Dire Straits

Taiwan Island, American Displacement Anxiety, Thwarted Ambitions & Contemporary Asian Dangers

There’s been a rising chorus of mainly western voices about the imminent prospects of ‘war over Taiwan’. This essay aims to set this recent hyperventilation against a wider historic context. It traverses history, geopolitics and what can be called the ‘spiritual war’ and how these dynamics intersect the question of the unresolved Chinese Civil War. The role of the United States is never far away, unsurprisingly. The essay is a bit longer than usual, but I hope the content is sufficiently rich to aid our understanding of the issues.

The United States has embarked on a ‘repeat and rinse’ strategy in Asia, aimed at causing maximal disruption to regional peace in the pursuit of regional primacy. I say ‘repeat and rinse’, because as will become clear towards the end of the essay, the American game plan unfolding in Asia draws from the play book that was the centrepiece of US foreign policy in Europe in the years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union (1991). Just as the US strategy in Europe has led to the present tragedy and debacle on the steppes of Ukraine, so the Asia variation is not only reckless and irresponsible but dangerous to the welfare of the people of the region.

Remember, the United States is geographically not in either Europe or Asia, with its own citizens shielded by distance and geography. The US can, in effect, adopt an ‘all care no responsibility posture’; if things don’t pan out as planned, the US simply walks away. It wouldn’t first time.

The Island of Taiwan is one of the pivots or hinges in Asia. This essay aims to unpack this pivot and how it relates to US ‘grand strategy’ ambitions, historically and in the present. To summarise the key points and arguments:

Taiwan island in and of itself has no sovereignty status as a nation state. The island is part of a single Chinese sovereign territory. This is the position embedded in the Constitution of the Republic of China (ROC), the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), resolutions of the United Nations, and positions of the United States Government as articulated in various communiques and official documents. It’s also a position accepted by the overwhelming majority of countries around the world.

This status matters, because attempts to alter this status is one of the root causes of current frictions. Taiwan island remains subject to administrative dispute between two competing Chinese administrations. This stems from a not fully resolved civil war, dating back to the 1930s and 1940s. The status of the island can only be understood in the context of this unfinished civil war.

The US has long harboured ambitions to occupy and control the island for its own strategic purposes. This has seen the island positioned as a potential launchpad to prosecute either a geopolitical or at times a “spiritual war” against mainland (Communist) China; and at other times, the island has been a bulwark protecting America’s Lake - namely the greater Pacific Ocean.

Today, the US is fanning regional instability in Asia through the application of strategies employed in recent times in Europe. Taiwan island is at the epicentre of this destabilisation. The ‘rinse and repeat’ approach increases the risk that the US is seeking to lead Asia down the same Primrose Path that has seen the progressive destruction of Ukraine.

Resolving the Chinese civil war is a necessary condition for regional stability. It’s a civil war demanding resolution from the warring parties. The question is, will it be resolved peacefully or not; and what are the conditions of such a resolution?

The status and role of Taiwan Island

Status

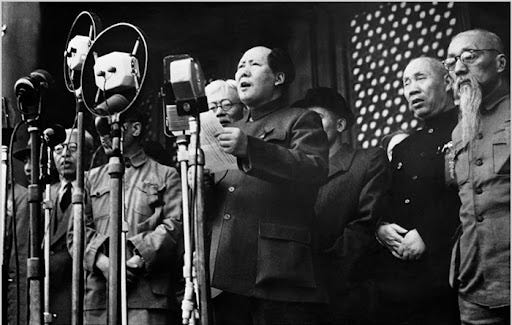

The Island of Taiwan in and of itself has no sovereignty status as a nation state. It is a territory that’s part of China - whether that’s the Republic of China (ROC, founded 1912) or the People’s Republic of China (PRC, founded 1949). Put plainly, the island of Taiwan is the sovereign territory of a single China; it has no sovereign status of its own. It is subject to jurisdictional dispute arising from and as a continuation of the unfinished civil war, which saw the Community Party of China prevail over much of the territory of China, declaring the founding of the People’s Republic of China on 1 October 1949. The PRC and ROC are mutually exclusive; they do not recognise each other but claim sovereignty over more or less the same territory.

