Profit Realisation, Productivity and the Siphoning of System Liquidity

Theoretical Reflections in the Context of the Systemic Exchange Value / Thermoeconomics Framework

Prefatory note: this essay continues explorations of conceptual or theoretical themes within the broader Systemic Exchange Value (SEV) or thermoeconomics framework I have been developing. The foundational essay in the SEV framework can be found here. This framework seeks to develop an integrated theory of material production systems through thermodynamic lenses, financial flows and information systems. In this essay, I discuss questions of profits and their relationship to system credit or liquidity expansion on the one hand, and the material constraints of productive systems and industry structure on the other. Related essays interpret Chinese industrial profits data through structural lenses including this one that addressed the August 2025 data and this one that considers the October data release.

In monetary production economies governed by endogenous money, profit cannot be understood simply as the outcome of productive activity or surplus generation. Rather, profit strictly speaking is a monetary phenomenon; it is a realised claim on circulating exchange value that depends fundamentally on new injections of system liquidity. However, once this condition is met, the distribution of profitability across sectors and firms is shaped by a combination of physical productivity, positional access to credit and the structural siphoning of liquidity into fictitious capital circuits. Sector structure and market power further condition the ability of dominant firms to convert access to liquidity into durable profit streams. This note outlines a framework in which aggregate profit requires net liquidity injection, while profit distribution reflects a complex interplay of material, monetary and institutional asymmetries.

Profit as a Claim on System Liquidity

In an economy where money is endogenously created - primarily through commercial bank lending and via government spending - profit emerges not as a residual of production per se, but as a monetised claim on aggregate exchange value in circulation.

In any given period, profit - understood as surplus exchange value - is only realisable if sufficient money capital is in active circulation to cover the costs of production and to validate surplus claims. Since not all system liquidity is in motion at any point in time - some money capital remains dormant, tied up in reserves, idle balances or ‘strategic’ hoards - the realisation of profit requires new net liquidity to enter circulation. This often takes the form of new system liquidity expansion, either through bank lending to firms and households or through public sector net spending.

Thus, in aggregate terms, profit is only possible if new liquidity is injected into the system in excess of the amount necessary to sustain current production. This liquidity must compensate not only for the leakages and hoarding of money capital but also for the structural asymmetries in access to money capital that typify capitalist economies.

Consequently, for profits to be realised system-wide, new liquidity must be injected in a net fashion, that is, beyond the volume needed to reproduce current production accounting for liquidity drainage via loan repayments and taxes. These injections are typically channelled via commercial bank credit to the private sector or through fiscal expenditures by the state. Without such injections, firms cannot collectively realise the potential of monetised profits through the circuits of production and circulation, regardless of technical efficiency or productivity growth.

In this respect, system profit is not a function of surplus production per se, but of monetary validation. This perspective emphasises the need for credit-mediated circulation to complete the M–C–M' circuit. We can put it another way: profits emerge as over-claims on a growing pool of exchange value (liquidity), enabled only through continual net injections of money capital. (Note that for the purposes of this discussion the distributional institutions between labour and capital are not addressed.)

The Role of Dormant Capital and Credit Dependency

Given the continual presence of dormant capital - held as financial assets, idle deposits or hoarded cash - there is an inherent liquidity shortfall within the productive circuit at a given level of output. This gap means that even if previously created money exists in the system, it may not be available for immediate use in commodity exchange and profit realisation. That is, it is not in circulation.

Hence, capital accumulation and profit realisation require net injections of liquidity or system credit, sufficient to mobilise productive activity, facilitate wage and input payments and support demand that allows for the realisation of monetary profit. This mechanism also highlights the fragility of accumulation dynamics. When credit slows or liquidity injections decline in net terms, profits falter, not because productive capacity has diminished, but because the monetary preconditions for realisation have evaporated.

Since all capital accumulation implies the reinvestment of (at least some) profits (i.e., exchange value enables new production, which drives surplus and creates the new exchange value), and because production of use-values alone does not guarantee their conversion into realised profits (exchange value), the system needs a means to ‘over-compensate’ for leakages and dormant capital. So we can say:

Systemic profit is only possible when liquidity creation exceeds the stagnation implied by dormant money capital.

Put differently, the reproduction of circuits of production (M–C–M') is predicated on expanding the pool of liquidity available for profit realisation, but this expansion cannot simply mirror existing money capital; rather, it must exceed it, or the circuit breaks down in underconsumption or overproduction crises.

In schematic terms, we can thus describe the process as follows:

Initial State: Existing money capital (M₀) partly dormant, partly circulating.

Credit Injection (ΔM₁): New commercial/government credit increases circulating liquidity.

Production (C → C'): Use values produced, anticipating realisation via sale.

Exchange (C' → M'): Realisation of surplus depends on sufficient M being in circulation.

Profit (M' – M): Realised only if ΔM₁ > ΔD (where ΔD = change in dormant capital).

Reinvestment or Hoarding: Realised profits either re-enter circulation or become new dormant capital.

