Security in Asia or from Asia?

How tangled is Australia? The economy turns to China, the military moves closer to the United States

The U.S. is driven to reclaim primacy in Asia. This pursuit is anathema to ASEAN centrality as a key institutional organising principle of regional peace and prosperity. A strong and pivotal ASEAN is inconsistent with American Asian primacy, and vice versa. In its quest, the U.S. is mobilising subimperial allies, client states and former colonies by way of a network of minilateral agreements that challenge ASEAN multipolarity.

The AUSMIN consultations that took place this week in the U.S. between the American Secretary of State and Secretary of Defence and their Australian counterparts seek to affirm and align Australia’s subimperial interests and America’s Hegemonic ambitions. Australia’s subimperial reflex has seen it commit to American-framed strategic imperatives and associated operational initiatives for the region. The joint statement released on 7 August 2024 confirmed the US and Australia’s alignment on military matters. Military prerogatives are determined by the imperatives of the United States, with Australia continuing to play a subimperial role

.At the same time, however, Australia recognises that American primacy is no more. Indeed, Australia’s official posture is to recognise ASEAN centrality, yet in practical terms its commitment to U.S. led militarisation of the region threatens ASEAN centrality. Put plainly, the Australian government acknowledges and supports a multipolar regional order as a reality today, while at the same time delivers unconditional support for American military strategy in Asia. These two positions, as eminent Australian scholar Hugh White has observed, are incompatible.

These contradictions speak of unresolved questions in Australia about its relationship to the Asian region and its nation states, and what this ultimately means for Australia’s longer term security and prosperity. The issue was once posed by former Prime Minister Paul Keating (pictured) in words to the effect: does Australia seek its security in Asia or from Asia?

Anxious Nation and Fear of Abandonment

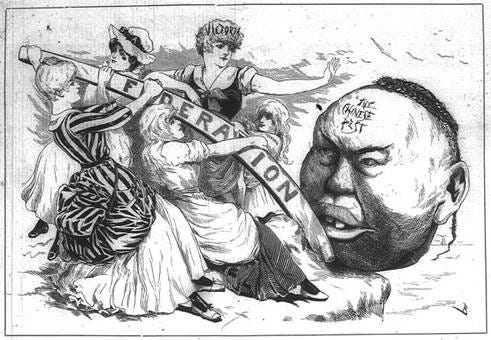

Modern Australia is a white colonial settler nation. Its relationship with Asia is marked by this historical cultural and racial imprint. In his analysis of Australia’s stance towards Asia in the late 1800s through to the early 1900s, David Walker, an eminent Australian historian, described Australia as an “anxious nation”. The violence of the 1860s on Australia’s gold fields saw Chinese workers attacked and harassed by Anglo-Europeans. The Chinese were derided as diseased and framed as an economic threat. White Australia was part and parcel of Australia’s birth as an independent nation: laws promoting a white Australia were promulgated as Australia’s federation was formed in 1901. This was Australia’s racial-cultural birthmark, and that’s before we delve into the white settler’s approach to the indigenous peoples of the Australian continent.

White Australia continued officially until the early 1970s though it is arguable that it has never ever receded far, as I have previously discussed.

Throughout its colonial and post-colonial experience, Australia has found comfort and security under the umbrella of a great transatlantic protector. This was a straightforward decision - originally as an extension of British colonialism and then subsequently as a reality of post WW2 circumstances. American military preponderance was sufficient to provide succour to Australia’s defence policy and associated institutional elite establishment for many decades.

If Walker’s “anxious nation” is one bookend of Australia’s relationship with the world, what Allan Gyngell called the “fear of abandonment” is the other bookend. In his book of that title, Gyngell traces Australian foreign policy from 1942. He charts a foreign policy posture that evinced a fear of being forgotten by the great powers. Australian foreign policy, according to Gyngell, sought to protect a large and remote continent with a sparse population. The sense of remoteness was, of course, only meaningful when the foreign policy establishment framed proximity in terms of the transatlantic protectors. That Australia was proximate to other peoples, those of Asia, reinforced the anxieties described by Walker and amplified by the fears generated by distance from the powerful and familiar.

Framed by the agency envelope of anxiety and fear, Asia was the source of the Australian establishment’s uncertainty and insecurity. Australia by necessity sought security from Asia and has, more or less, done so throughout the entire 20th century and now into the 21st century with a number of notable episodes that sought to reframe Australia’s security in ways that recognised the immutability of geography and the emerging realities of Asian economic growth. Ironically, it now appears that as Asia grew economically, and Australian economic engagement with Asia expanded, Australia’s relationship to Asia began to experience a deepening unease.