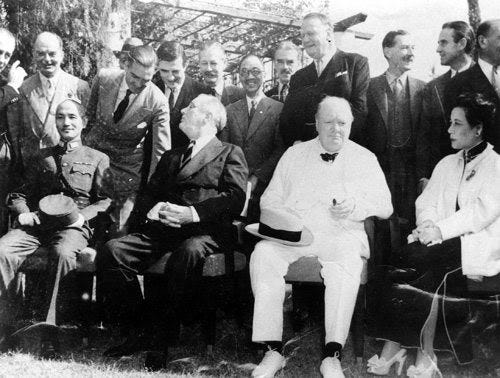

From 1895 to the end of World War 2, Taiwan island was occupied by Japan. However, the post-war status of Taiwan was the subject of discussions and decisions embodied in the Cairo Declaration, coming out of a conference held in Cairo in November and December 1943. According to the US State Department archives, at that time:

“U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with Chinese President Chiang Kai-shek and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in Cairo, Egypt, to discuss the progress of the war against Japan and the future of Asia. In addition to discussions about logistics, they issued a press release that cemented China's status as one of the four allied Great Powers and agreed that territories taken from China by Japan, including Manchuria, Taiwan, and the Pescadores, would be returned to the control of the Republic of China after the conflict ended” (emphasis added).

This is what subsequently happened upon the unconditional surrender of Japan.

Put plainly, sovereign jurisdiction over Taiwan island was to be returned to the ROC at the end of the second world war. (A key word here is ‘returned’ as this denotes clearly a recognition that prior to Japanese occupation, Taiwan island was part of China.)

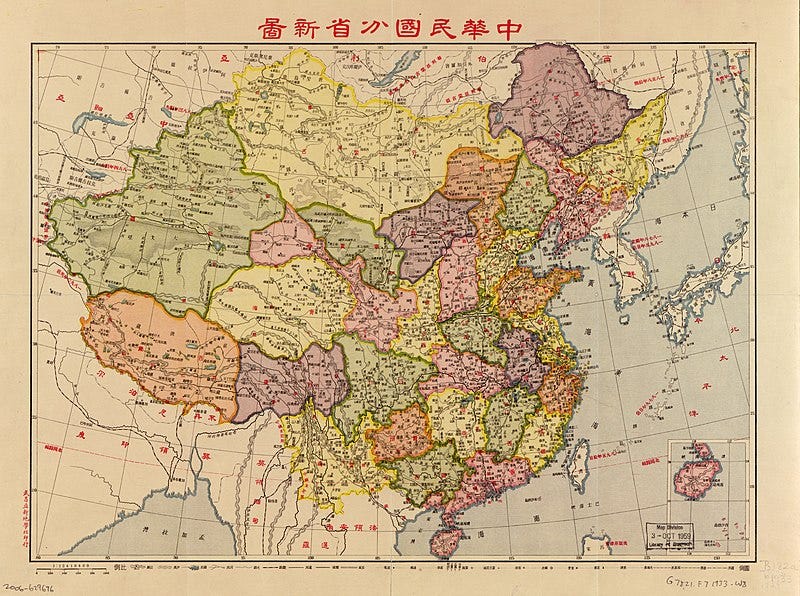

The ROC continues to this day - through its official cartography and constitution - to claim jurisdiction over a single China whose territorial scope can be traced back to the pre-1949 period. (In recent years, the ROC has relinquished certain claims to sections of land in the Himalayas and Mongolia.) I will show a sample of ROC maps below, though the aim isn’t to begin a detailed cartographic argument, particularly as they relate to the South China Sea, but to simply show the continuity that extends from the 1930s to the present day insofar as the ROC territorial claims are concerned. By doing so, I aim to remind those less familiar with the historic conditions that there is only ‘one China’, even as there remains remnant jurisdictional disputes over some portions of this China - namely Taiwan island and a few other smaller islands.