Cycle Repeats: Each round depends on continued injection of net new credit to keep the system solvent and growing.

Productivity and the Distribution of Profitability

Once the system-level condition for profit is met (i.e. sufficient liquidity injection), the distribution of profit across sectors depends partly on material productivity differentials. Firms or sectors that can generate more output per unit of input are, in principle, better positioned to capture a larger share of available monetary surplus provided that output can be sold and monetised.

This reinforces the classical view that productivity underpins competitiveness. However, in the Systemic Exchange Value framework that I have been developing, productivity is a conditioning variable, not a sufficient one. That is, a firm can be highly productive in physical terms but still fail to realise high profits if it cannot secure access to circulating money capital; or, if it faces tight margins due to intense competition and weak bargaining power.

In this way, productivity determines the potential surplus, but actual profit depends on access to money capital and positional strength in the circuit of monetary flows.

Fictitious Capital and the Siphoning of Liquidity

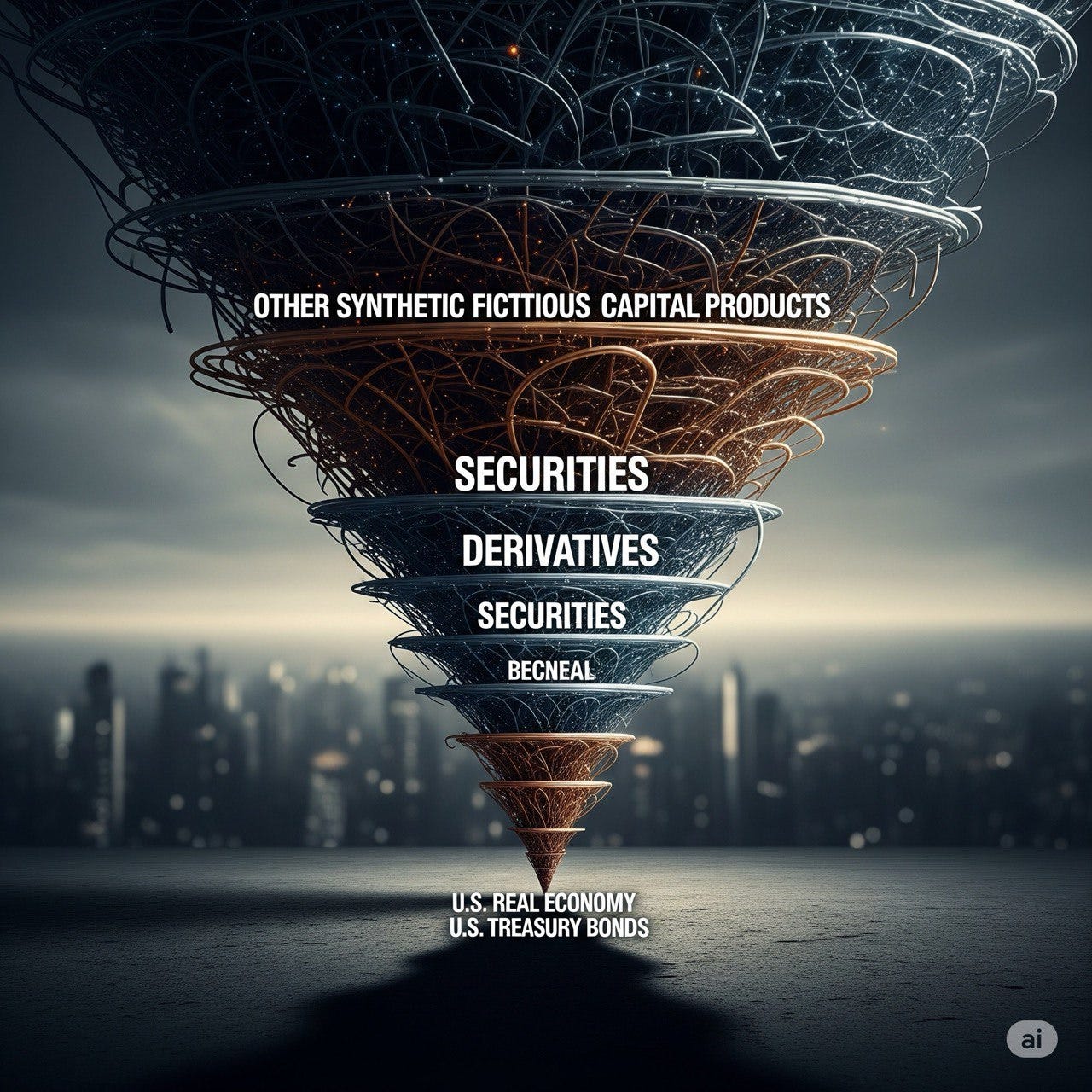

In financialised economies, a growing share of system liquidity is not deployed in the reproduction of use values, but is absorbed by fictitious capital circuits. These circuits are composed of financial assets (e.g. stocks, bonds, real estate, derivatives etc.) that represent claims on future use value but do not correspond directly to the current production of goods and services.

