My last post made reference to a book called Dying by the Sword, by Monica Duffy Toft and Sidita Kushi. This article is a slightly updated review essay penned earlier this year for colleagues.

A while ago, I finished Dying by the Sword (Oxford 2023), by Monica Duffy Toft and Sidita Kushi. The book deals at length with the key themes introduced in their article “Introducing the Military Intervention Project: A New Dataset on US Military Interventions, 1776–2019” (Journal of Conflict Resolution, August 2022) and discussed in a recorded seminar hosted by the Quincy Institute with John Mearsheimer as discussant. This seminar can be viewed here.

The Main Argument

The thrust of the book’s argument is that:

Since the U.S.’ founding in 1776, it has “become addicted to military intervention” (p. 5);

The U.S. today “pursues a whack-a-mole security policy — much more reactionary than deliberate, lacking clear national strategic goals” (p. 5); and

Should the U.S. “not abandon its addiction to force-first, kinetic diplomacy, it will do permanent damage to its vital national interests; including its diplomatic corps, economic influence, and international reputation” (p.,5).

The argument is well run.

It marshalls ample statistical data to support its broad sweep of U.S. foreign policy over the past 250 years or so. For mine, the most striking observation is empirical: between 1946-1989 the U.S. initiated on average 2.4 military interventions per year, rising to 3.7 instances on average each year between 1990-2019. It observed that in the period after the dismantling of the Soviet Union, when the US was actually at its most secure, the resort to “kinetic diplomacy” viz., military interventions actually intensified.

between 1946-1989 the U.S. initiated on average 2.4 military interventions per year, rising to 3.7 instances on average each year between 1990-2019.

Toft and Kushi point out that on most if not all occasions the target countries and populations were worse off by any measure post US intervention than before. In short, it is an excoriating expose of American militarism, its hubris and failures.

Reasons for Hope without Optimism

Set against the historic evidence, the authors argue that there is still time and hope to revitalise non-kinetic diplomacy over the ‘military first’ mantra. At best, I suggest that it is a hope that cannot be buttressed by any substantive optimism. I say this because despite the erudite exposition of American militarism over the ages, it’s what the book doesn’t address that is suggestive of a less sanguine possibility.

In sum:

The book underestimates the power of the military industrial complex. It acknowledges that it is part and parcel of why the military first doctrine has taken hold but offers no persuasive means of dismantling its tentacles of influence. The allure of profit and the symbiosis between the MIC and the USD preponderance is not considered at all.

The book also underestimates the cultural power of the ‘American Mission’ - that is the deep millenarian stripe that marks the American body politic, and which finds succour across the political divide.

The book underestimates the cumulative impacts of US and allied foreign policy on other countries, particularly with respect of:

Regime change efforts and the disruptive effects this has on the lives of ordinary people

US hypocrisy

The legacy of colonialism, and

The effects of USD denominated global finance, particularly how it is mobilised via the IMF to the detriment of debtor nations

The book overstates the benign character of the so-called ‘liberal international order’. Authors like Mearsheimer (who reviews this book favourably) and Porter have both demonstrated that there was little benign about the actual practice of the ‘liberal order’.