The first map shows the ROC territories and provinces, from 1933. The island of Taiwan is depicted as part of Fujian province. This predates the foundation of the PRC.

Map 1: Republic of China Map c. 1933

The second map is from 1946. It isn’t much different. Note the claim over Mongolia.

Map 2: Republic of China c. 1946

The third map is a contemporary one. Again, it isn’t that different from previous maps. The point to note is that from the ROC’s point of view, there is also only one China; and that this one China includes the territories of Taiwan island as well as those of the mainland.

Map 3: Republic of China (c. 2022)

The fourth map identifies areas claimed by the ROC as part of one China that are overlapping with territories under the sovereign jurisdiction of other nations.

Map 4: Republic of China and Territorial Disputes (current)

Without labouring the point, the PRC territorial jurisdiction is somewhat smaller than that claimed for one China by the ROC. The most obvious differences are precisely those areas under the sovereign jurisdiction of other nations as noted in Map 4. The PRC has resolved most of those disputes. The issue of the so-called “nine dash line” and the South China Sea is another matter, though again it can be noted in passing that the current “nine dash line” is adhered to both both the PRC and ROC, with the line’s genealogy dating back to the “11 dash line” claimed by the ROC.

A Launchpad to Reclaim the Mainland

The ROC was overthrown as a result of the civil war conducted between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Communist Party of China (CPC). The successor to the ROC, the PRC, was declared on October 1, 1949 (image below). The civil war, however, remains un-concluded, with no formal ceasefire or armistice.

In late 1949 and early 1950, remnants of the ROC, under the auspices of the Kuomintang (KMT) led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, fled to the island of Taiwan, from which they sought to rebuild their forces to reclaim the entirety of China with the aid of the United States. American provision of military aid to the ROC was formalised in December 1954 by way of the Sino-American Mutual Defence Treaty. The ROC military was reformed. Conscription was modified to provide a reserve. Former Japanese soldiers (known as the White Group) were enlisted to provide training and planning assistance, though Japanese assistance to Chiang was already prevalent as early as 1949. The local Taiwanese population was Sinicised through intensive propaganda to support conscription and mobilisation efforts. The aim, as articulated in 1956, was to mobilise a force of 730,000 men aged 17-31 years of age to support an invasion of the mainland.

During the early 1950s, the ROC periodically attacked the mainland coastline from ROC controlled islands, with its CIA-trained Anti-Communist Salvation Army. Indeed, the ROC even offered to attack the PRC during the Korean War period, but these overtures were declined by the US. The ROC continued to actively explore other strategic options to create diversions, such as destabilisation campaigns on the PRC-Myanmar border or guerilla involvement in the Vietnam War, so as to clear the way for an ROC invasion of the mainland across the Taiwan Strait.

In the 1960s, the KMT prepared Project National Glory, a large-scale invasion plan of the mainland. The Project never came to fruition, and was abandoned in 1966. The Project National Glory planning organisation was abolished in 1972. The KMT-ROC formally abandoned the use of force to reunify with the mainland in 1991. But - and this is an important ‘but’ - the claims to one China, albeit an ROC version of one China, have never been renounced.

From Launchpad to Bulwark

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the ROC sought American assistance to mount its various invasion and reclamation plans. It has generally been recognised by historians that these overtures were rebuffed; the US had its hands full elsewhere and were not supportive of opening another front. Despite the reticence of the US, upon the onset of the Cultural Revolution (1966), Chiang Kai-shek was adamant that conditions for an invasion of the mainland were propitious. Chiang was readying for a deteriorating situation on the mainland, believing that instability would undermine the CPC regime. He reached out again to the US for support; again, it was rebuffed. The U.S. was already deeply occupied in other parts of Asia, and some in the political elite were contemplating a major realpolitik move to switch from the ROC to the PRC as part of a wider effort to outflank and isolate the Soviet Union.

