Sovereignty and Regional Soft Power in Doubt

Questions about Australia's unresolved identity in the 21st century

Australia’s standing in the Asia Pacific region - what some call its ‘soft power’ - is at risk of diminishing as the public debate in the country on AUKUS and the nation’s stance on Palestine intensifies. America’s Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell’s recent impromptu exchange with Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, about Australia’s policing agreement with Pacific Island nations, when he said “we’ve given you the lane, take it” further animated questions about Australian sovereignty and raises doubts as to whose interests it serves in the region.

While the political establishment has exhibited bipartisan unanimity on Australia's commitment to AUKUS and Israel, dissenting voices on both core issues have increasingly aired.

Australia’s identity is again being examined ‘from the inside’, just as the region is reflecting on its own future in a world of shifting geopolitical sands. In this context, as Asian nations forge their own sense of identity and regional sovereignty, Australia risks alienating itself from its region as it favours history and culture over geography. Put plainly, Australia runs the risk of reinforcing its historical status as an extension of western colonial power seeking security from Asia, rather than participating in and contributing to security in Asia.

Soft power fading

Various soft power measures suggest a decline in Australia’s standing. According to the Brand Finance Global Soft Power Index, Australia’s standing has progressively declined from 6th in 2015 to 10th in 2019 and 14th by 2023. If this is the global pattern, the decline is mirrored in the fall in Australia’s overall trust levels in Southeast Asia. According to Edelman’s Trust Barometer, Australia was consistently one of the lowest performing countries landing in the ‘distrust’ range with low scores of between 1-49 out of 100. Australian media is not trusted, with a score of 40 out of 100 and trust in government remains neutral at best. Concerns about declining soft power in the Asia Pacific region have concerned many in Canberra for a number of years. Various efforts and funding commitments to initiatives such as educational exchanges have clearly not had any substantial effect, given that Australia’s soft power ranks have been consistently in decline.

Despite the various ailments about declining soft power, little has been done to arrest the slide. A review of ‘soft power’ launched in 2018 by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade was ultimately aborted by the time the new Albanese government came to office in 2021. Problems with conceptualising ‘soft power’, let alone ‘measuring it’ have plagued efforts to address questions of non-military influence, as lamented by then DFAT Secretary Frances Adamson in testimony to a Senate Estimates Committee in 2020. DFAT’s organisational chart dropped any reference to ‘soft power’, perhaps as a clear sign of an inability to action what couldn’t be measured. As for hard non-military measures, we can also see that the limited diplomatic footprint of Australia underpins the fragility of Australia’s regional influence, as made clear in the Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index.

Australia’s standing in Asia remains a dilemma for a country that confronts geographical realities and historical colonial legacies. In a recent survey of Indonesians, the Lowy Institute found that trust in Australia had declined from 75% in 2011 to 55% in 2022. This trend parallels Indonesians’ declining trust in the USA. Across Asia more generally, public reception of the US has been on the decline, coupled with a relative rise in positive attitudes towards China. Australia’ clear proximity to the US on foreign and defence policy issues is likely to see relative ambivalence to negative attitudes towards the US rub off on those directed towards Australia.

Whatever ‘soft power’ is understood to be from an Australian point of view, it was and remains something that the national government is struggling to address.

AUKUS - a faltering fait accompli?

If so-called soft power status is on the wane, one is left to wonder whether and how ‘hard power’ manoeuvres have or could impact dynamics. AUKUS is the most obvious of the turns to ‘hard power’.

Three years ago, on 21 September 2021, AUKUS was ushered in by the Morrison Government as a signature agreement to anchor Australia’s future regional security commitments. In many ways, it could be seen as a bookend to a decade’s long process of intensified integration of Australia within the US’ wider regional military strategies and ambitions. The abandonment of Australia’s previous contract to procure French-made conventional submarines in favour of nuclear powered submarines from the UK-US stables is the centrepiece of AUKUS. The headline cost of US$368 billion has, unsurprisingly, drawn much attention, as it points to this decision being Australia's most costly defence decision ever.

Morrison deftly cornered the then Labor Opposition led by Anthony Albanese, giving the Labor leadership about seven hours to decide whether they would back AUKUS or not. In the lead-up to a national election, Labor’s calculus was that it could ill-afford to be painted as being ‘weak’ on questions of national defence, let alone accused of being ‘soft’ on China. In any case, the ALP has - bar for a small number of exceptions - long-cherished the Australia-US alliance and many within the parliamentary party were active champions of Australia’s role as an American regional defence / security alliance partner. Labor Prime Minister Julia Gillard, back in December 2011, agreed to enable an expansion of US troop rotations through Darwin, in Australia’s north. This agreement laid the groundwork for increased US military presence in Australia. Indeed, as the Australian Financial Review observed (30 July 2023), the “permanent American military presence on Australian soil is now at a scale unprecedented since the Second World War. And it is accelerating.” Australia was being set up as what the Washington Post described as a “launch pad” for American military interventions in the Asia Pacific, as US military stockpiles were being built up.

