediated without middlemen, with the destruction of ‘brand premium rents’.

Retailers like Walmart, Target, Best Buy and even Amazon implement substantial mark-ups on Chinese-made goods, often exceeding 100%. The introduction of tariffs catalyses a rethink of this model, particularly as households continue to feel the pinch of inflation. Price sensitivity rises and brand loyalty fades. Consumers will become more willing to wait a little longer for cheaper, direct shipments and even take ‘risks’ on unknown brands or products without brands. Here, retailers are being disintermediated and brands lose control of the value capture process. Retailers are at great risk of margin compression, rising inventory costs and the erosion of brand relationships.

Of course, brands are aware of their vulnerabilities to these dynamics. So many are being compelled to respond too, and are cutting out retailers by building their own online stores, driving their own influencer-driven sales campaigners, partnering with factories to share margins and also creating their own parallel private-label supply chains. If factories can sell directly to consumers, we had better do it before they eat our lunch. Consumers are empowered to make this shift to direct procurement; AI overcomes language barriers and cross-border payments models and services are increasingly seamless. Product tear-down reviews and video demonstrations help consumers make informed decisions and ready-to-hand price comparisons drive competition.

We may well be on the verge of a collapse of the traditional value chain pyramid that has dominated the American economic landscape for decades. The traditional model saw a multilayered supply chain network link factories to consumers via OEM brand owners, wholesalers and retailers. This is giving way to more streamlined models in which factories either roll out their own platforms (or work with existing platforms) to reach consumers directly, or work tightly with brands to reach consumers directly.

Before Trump’s tariffs, American OEMs and brands were perfectly content to outsource everything from design-for-manufacturing to tooling, to final assembly, to China. The strategic and value trade-off was clear: “Let Chinese firms do the hard, low-margin work, and we’ll capture brand value, IP rents, and global consumer markets.” This worked for decades, until it didn’t.

Trump’s first wave of tariffs in 2018-19 disrupted this set of quiet interdependent relationships. Chinese manufacturers were forced into the spotlight. They started to advertise their capabilities to the world. The ‘hidden secret’ of Chinese OEM capability was no longer a secret. Many began to pivot into direct-to-consumer brands, especially on Amazon and now TikTok. At the same time, supply chains became increasingly politicised. Attempts were made to force through decoupling from Chinese supply chain networks, but with limited success. Alternative locations continued to struggle to match the scale, speed, price and sophistication of Chinese manufacturing. Attempts at reshoring were hampered due to cost barriers and lack of sufficient resources.

Talk of rejuvenation of manufacturing is easy, but the walk is much tougher. Factories are more than just machines and workers. They are embedded operational nodes in complex networks, or ecosystems, including subcontractors, component suppliers, packaging providers and the like. They are also sophisticated engineering systems coupled with ever-deepening IT systems that drive speed, responsiveness and optimal efficiencies in production, inventory and distribution. Chinese manufacturing prowess has continued to improve because there are built-in learning-by-doing effects. These tacit knowledges are simply not readily portable or replaceable.

China as a whole is strongly positioned to weather this present trade war storm. It has the factories, which means it controls production. By controlling production, it is able to manage the downstream supply chain systems that take products to buyers. Trump 1.0 and now Trump 2.0 is ushering in an era of supply chain disruption, but not in the way that was anticipated when policy-makers in Washington began talking about ‘bringing back manufacturing’. Manufacturing won’t be coming back to the United States any time soon in any great quantity. But the supply chain disintermediation sparked by the introduction of tariffs will now affect both the upstream sources of American economic value (namely in design, brand ownership and IP rents) and the downstream systems of retailing.

An exemplary analysis — you performed a case study analysis such as we did at business school — from which gross and pretax margins can be clearly seen on a typical China manufacture for the US retail market.

Kevin Walmsley pointed on some time ago that this structure could provide enormous returns to European car companies if they were to partner with Chinese ev manufacturers — as the in country dealership and service profits would be substantial.

The fundamental fact is that China has almost priced its export (wholesale) costs at very small gross margins. If you see the aggregate figures for the value in USD of rare earth exports over the last decade, you would be shocked. As shocked as we are today to think no one in the west tried to stockpile.

The competition between Chinese companies has resulted in an almost pathological inability to price its goods properly (to ensure adequate profits to Chinese workers and companies). Louis-Vincent Gave has talked about this. Chinese companies are so willing to commit seppuku that China is actually the country with the problem that Trump lays claim to: victimization.

Great article, thanks. What America is doing is basically like a household refusing to go to their local supermarket, electric store, hardware store after deciding that it's cheaper to grow their own food, make their own clothes, build, design their own smartphone and smart TV, manufacture and design the countless bits and pieces a household needs, all while at the same time working to pay off a massive mortgage, pay for ever increasing fuel, electricity and education. Oh, and don't forget that there isn't one person in the household who has the skills, never mind the materials to make this independence from the store possible.

Do you think that the policy makers in Washington are on drugs?

Maybe these idiots are watching too many survivalist videos on yt while lighting up the crack pipe.

Do you have another explanation for this madness?