The contrasts couldn’t be clearer.

On 27 June 2024, the world was witness to what, under normal circumstances, might be called a US Presidential Debate. A day later, in Beijing, China hosted a Conference marking the 70th Anniversary of the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence.

While Presidents Joe Biden and Donald Trump traded insults, vented jeremiads about each other’s legacies, performance and competencies and ventilated a farrago of falsehoods, China’s Xi Jinping implored those in attendance in Beijing to promote the Five Principles to safeguard international fairness and justice and uphold true multilateralism.

The Chinese hosts issued a summary of proceedings, which included among other things, a call for nations to “jointly defend the international system with the United Nations at the centre and advance global governance characterised by extensive consultation and joint contribution for shared benefit.” As China’s President heads to Astana, Kazakhstan to join other leaders at the 24th Meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Council of Heads of States (3-4 July 2024), the ethos of mutual coexistence will resonate, as participants continue to work towards “true multilateralism” and realise security and prosperity.

A few days later, on 7-9 July, NATO members will converge on Washington ostensibly to celebrate the military alliance’s 75th anniversary, but with an eye to expanding its operational purview beyond the North Atlantic. As if to preempt NATO’s globalisation, its outgoing director-general, Jens Stoltenberg, recently claimed in an interview with a Japanese media outlet, China was responsible for the Ukraine war in Europe; in doing so, he was laying the rhetorical groundwork to rationalise NATO’s expansion into Asia. That he ventilated this line to a Japanese audience is not happenstance, either. NATO’s expansion into Asia comes as no surprise, of course, given its previous (stymied) attempts to establish a presence in Japan, not to mention the intensification of European naval presence in the Asia Pacific.

This concentrated flurry of activity and events has brought the state of global affairs into sharp relief:

A commitment to multipolarity or an attempt to reimpose unipolarity

A refusal to form blocs and respect for neutrality or a manichean world view the promotes and rationalises “kinetic” intervention

A pursuit of positive peace through integrated development or a precarious insecurity founded on failed deterrence doctrine

Turn to Eurasia and the Asia Pacific

The recent cluster bombing of civilians in Crimea on 23 June 2024, and Russia’s response to it, can be seen as another significant milestone and the geographic transformation of global security. Since 2014, Russia has progressively turned towards its east in search of economic development and security. While Russia had not abandoned hopes of achieving a new security architecture with western Europe, even as late as December 2021, the unfolding events of the conflict in Ukraine - and the progressive escalation enabled by the provision of financial and military aid to Ukraine by NATO and the collective west broadly speaking - have brought the curtain down in centuries of effort to more effectively align Russia with its western european neighbours.

Two moments in response to the cluster bombing of Crimea mark the consolidation of this eastward turn, but with broader implications. Firstly, Russia made clear that it held the US responsible for the attacks. The American Ambassador in Moscow was summoned and provided with a demarche on 24 June 2024, warning the Americans that retaliation was inevitable. The Russians noted that the relations between Russia and the US was no long one of being “at peace”.