As much as there remained ROC / anti-communist diehards in the U.S., their influence at the time was constrained by pressures elsewhere in the Cold War. The diehards would have to wait for another day. As I discuss below, this day has, for them, finally come again.

By 1969, the explicitly offensive posture that framed ROC-KMT strategy since 1949 had given way to a combined ‘Unity of the Offensive and Defence' strategic position. This more ambiguous posture was eventually replaced with an explicit defence posture, after the establishment of the Guidelines for National Unification in 1991. At this time, the ROC effectively abandoned the strategy of retaking the mainland with military force, as argued by Takayuki Igarashi in a 2021 research paper. Of course, by then, the ROC had long lost formal American recognition, and that of the United Nations.

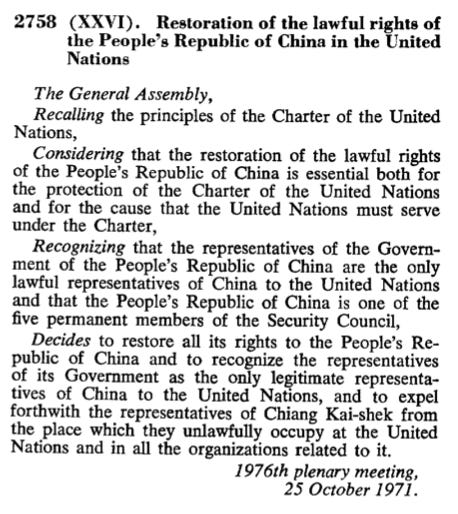

Recognition

For nations recognised through the United Nations, there is only one China. The overwhelming majority recognise the PRC as that single China; a shrinking number of countries continue to recognise the ROC. The United States originally recognised the ROC, stemming from the pre-1949 period, as did the United Nations. However, the United Nations withdrew the recognition of the ROC and recognised the PRC instead when it passed Resolution 2758 on October 25, 1971. The US eventually terminated this recognition and turned to recognise the PRC instead in 1979. The Joint Communique between the United States and China of February 27, 1972 laid the groundwork for this recognition.

The Shanghai Joint Communique

The Shanghai Joint Communique between the United States and China is a pivotal diplomatic instrument in the history of US-China relations. It was issued at the conclusion of the Nixon visit to China in 1972. On the question of the status of Taiwan island, the Americans, in the Joint Communique, had this to say:

The United States acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China. The United States Government does not challenge that position. It reaffirms its interest in a peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question by the Chinese themselves. With this prospect in mind, it affirms the ultimate objective of the withdrawal of all US forces and military installations from Taiwan. In the meantime, it will progressively reduce its forces and military installations on Taiwan as the tension in the area diminishes. (Emphasis added)

The relevant section is reproduced in the image below.

The Americans acknowledge that “all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is part of China”. This is an unequivocal statement of acknowledgement of two important points. First, both sides of the Taiwan Straits have the shared de jure status of being “Chinese”; second, all Chinese share the view that there is one China and that Taiwan is a part of this single China. In other words, there is no claim that Taiwan has a distinct sovereign status separate from China as a whole. The American Government “does not challenge this position”.

United Nations Resolution 2758

The UN Resolution 2758 was passed on October 25, 1971. is reproduced in the image below. Multiple language downloads can be accessed here. It has in recent times become the subject of some controversy, discussed below.

Note that the Resolution recognised “the representatives of the government of the People’s Republic of China as the only lawful representatives of China to the United Nations …”. The resolution is clear that there is only a single China, and that the PRC is “the only legitimate representative of China to the United Nations”. There is one China; the resolution switched recognition of which one China was formally recognised. Further, all rights are restored to the PRC. There can on this formulation only be one China with one set of relevant rights vis-a-vis representation at the United Nations and “in all the organisations related to it”. The rights are not divisible.