Asian economic growth, and particularly that of China’s, has laid the groundwork for the disruption of the cosy global order in which American military and economic preponderance could shelter Australia in the event of security tremors. The stronger Asia became; the stronger China became; the more unease would emerge for the U.S. and Australian elite establishment. Australia’s economic integration with Asia, and its growing dependence on this for prosperity, coincided with the progressive diminution of American preponderance in the region.

American preponderance no longer

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the emergence of what can be called the 30 years of American unipolarity, few observers questioned the military dominance of the United States. Between 1991 and 2019, the U.S. expanded its global military interventions under various guises. In this period, it initiated on average 3.7 military interventions per year. This compares with the annual average of 2.4 interventions between 1946 and 1990. American security doctrine saw all parts of the world as America’s dominion. America’s security was a question of global security. This US has over 800 military bases across the globe and pursued kinetic interventions wherever and whenever it saw fit. Its military and defence budget was designed to enable the United States to fight two wars at any one time.

America’s regional and global military preponderance is now in disarray. Its productive and supply chain capacity limitations are now exposed on the steppes of Ukraine and the ever-expanding demands of the unfolding conflict in West Asia. President Joe Biden once responded to doubts about America’s capacity to ‘fight three wars’ asserting that, “for God’s sake, we are the United States of America, the greatest nation in all of human history”. That’s hubris speaking.

The reality is a military industrial complex that has insufficient repair and replace capabilities when measured against the realities of peer conflict.

A recent Reuters investigation found that the collective west’s capacity to manufacture 155mm calibre artillery shells has been seriously depleted through years of miscalculation and neglect. Stockpiles have been depleted in the face of the war of attrition in Ukraine. Production defects are rife in existing manufacturing systems, contributing to an inability to ramp up production to meet the demands of a peer-conflict. Even as efforts are made to increase production, capacity expansions across NATO (including the U.S.) cannot match the output volumes and growth we see in Russia. According to a CNN investigation, in terms of artillery munitions Russia is out producing NATO by a factor of three.

In February 2024, the Pentagon received a report from consultants Govini that evaluated America’s defence contractor supply chain risks. The Govini report Numbers Matter: Defense Acquisition, U.S. Production Capacity, and Deterring China, concluded that:

“U.S. domestic production capacity is a shrivelled shadow of its former self. Crucial categories of industry for U.S. national defence are no longer built in any of the 50 states. With just 25 well-constructed attacks, using any of a variety of means, an adversarial military planner could cripple much of America’s manufacturing apparatus for producing advanced weapons. Under the current U.S. government approach, industry cannot meet production demands to support allies under fire and deter war in the Pacific.”

America’s defence industrial supply chains are highly dependent on international supplies. The extent to which the sector is reliant on non-American supply chains is hard to fully catalogue, given the complexity of the supply networks involved, but Govini notes - as a case in point - that the U.S. defence sector imports various components and materials from over 10,000 Chinese enterprises

.The U.S. Congressional Commission on National Defence Strategy report, issued in late July 2024, concluded that the United States is no longer militarily capable of prosecuting its global ambitions. The report observed, for example, that, “Unclassified public wargames suggest that, in a conflict with China, the United States would largely exhaust its munitions inventories in as few as three to four weeks, with some important munitions (e.g., anti-ship missiles) lasting only a few days. Once expended, replacing these munitions would take years”. More generally, the report concluded that America’s defence industrial capacity is inadequate to its strategic ambitions, confirming the assessments that have emerged over the past few years that unfolding battleground failure in Ukraine began to raise serious doubts about western military capabilities.

The Commission also recognised the inability of the United States to address its military production requirements on its own. Instead, mobilising its various networks of allies globally was identified as necessary if the United States was to match capacity with ambition into the future. In this context, the growing array of minilaterals in the Asia Pacific is evidence of this strategic turn. American capacity limitations are being augmented by the resources of allies such as Japan, Korea and Australia.

In terms of the enlistment of Australia, the AUKUS arrangements are the most noteworthy. The proposed acquisition of American nuclear powered (and nuclear weapon capable) submarines is synonymous with AUKUS. The shift away from conventional submarines, originally contracted from France, to US nuclear submarines has sparked intense public debate in Australia, and to some extent has also amplified American concerns about its own resourcing requirements and limited capabilities. In the U.S. members of Congress have raised doubts about the capacity, let alone the wisdom, of providing nuclear submarines to Australia. The concern is simply that the American submarine sector is presently incapable of meeting America’s own requirements let alone being able to deliver for anyone else. An August 5 2024 Congressional Research Service report identified that current submarine output capacity is between 1.2-1.4 per year, compared to U.S. annual procurement of 2 vessels annually. This situation has resulted in a “growing backlog of boats procured but not yet built”.