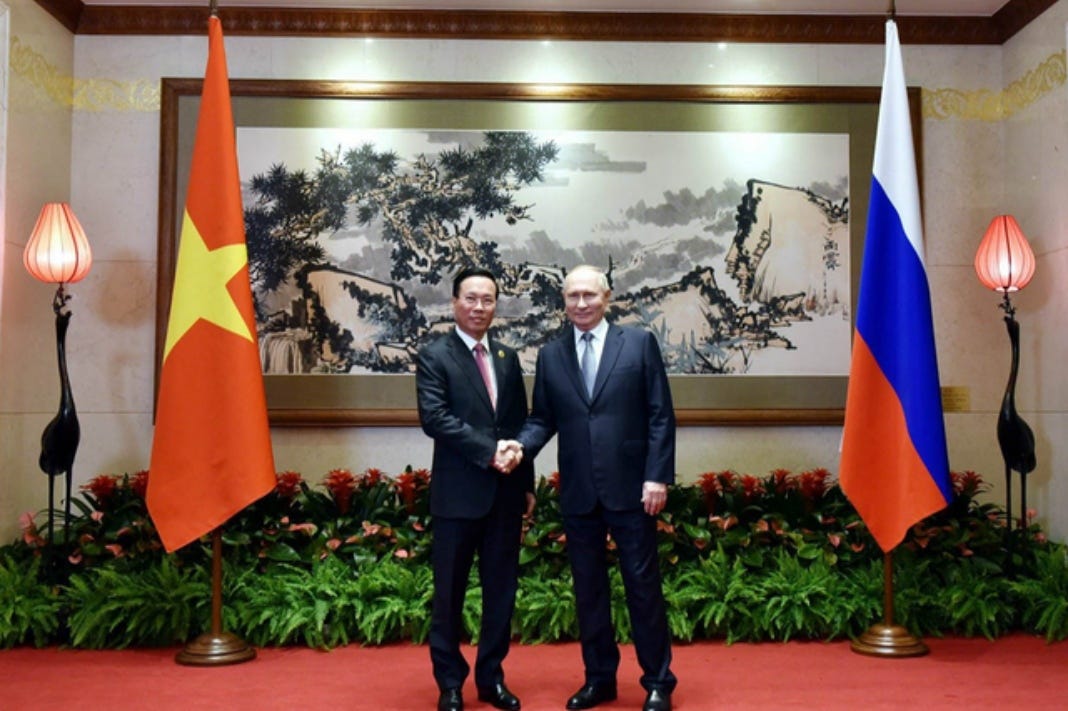

But there is more to the situation than how Russia responded immediately to American involvement in the Crimea attacks. The significance can be fully grasped when placed in the context of Russia President Vladimir Putin’s call, on a visit to Vietnam a few days previous (June 20, 2024), for a new security architecture for the Asia Pacific region, and for a concomitant call for a new security architecture for the Eurasian continent. Putin observed:

“The discussion of the situation in the Asia-Pacific region showed mutual interest in building a reliable and adequate regional security architecture based on the principles of the non-use of force and a peaceful settlement of disputes, in which there will be no place for selective military-political blocs”.

Three points stand out.

First is the geographic scope: the Asia Pacific. Putin’s visit to Vietnam came off the back of a visit to the DPRK (North Korea), during which the two nations signed a new security agreement. This visit was a stark reminder that Russia is also a Pacific power. Russia’s Pacific fleet is being upgraded, and its newest nuclear submarine will operate from its base on the Kamchatka Peninsula. The fleet just held exercises in the waters of the Pacific Ocean (18-26 June 2024), the Sea of Japan and the Sea of Okhotsk involving some 40 vessels.

Putin elaborated on his remarks in Vietnam, observing that:

"Our countries firmly safeguard the principles of the supremacy of international law, sovereignty and non-interference in the internal affairs of other states, efforts at key international venues, including the UN and as part of the Russia-ASEAN dialogue”.

Again, observe the geographic frame of reference, including the dialogue format between Russia and ASEAN. The security architecture proposition being advanced by Putin thus has a sweeping geographic reach, including the Eurasian continent and extending into the Asia Pacific region.

The second point to note is the emphasis on peaceful resolution of disputes. There is a clear view that a viable security architecture must be premised on functional dialogue as the principal means of dispute resolution. The third point to note is the objection to “selective military-political blocs”.

Such a security architecture is, therefore, not one designed on the basis of military-based deterrence as its guiding design philosophy but one of building institutions that align interests to create ‘nested’ mutual interests; that is, “equal and indivisible security”.

SCO and Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence

This brings us to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and the 5 Principles of Peaceful Coexistence.

The SCO comprises 9 member states and is expected to expand to 10, when Belarus is admitted. Mongolia remains an observer. In addition, there are currently 14 SCO ‘dialogue partners’ that may also be future candidates for full membership. This group includes a large proportion of Arab states, including Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, plus others across the Eurasian landmass such as Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Turkey.

Since its establishment in 2001, the SCO has focused attention on addressing questions of security in a number of ways. First, questions of security are largely oriented towards endogenous issues, addressed to concerns around religious extremism, terrorism and separatism. Put another way, the orientation of the SCO isn’t so much about developing a military posture addressing exogenous risks, but about addressing the conditions of social stability and instability. The role of exogenous factors in catalysing and exacerbating destabilisation via terrorism, extremism or separatism was, however, recognised when Chinese President Xi Jinping in September 2022 explicitly warned of the need for SCO member states to be increasingly vigilant in regards to externally instigated destabilisation actions and ‘colour revolutions’. He reiterated this warning in July 2023.