As recently documented by Andrew Fowler in his book, Nuked: The Submarine Fiasco that Sank Australia’s Sovereignty, the Americans were vexed that Australia appeared to be edging towards a security arrangement with France outside of the orbit of American influence, and moved assertively to undermine that possibility. Morrison was susceptible to American overtures, as was the Labor Opposition. Fowler is scathing of Morrison, arguing that:

“the huge shift in Australia’s foreign policy alignment was hatched by a Christian fundamentalist former tourism marketing manager with no training in strategic or foreign affairs but a great gift for secrecy and deception.”

In any case, at the time, AUKUS’ adoption by the Australian political and defence establishment was a fait accompli. The move arguably was an extension and deepening of the trend towards greater integration with American military planning for the Asia Pacific, with bipartisan support. Even if there were concerns from the Labor Opposition, the political calculus in the face of the upcoming election limited the party’s room to move.

At the time of its announcement, there was mooted criticism at best. One would be forgiven for thinking that AUKUS was a ‘lay down misere’. However, in the three years since, the chorus of critical reactions has grown. The public debate about AUKUS has been a slow-burn, as further details - or the lack of them - began to raise doubts about the merits of the decision.

Arguments have raged about whether AUKUS compromises Australian national sovereignty, and whether in fact the decision makes any defence strategic sense. Operationally, there are serious doubts as to US capacity to deliver on the submarines, rendering a strategic dependency on this hardware decision highly questionable in any case. Regionally, quiet concerns have been aired about the risk of nuclearising a nuclear-free Pacific. Some countries in Southeast Asia, Indonesia and Malaysia amongst them, have raised concerns that AUKUS could catalyse greater military tensions and instabilities in the region, rather than dampening such tensions down.

So far, the Australian government and opposition have doubled down on AUKUS, despite risking public concerns. Whether such public concerns ultimately impact government policy remains an open question though there remain powerful institutional reasons why a change of direction will be difficult to execute in the near future. In any case, Australia’s hardened commitment to an American-led Asia Pacific security framework - embodied by AUKUS - contributes to Asian nations’ unease about the implications for the region’s stability and, doubtless, casts doubts over Australia’s future role within Asian security and stability as well.

A Genocide in Gaza

If there is an issue that has caused an even greater cleavage between the countries of Southeast Asia in particular and Australia, it is the question of the genocide in Gaza. There’s no need to rehearse the sequence of events that have tragically unfolded in Gaza since October 2023 to note that Australia’s stance has been significantly at odds with the position that has been adopted by countries across the region.

Australia’s position has been characterised by prevarication and tardiness in the face of growing global concern and condemnation of Israeli actions. The institutional muscle memory of the Australian political establishment has been to align the country’s official position with that of the United States. In recent months, in the face of growing public anger about the refusal of the Australian government to condemn Israeli actions, the government has been compelled to moderate its heavily pro-Israeli position and it has begun making modestly critical comments about the need for a ceasefire. This modest adjustment to rhetoric does not obviate the possibility that Australia has singularly failed to uphold its international law obligations in relation to the Gaza genocide, but worse, that through the supply of components for military equipment has actually contributed to the genocide. Australia’s muted and belated verbal consternation about the genocide in Gaza places it at odds with the stance of many others in the Asia region.

Malaysia unequivocally condemns Israeli actions. Indonesia condemns Israel’s rejection of a two-state solution. ASEAN foreign ministers have similarly condemned Israeli aggression. Australia’s equivocation stands in stark contrast, and is unlikely to be missed by its Asian neighbours.

Deputy Sheriff in the Pacific

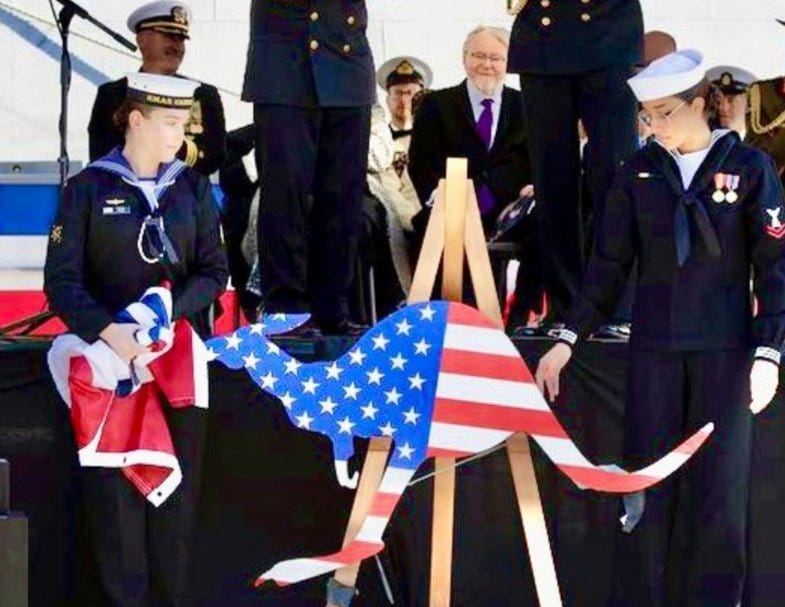

The extent of Australia’s sovereignty and ‘agency envelope’ was also recently brought into question at the conclusion of the Pacific Island Forum meeting, at which a new policing agreement between the Pacific Island nations and Australia was entered into. Australia’s Prime Minister Albanese was filmed by a New Zealand journalist advising American deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell of the agreement. Campbell was recorded as responding with praise, saying to Albanese, “we’ve given you the lane, so take the lane”.

