Prefatory comments: This is part of a series of essays that builds from a foundational ongoing work in conceptual bricolage that seeks to develop an integrated account of our socio-economic systems through the lens of thermodynamics, information and money. The framework or approach has been dubbed Systematic Exchange Value (SEV), and seeks to place thermodynamics at the centre of how we understand system dynamics. The foundational (long) piece is here. In this essay, I explore China’s renewable energy turn through the lens of energy surplus generation and discuss this in both systemic development terms (as a contrast to entropy tendencies) and as a geopolitical move that has important sovereignty and security implications. Contrasting the situation with that in the US and the Middle East sheds light on the strategic significances.

In 1992, James Carville, a strategist for Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign, coined the now-famous phrase: “It’s the economy, stupid.” It was a reminder that economic conditions, not abstract ideology, ultimately drive politics, welfare and power. Today, a revision - or refinement - is in order: it’s energy, stupid.

In the 21st century, the question that underpins economic strength and vitality, geopolitical autonomy and systemic welfare is no longer just growth; it is the quality, surplus and sovereignty of energy. Nations that can generate abundant net energy - that is, energy remaining after energy inputs are deducted - are systemically advantaged. Those that cannot are increasingly exposed, not only economically but geopolitically.

The Surplus That Powers Everything

Behind every good, service, data centre or military industrial complex lies energy. But not all energy is created equal. The real measure of an energy source’s viability is its Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROEI): the ratio of energy produced to the energy required to produce it. High-EROEI systems generate vast surpluses that can be reinvested into the economy and the social settlement. Low-EROEI systems drain the economy, requiring ever-greater effort for diminishing returns.

Historically, the world’s fossil fuel system operated with EROEIs of 50:1 or even 100:1 in the early days of Middle Eastern oil extraction. But these days are fading. Much of the oil that remains is harder to reach and more energy-intensive to extract. Shale oil and tar sands, for instance, offer returns as low as 3:1 to 5:1, barely above breakeven when broader system costs are included.

This shift matters because it implies rising entropy. The more of society’s productive effort that must be redirected just to sustain energy flows, the less available there is for everything else - housing, health care, education, recreation or innovation. The economy becomes a snake eating its own tail.

China’s High-EROEI Pivot

Between January and May 2025, China added 198 gigawatts (GW) of solar and 46 GW of wind energy capacity, which together are enough to match the total electricity generation capacity of countries like Indonesia or Turkiye. But what matters more than headline numbers is system composition: the fact that renewables are driving a larger share of China’s total energy growth signals a systemic pivot. The New York Times recently featured an article that compared the energy exports profiles of China and the USA. The summary is illustrated powerfully in the graphic, reproduced below.

China is not merely electrifying, it is electrifying strategically. By investing in renewables, which now offer EROEIs in the range of 10:1 to 30:1 for solar and up to 50:1 for onshore wind, China is increasing its net energy surplus per unit of investment. Put plainly, renewable energy costs are falling and in significant comparative ways. And unlike fossil fuels, these systems are not dependent on volatile foreign supply chains. Once installed, a solar panel or wind turbine requires no fuel imports, no naval protection of shipping lanes, no dependency on unstable regimes or the need for protection against geopolitical instabilities.

This shift is both economically rational and geopolitically shrewd. It enhances systemic welfare by reducing internal energy entropy and promotes sovereignty by insulating China from exogenous shocks in oil and gas markets. In Systemic Exchange Value terms, China is shifting the foundation of its economy away from often speculative, financialised circuits tethered to volatile commodity flows and toward self-reinforcing domestic value circuits powered by clean, surplus-producing infrastructure.

Root and Branch: Why Storage and Materials Matter

China’s energy strategy isn’t just about volume of electricity generation. It is also about system integration. In Systemic Exchange Value terms, it’s about ensuring that the exchange value stability and surplus usability of renewable energy is maximised. This means controlling not just the source, but also the storage, conversion, and application layers of the energy system.

China’s energy transformation is not merely a matter of generation capacity. It is systemic. Recognising that solar and wind are intermittent sources, China is investing heavily in storage, conversion, and load-balancing infrastructure. This is the deeper layer of energy sovereignty: ensuring that surplus energy is usable when and where it is needed, without relying on external technologies or supply chains.