Second, the SCO has approached security in ways that recognised economic development was, and remains, a key to regional security. Indivisible security can, as such, be understood not only through the prism of collaboration between states on anti-colour revolution initiatives, but through the facilitation of economic development. Here, we can see ambitions that go beyond the narrow notion of a ‘negative peace’ - defined as merely the absence of military conflict and violence - to one of ‘positive peace’. This distinction was originally introduced by Johan Galtung in 1964, articulating a more expansive concept of peace to involve the absence of ‘structural violence’ and the presence of harmony. Aspects of structural violence in trans-national relations include the presence of gross economic inequities both between nations and within nations. As such, overcoming the challenges of un-development and uneven development is a key plank in any program aimed at instituting and sustaining ‘positive peace’.

The five principles of peaceful coexistence, agreed some 70 years ago by a multitude of nations - most of which are members of what today is called the ‘global south’- also articulated an ethos with actionable behavioural parameters that could, arguably, contribute to a ‘positive peace’ agenda. The five principles are: (1) mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, (2) mutual non-aggression, (3) non-interference in each other's internal affairs, (4) equality and mutual benefit, and (5) peaceful coexistence.

First articulated by Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in December 1953 when he met an Indian Government Delegation, the principles were agreed between the Prime Ministers of China and India in a Joint Statement issued on June 28, 1954 and affirmed in a bilateral statement between the Premiers of China and Burma (now Myanmar) on June 29, 1954. In 1955, the Asian-African Conference, convened in Bandung, Indonesia, adopted the ten principles for conducting international relations, which included the original Five Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence. The Five Principles were subsequently incorporated in the Declaration of Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, by a resolution of the UN General Assembly in 1970.

Principles translated into practice is no easy feat, and misalignments are an unfortunate reality. This doesn’t invalidate the principles, however. Rather, these misalignments demonstrate the need to continue to work to improve the conditions in which such principles can be readily implemented and sustained.

The SCO is in some respects an embodiment of these principles in action. Since its inception, the SCO has managed to achieve a number of important outcomes when it comes to regional stability and security for member states. Firstly, within the framework of the SCO, all disputes concerning over 3,000km of borders between China and the former Soviet Union were resolved. With the joint efforts of China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the disputes were resolved in six years.

Secondly, cross-border terrorism has been successfully curtailed. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union (1991) and the emergence of the Taliban in Afghanistan, there was considerable concern about the destabilisation effects of extremism and terrorism afflicting Central Asia. On June 15, 2001, three months prior to the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, leaders of the six founding states of the SCO signed the Shanghai Convention on Combating Terrorism, Separatism and Extremism. This Convention was the first international treaty on anti-terrorism this century. It established the legal framework within which SCO states would counter terrorism and coordinate in joint counter-terrorism efforts. Within the framework, SCO member states cooperated and established the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) to combat and contain extremism and terrorism in the region.

Third, containment. The SCO has successfully contained conflicts and mitigated contagion risk. The ethnic and religious conflicts and issues present in Central Asia require deft handling. The SCO mechanism provided a workable set of mechanisms by which members could coordinate efforts to dampen the risks of instability and limit the risk of regional conflicts from spreading. The management of the conflict in Afghanistan is one of the SCO’s success stories. With the situation in Afghanistan stabilised, it is now possible for interested parties to explore the necessary efforts to shift towards a pathway for the construction of a positive peace. Economic development is a key element of this pathway.

The end of deterrence?

Johan Galtung observed that one will never reach peace through security, but one will reach security through peace.

This observation encapsulates the contrast in ethos between NATO on the one hand, and the SCO on the other. It also points to a key difference between the emerging possibilities for global governance. Just as the SCO is considering its own expansion through the inclusion of Belarus, so too is NATO contemplating its own expansion into the Asia Pacific.