This recent incident prompted former Australian ambassador Geoff Raby to pen a piece, pointedly observing that recent events serve to remind the world of Australia’s status as America’s ‘deputy sheriff’. Had Australia not acted, and secured the policing agreement, in all probability the Americans would have taken matters into their own hands. Campbell’s remarks to Albanese made it clear that the Americans had raised the matter with Australian ambassador to the US, Kevin Rudd, indicating that the Americans were inclined to act. Rudd assured Campbell that that would not be necessary.

The relationship between Australia and the Pacific Island nations has been a history tainted with colonial condescension and a big dose of what I’ve previously called “languid insouciance”. Australia has tended to act only when necessary, and even so, has usually left the Pacific deeply disappointed with the gap between the rhetoric of “family” and the reality of retarded development. The failure of western nations to act on climate change - an existential issue for the Pacific Island nations - adds insult to injury. Tuvalu’s Climate Minister has recently asserted that Australia’s approval of three new coal mines is akin to drowning the Pacific and a “direct threat to our collective future”.

In any case, despite the recent policing agreement, some Pacific Island leaders remain sceptical about the sincerity of the arrangements, concerned that the Islands may - against their wishes - be dragged, by Australia, into the maelstrom of major power competition and be used as a pawn.

A National Identity in crisis?

Australia’s soft power has been on the wane for the past decade, perhaps longer. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade was cognisant of this, and began to investigate the slide in 2018. By 2020, the investigation was wound up without any conclusions. Meanwhile, Australian policy priorities seemed to shift further away from whatever there was of its ‘soft power’ dimensions. Despite securing expanded extraterrestrial access to Australia via the Force Posture Agreement, the US had been concerned of Australia’s potential drift away, and moved decisively to curtail the submarine contract between France and Australia. AUKUS was the American-led replacement.

AUKUS was ushered in with barely a dissenting voice in September 2021. Three years later, however, critical voices have been growing led by former Prime Ministers, Foreign Ministers and assorted political and civic leaders. What was perhaps seen as a fait accompli when Morrison snookered Albanese to back the arrangement is now looking a little less certain. Just as domestic concerns have slowly emerged, so too have regional neighbours been alarmed by the prospect of increased regional instability as a result of the AUKUS agreement. The distance in outlooks between Australia and South East Asia has been put into sharp relief by the respective responses to the Gaza genocide. Asia’s most populous nations have consistently condemned the Israeli atrocities, attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure; at the same time, Australia - following Washington’s lead - has for much of the period since October 2023 disturbingly silent. Its recently concluded policing agreement with Pacific Island nations also smacks of the subordination of sovereignty as Australia “took the lane” given by the Americans.

Rather than being seen as a participant in, and contributor to regional security and stability, Australia runs the risk of being positioned squarely as a colonial interloper taking its marching orders from Washington. Recent talk of Australia “pooling sovereignty” with the US cements this perception. The AUKUS agreement has ripped open an historic sore, which has never fully healed. The political establishment’s tawdry failure to condemn Israel’s genocide poured salt into the wound. The policing deal in the Pacific highlighted Australia’s subordination to American priorities: “thanks for the lane, Kurt”.

What has emerged in the unfolding critical public reaction is a struggle not only for Australia’s identity; it’s also about Australia’s place in the world and its relationship with Asia. Can Australia transcend its historical constraints, and shed the shackles of anxiety (David Walker) and fear of abandonment (Gyngell) that have bookended its relationship to its region and its craven need for protection from one of the transatlantic powers? Can Australia find its place as an Asian nation, or will it become estranged from its geography as it finds comfort in the bosom of its cultural and colonial roots?

The political establishment has baked-in instincts and muscle memory. Decades of intermingling with the institutions of Washington have ensured that, as shown by, amongst others, Vince Scappatura in his The US Lobby and Australian Defence Policy. But increasingly, the public is looking askance at this apparent absolution of sovereignty and are demanding an Australia that is less ‘deputy sheriff’ and more an independent nation that needs neither Washington nor London for its marching order. As the 21st century unfolds, the unresolved question is whether Australia can find its way to jettisoning its anxieties and fears so as to become an Asian nation or remain as an intruder in Asia trying to “take its fair share” from the region.