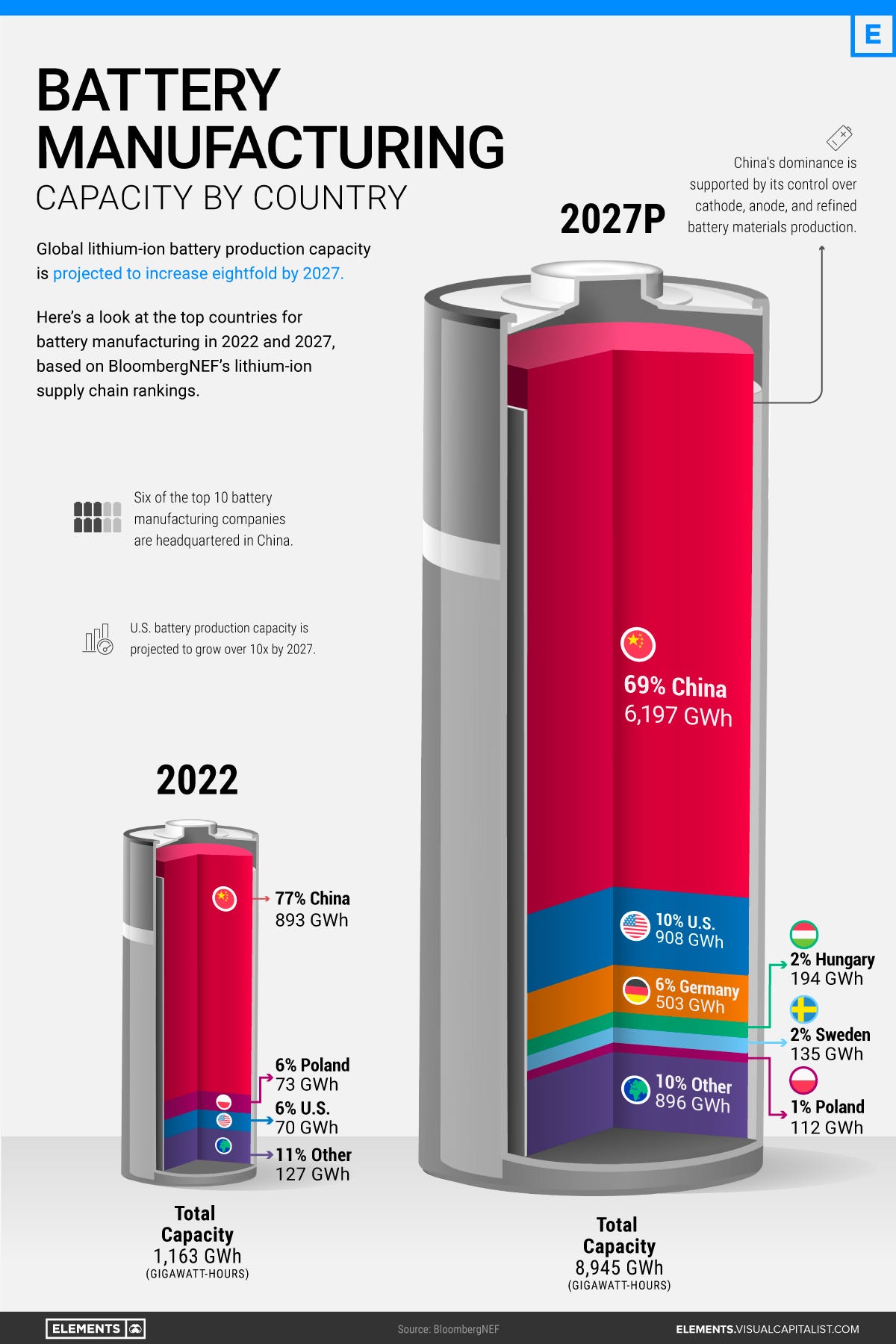

This explains why China’s leadership in battery technology is no accident. The country dominates the entire battery value chain, from lithium processing to cathode materials, electrolytes, and final cell assembly. These aren’t just industrial capabilities, they’re chemically intensive platforms for net energy stabilisation. In effect, battery and material science breakthroughs are what make China’s high-EROEI renewables actually system-compatible. Without them, surplus energy would be stranded; but with them, it becomes mobile, dispatchable and monetisable.

It’s here that China’s root-and-branch approach becomes clear. From solar panel production to grid integration, from rare earth processing to EV manufacturing, China is constructing an end-to-end infrastructure of energetic sovereignty. It’s an ecosystem play. This is not just the replacement of one fuel with another. It is the strategic reengineering of the national energy metabolism; it is a deliberate move to anchor long-term prosperity in physics, not geopolitics.