Whereas NATO privileges a narrow conception of negative peace through militarised security, the SCO - drawing on the richness of the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence - explores a more constructivist approach to global ordering. NATO’s birth was defined by an external Other; the Soviet Union. Despite the dissolution of the Soviet Union, rather than disbanding itself, NATO sought to extend its existence through the confection of enemies. Enemies are a precondition for a security state defined by a deterrence posture; without an enemy or enemies, the idea of deterrence begins to crumble. Despite commitments not to, after the dissolution of the USSR, NATO pressed to expand eastwards. NATO’s enemy was and remains in the East; Russia, and progressively, China.

Outgoing NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has recently accused China of inciting the “largest military conflict in Europe since World War 2”. He argued that a “cost” should be placed on China for its provision of dual use technologies to Russia. The sanctimony and double standards in this claim are self-evident, but it is the rhetorical effects that are worth noting. In effect, what Stoltenberg is seeking to do is reframe NATO’s enemies to rationalise its globalisation. NATO is no longer there to ward off Russia; it is up against China too. NATO has long been deepening its alignment with what it calls its “partners in the Indo-Pacific region”. It now appears that as NATO prepares to meet in Washington on July 9, 2024, it is readying the world for a NATO push into Asia itself.

The NATO raison d’etre has been framed by the deterrence discourse that has demonstrably failed in mitigating conflict. The latest failures are found in Ukraine itself, where the near-decade build-up of the Ukrainian army failed to deter Russian intervention in early 2024. Russia’s long standing concerns about NATO expansion, articulated by Putin as early as 2007, were not to be assuaged by the NATO-isation of the Ukraine military. The risks were well known in 2014, but ignored - or worse still, actively exacerbated by the actions of NATO and the collective west generally as the Minsk Agreements were willfully ignored. Ukrainian bombing of the Donbass increased in late 2021 and into early 2022. Rather, it was due precisely to this military build-up in Ukraine and intensified bombings that catalysed Russia’s self-declared special military operation.

Despite the massive asymmetry between the Israeli armed forces and those of Hamas, the theoretical deterrence effects failed dramatically on October 7, 2023 as Lawrence Freeman has demonstrated. The failure of deterrence in West Asia has also been on display with the impotence of the American-assembled and led Prosperity Guardian naval mission to stymie the Houthi attacks on shipping through the Red Sea. When the US marshalled the naval intervention to deter the Houthis, the collective west not only underestimated the Houthis’ capacities but overestimated the effects of force projection. Deterrence as a doctrine simply has not delivered.

Achieving peace is a lot more than the pursuit of security through deterrence. There are real doubts as to whether in fact such an approach can meaningfully work in an environment in which there is clearly no longer a clear asymmetry of power. And even then, as the situation in West Asia suggests, power asymmetries aren’t sufficient to ward off violent attacks. Achieving security requires the realisation of a positive peace; this requires a reappraisal of the institutions necessary for peaceful co-existence. It also presupposes a multipolar ethos that accepts the presence of difference and foreswears the security claims of one over the security imperatives of others.

Contrasting possibilities

As NATO gathers in Washington to consider the expansion of its failed doctrine of deterrence-based negative peace, the world has alternative possibilities. The Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence lays down important markers, and institutionally, the SCO is suggestive of an approach that integrates economic development as an intrinsic component of positive peace. The SCO has nine members; soon to become ten. It has 14 observers, stretching from South East Asia through West Asia and to West Europe. And so we are prompted to wonder:

Is the bloc-free neutrality ethos of the SCO more aligned with the ethos of Asian multipolarity as embodied in ASEAN?

Do the nations and peoples of Asia want NATO-style insecurity in the region, brought about by heightened militarisation in the name of deterrence, or do they see the possibilities of enjoining a wider, holistic security through peace architecture, such as SCO, that aligns the domestic economic and social stability interest of nation states with the wider security interests of others?

A positive peaces requires dialogue, patience and respect of others. It isn’t achieved at the end of a gun barrel. It depends on a capacity to negotiate consensus, rather than impose solutions by dint of external force. A positive peace isn’t a utopian panacea, but a constructive alternative to the failed approaches dominated by the collective west and NATO.

Is it time to find a pathway to a multipolar peace?