The ROC Constitution

The ROC Constitution was adopted on December 25, 1946, by the National Assembly convened in Nanking. It was promulgated by the National Government on January 1, 1947, and put into effect on December 25 of the same year. In it, there are at least 28 references to “province or provinces”, reflecting the territorial purview of an entire China, as depicted in the maps discussed above.

Until 1990 the ROC maintained a policy of mobilisation aimed at retaking the mainland. When this period of mobilisation came to an end, the ROC Constitution was supplemented with the Additional Articles of the ROC Constitution, taking effect on May 1, 1991. These Additional Articles introduced the legal concept of the “Taiwan Area of the Republic of China”. This has also been known as the “free area of the Republic of China”, the “Tai-Min Area (Taiwan and Fuchien)” or the “Taiwan Area”. These additions refer to the geographical territories actually under the control of the ROC, and were made to reflect the realities of the ROC and the political status of Taiwan island “prior to national reunification”.

The Original ROC Constitution has been amended seven times. At the last amendment, in 2005, the following provisions were included:

The territory of the Republic of China, defined by its existing national boundaries, shall not be altered unless initiated upon the proposal of one-fourth of the total members of the Legislative Yuan, passed by at least three-fourths of the members present at a meeting attended by at least three-fourths of the total members of the Legislative Yuan, and sanctioned by electors in the free area of the Republic of China at a referendum held upon expiration of a six-month period of public announcement of the proposal, wherein the number of valid votes in favour exceeds one-half of the total number of electors. (Emphasis added)

The key point for the purposes of this essay is the first; namely that the territory of the ROC is defined by its existing national boundaries. Note that these boundaries are those reflected in the maps discussed above. The provision references the “free area of the Republic of China” as the applicable spatial catchment defining voter eligibility, in the event of a proposal to alter the national boundaries. I will return to the question of lawful mechanics below.

Summation

From the point of view of the ROC itself, Taiwan island is one subordinated territory (with distinct characteristics - namely it is described as the “free area”) within a larger single China. This has been a consistent position for decades and also finds concordance in the UN position (pre and post 1971) as well as in the early utterances of American administrations prior to and subsequent to the formal recognition of the PRC.

All of this is de jure reality. This de jure status remains in place to the present. The jurisdictional status of Taiwan as a provincial territory of a single China has not changed. This position is one that is not only claimed by the PRC but is also “not challenged” by the Americans in their formal declarations nor is it challenged constitutionally by the ROC.

Again, there is, finally, no mutual recognition of the PRC by the ROC or vice versa. They are mutually exclusive, each claiming sole, lawful and legitimate jurisdiction over the one China. In other words, from each of their perspectives, there can be no ROC and PRC; it’s one or the other. For 180 out of 192 nations, the PRC is the sole and legitimate government of the one China. Twelve countries continue to recognise the ROC as of today.

US attitudes towards Taiwan and China

So much for de jure realities. As important as these are to stabilising the relations between states, it is also clear that the American attitude towards Taiwan Island isn’t reducible to grudging acceptance of the realities of one China of which Taiwan is a part.

Rather, the United States has always coveted control of Taiwan Island and has historically adopted somewhat ambiguous attitudes towards how serious they would abide by official policy doctrine. The rationale for this desire varied over time, as either a bulwark against incursion into America’s lake - that is, the greater Pacific - or as a launchpad, from which it could attack mainland (Communist) China. And, I will argue shortly, there was also something highly metaphysical so to speak about Taiwan Island, in terms of America’s posture towards China and its broader ambitions.

Realpolitik

From a purely geopolitical and force projection point of view, the island featured in US planning well before the end of World War 2, and certainly before the escape to Taiwan island by the defeated ROC-KMT forces in 1949 and 1950.