Beyond Substitution: Energy Transitions as Additions

Much of the mainstream discourse around energy “transition” assumes a linear replacement: that societies move from one dominant energy source to another in a clean swap; from wood to coal, coal to oil, oil to renewables. But as Jean-Baptiste Fressoz convincingly argues in his book More and More and More, this is a historical myth. Human societies have rarely - indeed, if ever - replaced energy sources in the past. Instead, they have stacked them, adding new sources on top of existing ones to meet rising energy demands.

In this light, the real transformation lies not in abandoning fossil fuels, but in reducing their proportionate role in driving economic welfare. That’s what’s happening in China today. Despite continued use of coal and oil, the incremental source of energy for new value creation is increasingly coming from renewables. In other words, China is not replacing fossil fuels outright; it is shifting the marginal source of surplus energy, that is, the energy that powers the next unit of economic output and consumption and the next wave of productive capacity, away from entropy-heavy sources to surplus-efficient ones.

This distinction is crucial. It helps explain why China’s renewable build-out matters even if coal plants still operate: because each new solar farm or wind installation reduces the dependency ratio of traditional energy within the broader system. Over time, this reweights the energy metabolism of the economy in favour of high-EROEI, low-risk, geopolitically sovereign sources, even as older sources persist in the background. As for coal plants, their systemic role is also shifting as a result, as new facilities begin to operate as supplementary capacity generators rather than fulfil the more traditional so-called base load capacity role.

Framed this way, the transition is not a switch, but a directional reprogramming of the national value circuit toward systems that deliver greater welfare per unit of invested energy.

This also reframes what sovereignty looks like. Sovereignty is not achieved simply by “cutting off oil” or “electrifying everything.” Rather, it is achieved when the proportion of energy needed for system maintenance declines, and the proportion contributing to social and productive surplus increases. That’s the surplus that allows a society to breathe, plan and flourish.

Even oil giants know the game is changing

Even countries with abundant, cheap oil are pivoting toward renewables, not because they have to, but because they understand what’s coming.

The best confirmation that a new energy logic is emerging comes not from climate activists, but from oil-rich nations themselves. Across the Middle East, especially in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar, massive investments are underway in solar, wind, and grid-scale electrification. This is not a case of giving up oil, but of hedging against its declining strategic centrality in the global energy system.

The motivation is clear. These countries understand that their long-term welfare depends on preserving the economic value of their fossil reserves by using renewables domestically and exporting oil at higher margins, rather than burning it to power air conditioners and desalination plants. Solar farms in the desert, green hydrogen projects in Neom, and cross-border electricity grids are not symbolic; they’re strategic.

Middle Eastern energy producers are not replacing oil; they are layering high-EROEI energy sources into their systems to improve efficiency, reduce internal entropy, and maintain fiscal and geopolitical room to manoeuvre as global energy flows evolve.

China is not alone in pursuing a surplus-positive, sovereignty-enhancing energy evolution. Even the world’s fossil fuel giants see the logic. What distinguishes China is the scale, speed, and systemic integration of its approach.

The EROEI Trap of American Energy Politics

Contrast this with the United States, which, despite talk of energy independence, is increasingly mired in an EROEI crisis of its own making.

For the past two decades, American oil production growth has come primarily from shale, which is a source with low and declining EROEI. Extraction requires horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing and constant reinvestment to offset rapid well depletion. Every incremental barrel now requires more energy, more capital and more environmental risk. And as shale fields mature, costs are rising faster than returns.

The U.S. has, in effect, mortgaged its future energy security on a finite, unstable, low-yield resource.

Donald Trump’s recent turn toward nuclear energy as the solution may seem like a way out. But nuclear’s EROEI (5:1 to 15:1 depending on methodology) is highly dependent on uranium supply chains and waste management systems, many of which are geopolitically fragile. An American pivot to nuclear means greater reliance on imported uranium, global enrichment capacity, and long-term geopolitical agreements, including with adversarial or unstable regions. It is clear that in this context, Trump’s America needs to normalise relations with Russia at a minimum, as Russia remains - and is likely to be, all other things being equal - a major supplier of uranium to the United States.

This is not sovereignty. It is exchange dependence masked as technological bravado.

The Fossil Federalism Bind

Energy policy in the U.S. is also structurally hamstrung by domestic political geography. The core of the Republican electoral map - the “red states” - is heavily invested in fossil fuel extraction. Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana and North Dakota: these states not only supply traditional energy but wield disproportionate influence due to the design of the Senate and Electoral College. Fossil fuels are not just an economic base; they are a political stronghold.