When liquidity is diverted into fictitious circuits, the stock of money capital in the real economy diminishes and circulation velocity of money in the real economy slows. In these conditions, productive sectors may face relative illiquidity, regardless of their technical efficiency. Asset price inflation may generate paper profits for financial actors and holders of fictitious capital, but it does not resolve the need for circulating money capital in sectors engaged in the production of goods and services (that is, those involved in the harnessing and transformation of energy and materials).

As a result, the monetary (or liquidity availability) conditions necessary for profit realisation in the productive economy deteriorate, even as apparent wealth increases in asset markets. This creates a structural fragility: profit expectations are sustained by ever-larger injections of liquidity, but the bulk of this liquidity is absorbed by financial markets rather than circulated through production and consumption. Fictitious capital asset values in money terms rise at the expense of capacity elsewhere in the economic system.

Sector Structure and Market Power

A further determinant of profit distribution is sectoral structure, specifically, the degree of market concentration and the extent to which firms possess pricing power or command over financial flows. In oligopolistic or monopolistic sectors, or at least those in which some firms are dominant, the dominant firms are structurally privileged in several ways. They can set prices above costs (markup pricing). They have direct access to credit markets and preferential lending terms. Due to their size, they can influence government policy, subsidies or regulatory regimes creating rent garnering opportunities, and they possess the political and legal infrastructure to entrench their rent-extraction mechanisms.

In such structures, firms can impose themselves upstream in the distributional hierarchy, capturing a disproportionate share of available system liquidity, regardless of their relative productivity. Profit becomes not just a reward for productivity, but a function of power: the ability to convert liquidity into durable claims on exchange value.

This is particularly evident in digital platform monopolies, pharmaceutical conglomerates and energy giants; that is, firms that, while not always the most physically productive, can nonetheless command vast flows of money capital due to entrenched market positions, intellectual property monopolies or control of strategic infrastructures. In such environments, profit becomes a function of power as much as productivity. These firms are well-positioned to impose their liquidity claims upstream. That is, they can extract shares of system profits-in-potentia not just from production, but from control over circulation, branding, data, intellectual property or network effects.

By contrast, in competitive sectors profitability is structurally constrained. Even with high physical productivity or social utility, these sectors are often last in the financial hierarchy (though not always), squeezed on both cost and price, and vulnerable to credit cycles and liquidity tightening.

Thus, the distribution of profit reflects both material and institutional asymmetries: the capacity to generate use value, and the power to convert that use value into monetised exchange value within a system governed by unequal access to liquidity.

The core logic, therefore, involves the following three propositions:

Liquidity is a system constraint on profit realisation;

Productivity and market power shape the relative distribution of profit; and

Fictitious capital siphoning suppresses real profit flows.

We can see these dynamics play out in the US. As Aidan Regan has pointed out recently, across all US firms, “nearly 99% of after-tax profits are captured by the top 10%, with the top 1% alone accounting for more than 93%.” He goes on to observe that, “the top 0.1% of firms – just one in a thousand – have a gravitational pull over profit flows that dwarfs the rest of corporate America.” The dynamic is most pronounced in IP-intensive sectors of the so-called knowledge economy where the top 1% of firms in the big technology and pharmaceutical sectors claim almost all sector profits. These firms are publicly listed whereby they contribute to the siphoning of liquidity away from real profit flows.

Summation

This theoretical note proposes a structural, monetary framework for understanding how profit is generated and distributed in financialised economies. In contrast to neoclassical or purely real-side accounts, it emphasises the systemic dependence of profit on liquidity creation, the asymmetries introduced by fictitious capital, and the institutional power structures that shape credit allocation and market outcomes.

In this framework:

Profit realisation is a monetary condition, tied to the continual expansion of credit and the mobilisation of money capital;

Profit distribution is conditioned by physical productivity (production coefficient and the labour-capital mix, which are determined separately), sectoral structure and financial positioning; and

Fictitious capital absorbs surplus liquidity, distorting the profitability of productive use value sectors and necessitating larger and riskier credit injections into the systems of circulation writ large.

A number of critical observations follow from this overall theoretical approach. As noted, overall profitability is not a function of physical productivity, but of system-level liquidity dynamics and access to new money capital mediated through specific industry structural set-ups. Credit growth rate is critical to system stability or crisis. Crisis emerges when credit growth slows, not because of physical constraints per se but because profit claims cannot be realised. Endogeneity of money means the system is always in tension between growth (requiring net liquidity injection) and collapse (if dormancy overwhelms injection). Lastly, fictitious capital (asset prices) may rise even in the absence of real profitability. This happens if new liquidity is routed into fictitious capital asset markets rather than circulation in use value productive circuits.

In this framework, I distinguish clearly between the conditions for the realisation of profit (which are monetary and systemic) and the distribution of profitability (which is conditioned by material productivity, supply chain power and financial hierarchy). This provides a useful lens for understanding modern capital accumulation dynamics, where aggregate profits depend increasingly on financial liquidity expansion, yet the productive base of the economy may be hollowed out by the expansion of fictitious capital circuits.