In the early 1940s the US State Department and Department of Defence began considering the future of Taiwan island, and America’s role. By mid-year 1942, the KMT made clear their expectation that Taiwan island would be returned to ROC (Chinese) sovereignty post-war. The then director of the Eastern Asiatic Affairs Department of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Dr Yan Yun-chu, made clear that the return of Taiwan island was appropriate as its population was largely Chinese and that, over time, the island had maintained close connections to the Chinese mainland. Within a year, this privately expressed sentiment was being amplified publicly, perhaps as a response to suggestions being made in the American media that Taiwan island should be placed under an “international mandate”.

The Cairo Declaration in effect confirmed that the island would be returned to ROC jurisdiction. That said, the US preferred a US-led military administration with delayed handover of full sovereignty. Put plainly, the KMT was not well regarded by the Americans at the time. During the course of the second world war, the US had formulated both a plan of conquest and a plan of occupation for Taiwan island. While neither of these plans materialised, the planning showed just how significant an asset the island was strategically. The island was considered to be a critical military asset, no doubt, and while plans were drawn up to attack the Japanese bases on Taiwan, American agencies were also considering the challenges of future occupation of the island. By the middle of 1944, arrangements were put into place to train personnel specifically in anticipation of a planned occupation of the island. The US Navy was mandated to plan and administer the civil affairs of the island during the planned occupation, though it was the army that was expected to provide the majority of the personnel. Training of these personnel at Princeton University was scheduled to begin October 1, 1944.

While this planning and preparation was taking place, in the Spring (northern hemisphere) of 1944 news reached Washington that the KMT had formed a provisional government for Taiwan in Chungking (Chongqing) and were preparing to administer the island as a separate province. While the US did not expect the KMT to establish any form of government prior to the planned US occupation, there was sufficient concern amongst American policy makers as to the need to ensure US preeminence. The Americans did not believe the Chinese, under the leadership of the KMT, had the military wherewithal to force the surrender of the Japanese; nor was it believed that the KMT was well-equipped to administer the island upon the collapse of the Japanese. While the transfer of sovereignty of the island - as per the Cairo Declaration - was never disputed, there were debates about exactly how and when such a transfer would be made.

The State Department and the Department of Defence were at odds with each other as to whether the planned American occupation of the island should be fronted by the KMT at all. While input and advice from the Chinese was seen as politically necessary, the Americans were at pains to “prevent unwelcome participation or interference by the Chinese” and declared that “strict insistence on the exclusive responsibility and authority of the American military authorities be maintained” (US Department of State Records, quoted in Leonard Gordon (1968) ‘American Planning for Taiwan, 1942-1945’ in Pacific Historical Review). (The account above draws heavily from Gordon’s paper.)

The military strategic significance of the island was amplified in the post-war years as the US sought to consolidate America's Lake - namely, the greater Pacific Ocean - and mitigate risks of the USSR posing a threat to American primacy in the Pacific and its foothold in other parts of Asia, such as Korea. This was evident in Presidential level discussions entertained about the situation in Korea in June 1950. A classified memo, prepared by General Douglas MacArthur, was circulated as part of this meeting, which described Formosa (the island of Taiwan) as an “unsinkable aircraft carrier and submarine tender”. Should the island fall into the hands of the Soviets, the memo went on to argue, “Russia will have acquired an additional “fleet” which will have been obtained and can be maintained at an incomparably lower cost to the Soviets than could its equivalent of ten or twenty aircraft carriers with their supporting forces.” Control of Taiwan island was, in this context, a critical bulwark to thwart Soviet risks in the Asia Pacific.

Realpolitik was to further intervene in America’s posture towards the ROC in the late 1960s, culminating in the moves towards formal recognition of the PRC instead of the ROC. Kissinger and Nixon’s storied visits are well known, as is the fact that the opening up of dialogue with Beijing was driven largely by a strategic desire to gain leverage over the USSR. Kissinger articulated the underlying strategic thinking in an interview in Time Magazine in December 1970. He noted that the Soviets were interested in a dialogue with the US to reduce distractions on the “western front” so that they could address the Sino-Soviet border conflict in the east. Merely by letting Moscow know that the U.S. was “restudying the China question” the U.S. was able to secure considerable leverage vis-a-vis the Soviets. The dialogue with Beijing was, in the first instance, envisaged to act as a counterweight to the USSR.