This creates a perverse feedback loop: as the long-term viability of fossil fuel EROEI declines, fossil states resist transition, using their political clout to preserve an increasingly energy inefficient energy regime. The result is national stasis. The U.S. is stuck defending an increasingly entropy-generating energy base for reasons of domestic electoral survival.

This is how historical energy abundance becomes a loadstone, weighing down national agility. What was once a source of power now traps the U.S. in an inefficient, internally contradictory posture: technologically innovative but energetically reactionary.

The American Ouroboros: Cannibalising Itself

The tragedy of the American energy system today is that it resembles an ouroboros - the ancient symbol of a serpent devouring its own tail. Once the global leader in energy innovation and surplus generation, the U.S. is now caught in a loop of internal cannibalism, where the very systems that once delivered abundance are now feeding on the nation’s ability to adapt and renew.

At the heart of this self-destruction lies entropy, not just in the thermodynamic sense, but systemically. As shale oil wells deplete faster and cost more to sustain, more energy and capital are being consumed just to stand still. The fractious and partisan politics of energy, coupled with the growing costs and inefficiencies of shale, drive increased government financial assistance to the industry. Meanwhile, domestic political structures have become increasingly hostile to energy innovation, trapped in nostalgia for a carbon-intensive past.

The ideology of energy dominance - once grounded in abundance - is now chained to grievance. Entire constituencies, particularly in fossil-rich red states, have come to view decarbonisation not as opportunity, but as betrayal. Climate change is cast as a hoax, allegedly concocted by China to weaken America. Environmentalism is treated not as a strategy for surplus renewal, but as a cultural enemy. Fossil fuel lobbyists ply their trade in the corridors of power. According to Open Secrets, the oil and gas sector undertook lobbying in 2024 to the total value of over $153m. This is a national pathology.

And so the system feeds on itself: more subsidies for declining fossil energy, more resistance to change, more polarisation and more institutional decay. Instead of climbing toward a higher EROEI energy plane, the U.S. risks sliding into a self-reinforcing loop of degradation, where political paralysis meets resource exhaustion. Initiatives that penalise moves to higher EROEI technologies have distributional implications in Realpolitik and sector terms, but also stymie geopolitical sustainability.

This is how empires decline, not with a single dramatic collapse, but through entropy disguised as tradition. And unless it breaks the cycle, America’s energy ouroboros may eventually consume the very foundations of its prosperity.

Strategic Lessons

Let us be clear: countries that possess abundant, easy-to-extract coal, oil and gas - and can maintain high EROEI - will continue to enjoy forms of energy sovereignty. Saudi Arabia, Russia and Iran are cases in point: their power is not just oil volume, but oil efficiency; that is, the capacity to extract large surpluses with minimal systemic strain. Russia also has abundant coal reserves, likely to be available at comparatively high EROEI rates for decades to come.

But this club is shrinking. For everyone else, especially major industrial economies, the strategic path forward lies in high-EROEI, renewable infrastructure.

China understands this. Its energy transition is not merely environmental, it is systemic. By upgrading the EROEI of its energy base, it is upgrading the resilience, sovereignty and productive potential of the entire system. China is not decoupling from global trade at all, but it is decoupling from relative global energy dependencies. It is replacing rent-seeking fossil circuits with stable, productive value loops.

This is not just about solar panels and wind turbines. It is about civilisational architecture on an economic base premised on high efficiency in energy mobilisation and deployment. It enables the building of an economic metabolism that thrives on surplus rather than survival, and one that creates value internally rather than constantly extracting it from abroad.

The central question of our time is no longer just “how fast is GDP growing?” or “what’s the inflation rate?” These are downstream metrics. The upstream question is: how much net energy does a system have at its disposal, and who controls it?

In this light, China’s massive renewable build-out is not just a green initiative. Rather, it is a strategic overhaul of the national energy metabolism. It is creating a surplus-rich, entropy-reducing, sovereignty-enhancing infrastructure for the next phase of its civilisational development. The U.S., meanwhile, is trapped in an EROEI decline spiral, held hostage by the configuration of domestic politics, legacy energy systems and ideological battles. Nuclear may offer a partial reprieve, but it introduces new layers of dependency. Fossil entrenchment, despite declining returns, continues to dominate the political landscape.

So yes, it’s energy, stupid. And more specifically, it’s net energy - the surplus that makes everything else possible.