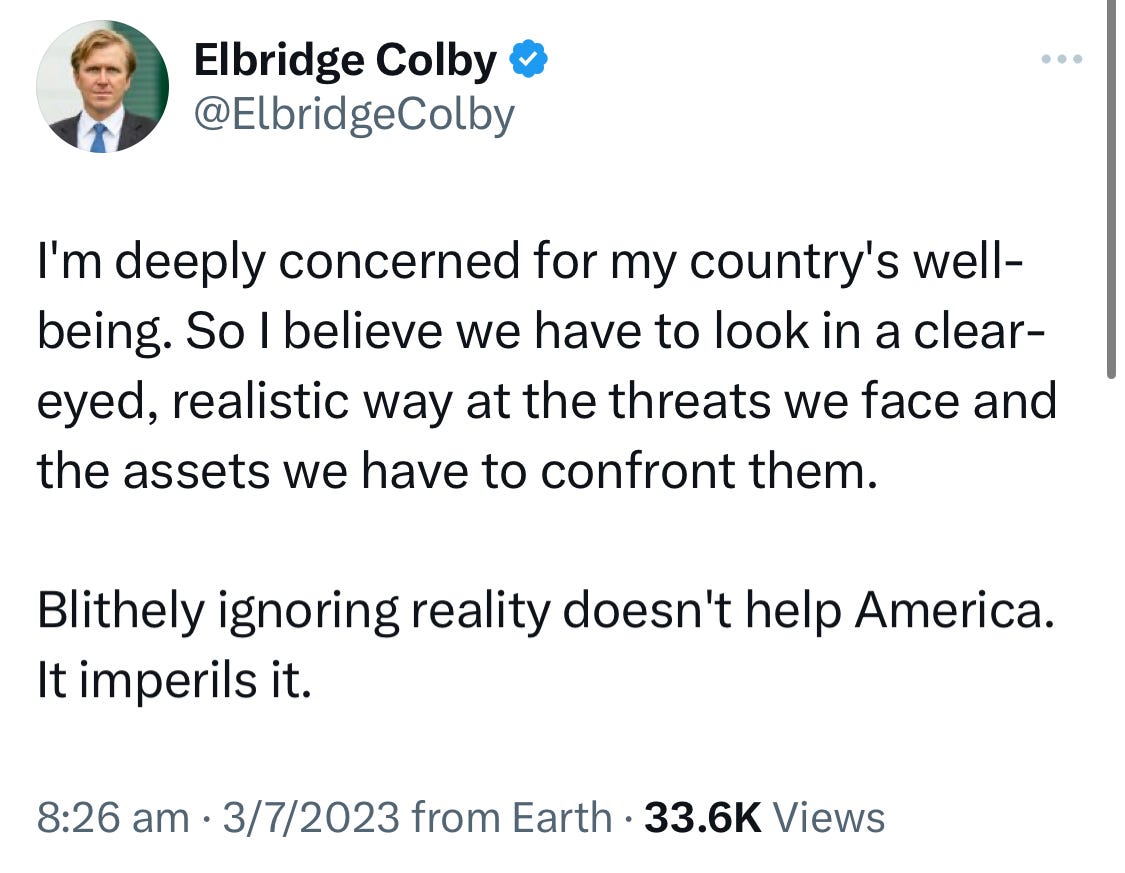

As a result, the book cannot fully understand or explain why the U.S. feels vulnerable all the time, despite its claims to benign goodness, let alone its hawks’ “endless confidence in US military might” (p. 12). Why is it that many in the United States, such as self-proclaimed ‘realist’ Bridge Colby (see Tweet image below, for example), with its self-claimed exceptionalism, its superior ideology, its superior military capabilities and insuperable ‘soft power’, feels perpetually at risk and vulnerable; so much so that preemptive military actions are increasingly justified?

John Mearsheimer recently (June 2023) gave an interview in which he reflected on the state of the collective western alliance in the context of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. In it, he says the bulk of the world is now in effect giving the US “the finger”. He says that the accumulation of belligerence, bullying, and sanctioning over half the world’s countries and general hypocrisy eventually come back to bite you “on the heinie” (click on the image to access the interview on YouTube).

Mearsheimer’s graphic terminology brings the entire edifice to its knees; at root, what Mearsheimer is describing is a reality in which American exceptionalism has undergirded its incessant propensity to intervene, and the vast majority of the world’s nations (and populations) have simply had a gut full. (Incidentally, despite these observations, Mearsheimer has a blind-spot when it comes to China, which is something I will write about on another occasion.)

Recent events (October-November 2023) in Gaza have compounded America’s broader reputation, as the Biden Administration’s original attempts to rationalise and in effect preemptively forgive Israeli attacks on civilians and civilian institutions in Gaza, painted the US into a public relations corner. Few across the world have accepted the arguments advanced by Israel and its supporters for its military actions in Gaza; most view it as an unjustifiable massacre at best, and genocide at worse.

Duffy Toft and Kushi conclude by arguing that “American exceptionalism blinds policy makers and citizens to strategic choices that ultimately harm both the United States and the world … and to “shift away from America’s militarism, the US foreign policy community and the body politic must assess and accept past successes and failures to begin to make amends” (p. 267).

This is well-intentioned but does not consider what it is that can actually break the “path dependency” that is reinforced by American exceptionalism. American exceptionalism and the millenarian zealotry and moral righteousness that comes with it cannot be broken via some reasoned acceptance of past success and failure. For the belligerent, failure is not only temporary; it is a function of insufficient effort and application.

For the hawks, who have “endless confidence in US military might” (p. 12) any episode of lack of success is due to insufficient might being applied. The remedy is always to apply more force.

To close this reflection, I am reminded of the friend-enemy distinction of politics, advanced by Carl Schmitt, the famous and controversial German jurisprudential theorist of the 1920s and 1930s. This distinction is what animates the passions that make conflict a possibility; it’s the transgression into a non-rational modality where ‘death’ is not just warranted but often celebrated. Duffy Toft and Kushi have an excellent grasp of the empirics of American militarism over the ages; if only it were matched by an understanding of the drivers of militarism itself.

Until American exceptionalism is dealt a blow, a serious blow, it will persist to animate the militarism that has created not only so much damage to the United States but to the victims of its belligerence across the world. Meanwhile a growing number of countries will continue to give the U.S. and its militaristic adventures “the finger”.