Spiritual War & The Loss of China

The defeat of the KMT by the CPC was not only a geopolitical bodyblow to the U.S., it was also a metaphysical kick in the guts. The “loss of China” to the Communists opened domestic political scabs as the Truman administration was pilloried for its ineptitude in the years after the end of world war 2.

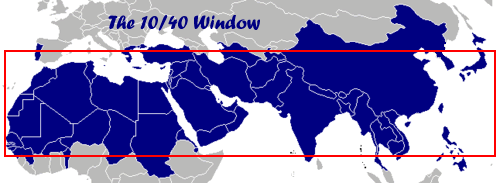

From the late 1800s and well into the first quarter of the 20th century, American Christian Missionaries trained their sights on China’s population as one of two remaining targets for salvation. The influx of missionaries to China was bound up with a neo-colonial missionary project that extended from civil religious nations of America as a saviour nation. This mission aimed at overcoming the last vestiges or strongholds of demonic power in what, as described by Rene Holvast (2009), was known as the 10/40 Window - the space between the 10th and 40th parallels where Christianity was yet to take a foothold and was at its weakest. The 10/40 Window covered North Africa, the Middle East, India, China and Japan. This missionary zeal saw a rapid expansion of the presence of missionaries in China until the 1940s. By the early 1950s, however, after the founding of the PRC, some missionaries concluded that it was no longer viable to stay in China and in due course, Christian missionaries were prohibited in China at large and expelled. Those that did not return to their home countries found their way to the island of Taiwan with the retreating KMT forces or to Hong Kong.

The Christian missionary dimension of America’s commitment to Taiwan was embodied by the fact that Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and his wife were baptised in the 1920s, which endeared them to many Christians in America. This Christian link was readily allied with the the politics of the years immediately after the establishment of the PRC. In castigating what he believed to be John H. Service’s capitulation to the communists - as part of a wide ranging speech on communists in the U.S. State Department - McCarthy observed in a 1950 speech that,

“When Chiang Kai-shek was fighting our war, the State Department had in China a young man named John S. Service. His task, obviously, was not to work for the communization of China. Strangely, however, he sent official reports back to the State Department urging that we torpedo our ally Chiang Kai-shek and stating, in effect, that communism was the best hope of China.” (Emphasis added)

McCarthy had begun his fabled mission to expose communist influences in the U.S. - the “enemies within”. The intersection between his anti-communist crusade and the dynamics of the war over China ultimately dovetailed with the great American lament that China “was lost”. The 1950s saw a virulent politicisation of the defeat of the KMT by the Communists in American electoral politics, which framed America’s interests not only in geopolitical terms (anti-communism) but in spiritual terms. McCarthy argued in that same speech that,

“Today we are engaged in a final, all-out battle between Communistic atheism and Christianity. The modern champions of Communism have selected this as the time. And, ladies and gentlemen, the chips are down– they are truly down.”

The chips were down because of treachery. The “loss of China” was both a domestic problem - traitors in our midst - and a worldly blow: Christianity on one side and Communistic atheism on the other. These Millenarian eschatological undertones, mixed with the zealotry of Manichean certainty, would animate an intense spiritual war as part of the wider Cold War environment. The spiritual war took spacial shape via the 40/10 frame, which defined regions of the world in which evangelical Christianity was thought to be underrepresented and weak. Conversely, therefore, these regions of the world - which included China - were the dominion or strongholds of powerful demonic forces. Such forces had to be dethroned to enable evangelisation to take place, ideally before the year 2000 (see O’Donnell). The territorialisation of the spiritual war buttressed the geopolitical-cum-ideological predilections of the time, forming a powerful concentration of forces that continue to play critical roles in American attitudes toward China (and the island of Taiwan) today. For ardent evangelicals, territorial conversion presaged the building of God’s kingdom on earth and laid the groundwork for the climax of Christ’s return.