These American Congressional assessments have underscored the doubts that some Australian critics have expressed about the practicalities of the AUKUS submarines deal. In response to these doubts, Australian Submarine Agency (ASA) boss Vice Admiral Jonathan Mead recently pleaded for patience but acknowledged that the program will be slow, is likely to experience setbacks and is expensive. These admissions did little to assuage concerns.

Delivery doubts aside, critics have also pointed to the strategic sense of the nuclear submarines. Defence analyst Sam Roggeveen - in his book The Echidna Strategy - has argued that the AUKUS pathway exposes Australia to considerable strategic risks, particularly those associated with America’s “staying power” in Asia. He argues that Australia would be better served with a strategy that focused closer to shores. Roggeveen concludes:

“It (AUKUS) is a project of vaulting ambition that is out of step with Australian tradition as a middle military power, wildly at odds with our international status and, most importantly, a wasteful expenditure of public money that will make Australia less safe.”

These critiques of AUKUS and the nuclear submarines component of the deal have also been aired by others, such as Hugh White. As recently as 3 August 2024 he warned New Zealand away from joining AUKUS. AUKUS is arguably meaningful only in the context of a ‘forward defence’ in which a presence in and around China is warranted. This may make sense for an American strategy that seeks to contain China but it makes no meaningful sense from the point of view of defending Australia itself. Indeed, the question of sovereignty has been raised by critics of AUKUS, concerned that the agreement amplifies Australian subordination to the U.S. in the determination of its foreign and defence policy priorities.

James Caverley, a researcher at the US Naval War College, raised concerns that procurement decisions were driving grand strategy, rather than the other way around, and that “Australia, and any other country entering AUKUS in the future, will pay in autonomy as much as in dollars”. Other scholars, such as Lloyd Cox and his co-authors, have argued that “AUKUS is the latest expression of Australia’s strategic culture which is premised on a fear of abandonment and a conviction that Australia’s core security interests can only be guaranteed by the support of the U.S.”

Declining relative military power is stoking anxieties in Washington and Canberra. Canberra’s hope is to reinforce subimperial fealty so as to mitigate the risk of abandonment. The problem is, the strategic rationale is dubious and, in any case, undermined by operational problems.

A changed world demands adaption

AUSMIN convened for the 31st consecutive time in the US a couple of weeks ago, against this backdrop. Australia’s subimperial reflex continues to draw it inexorably towards a commitment to a world order that no longer exists, but one that the U.S. seeks to reclaim in some form or another. This is evident in the joint statement. American strategic imperatives in Asia define the principal objectives and underlying rationale of the AUKUS arrangements specifically, and of the wider US-Australia alliance more generally. This has become clearer as details of the updated arrangements emerged. While Australia is committed to continue funding for the nuclear submarines, there are no guarantees that either the U.S. or UK must deliver on them. Indeed, both transatlantic powers can pull out of the deal but still require Australia to host American nuclear-powered, and potentially nuclear weapon

Yet, these moves are inconsistent with the aspirations of countries of Asia, and southeast Asia in particular, for whom ASEAN centrality is the cornerstone of regional peace and prosperity.

The AUSMIN joint statement speaks of a shared commitment to ASEAN centrality, but the US-Australia alliance structure, the growing array of minilaterals and the military expansions being pursued by the US and its sundry allies all serve to sidestep or reduce the pivot role that ASEAN can and should play in the region’s affairs. This is an irreconcilable contradiction in Australian foreign policy.

The world has changed from the times and conditions when Australia could simply rely upon its subimperial reflex. The U.S. is no longer the unquestioned military power regionally, let alone globally. The U.S. economy is no longer the dominant force it once was. Australia’s defence strategy, however, is increasingly locked into the imperatives of those of the United States, as the U.S. seeks to reclaim Asian primacy. In these circumstances, the risks to Australian prosperity and security are significant and laid bare.

Economic growth has swung decisively in the direction of the economies of the global majority. Long suppressed and exploited by colonial domination, the countries of the ‘global south’ are gathering momentum. Much of this momentum is in Asia, and southeast Asia in particular. A large part of this emanates from deepening economic integration with China, whether it be by way of trade or the development of infrastructure.

The contradictions at the heart of Australia's foreign and defence policies grow starker as the world continues to change. China’s rise has catalysed a protracted and evolving bout of displacement anxiety in the U.S. and by extension, amongst the security establishment in Australia. China’s rise has exposed the gaping contradiction in Australia's foreign policy posture. Australia remains wedded to the American-dominated world order even as this order continues to weaken.

By doubling down in an approach that seeks ‘security from Asia’, the risk to Australia is a refusal to find security in Asia at a time when this is what’s needed the most.