Taiwan island figured strongly in this territorial-spiritual configuration. In a speech delivered in the US to a Christian Congregation in early 1958, by a former ROC Ambassador to Japan, the question was posed: “what can Christians in America do for China?” He was there seeking to rally American Christian support for the ROC in its ongoing efforts - at the time, as noted earlier - to retake the mainland. He intoned:

“Communist China, in its diabolical endeavor to uproot true Christianity, has wiped out in less than a decade the missionary work done by Western Christians during the last one hundred years. It has hounded and driven from China the dedicated American men and women who have devoted their lives to foreign missions.”

He quoted favourable the words of an (unnamed) American missionary who had, in 1957, claimed:

“True Christianity cannot do business with the stooges of the Communists, or be a party to the Communist use of the church for propaganda purposes... The line against Red China must be held. We must work and pray for the liberation of Red China and the opening of the doors again for missionaries.” (Emphasis added)

The politics was no ordinary politics; it was fundamentally one of a spiritual war. He argued that America’s interests, insofar as they are the interests of Christian missionaries, was to enable the recapture of the mainland by supporting the forces at work on the island of Taiwan. He thus argued that:

“Fortunately, while the Christian church stands in ruins in mainland China, it is surviving strong and confident in the province of Taiwan, which is now the seat of the Government of the Republic of China. The years of separation from the mainland have seen the Christian church in Taiwan advancing by leaps and bounds.”

Taiwan was clearly seen as a remnant of better days, but also a sign of better days in the future. In the decade since the communist victory, and the purge of missionaries from the mainland, the “province of Taiwan” was a refuge in which Christianity could develop and flourish. To illustrate just how much Christianity had flourished on the island, he provided some statistics. He tells his listeners that:

“In 1945, when Taiwan was returned to China after a half century of Japanese rule, there were less than 30,000 Christians on the island. Only a few denominations were allowed to operate, the most active being the Canadian Presbyterian Mission. Today, over 100 Christian denominations are operating in Taiwan. Within the space of 12 years, Christian membership has increased from 30,000 to nearly ten times that number.”

He evidenced that 10-fold expansion of the Christian congregation on the island in the mere space of 12 years. Note, incidentally, his recognition that Taiwan was returned to China by the Japanese at the conclusion of the second world war.

For him, Taiwan was a Christian beacon. He would describe an “average Sunday” in the Shih Ling Church that he would attend in Taipei, where:

“… you will see in the pews such prominent persons as President and Madame Chiang Kai-shek, Prime Minister and Mrs. O. K. Yui, Chief Justice Wang Chung-hui and his wife, Secretary General to the President and Mrs. Chang Chun, Chief of the Combined Service Forces and Mrs. J. L. Huang, and others high in the political life of the Republic. There is no country in Asia today where more outstanding government leaders are active Christians than in the Republic of China.” (Emphasis added)

He explicitly linked the propriety of the Government with its spiritual orientation, and pointedly observed that Chiang Kai-shek and his wife were prominent participating parishioners. Taiwan was a spiritual bastion, and a platform from which the Christian mission could again be launched to reassert the missionary presence on the mainland. The anti-communist battle was also a Christian rallying cry. Taiwan was not just an unsinkable carrier to be kept out of Soviet hands; it was the platform from which the spiritual war in China could again be prosecuted.

Repeat and Rinse; Variations on a Dangerous Theme

The Taiwan lobby has been an ever-present feature of Washington’s political set-up, though it has clearly experienced episodes of rising and falling influence. However, the lobby - and its Christian affiliations - has persisted. While the lobby’s influence waned during the 1970s through to the 1990s, it appears that in recent times conditions have ripened to enable it to make something of a comeback.

As I have suggested, the U.S. has always seen the island as either the launchpad or the bulwark of its interests, depending on the era. As a launchpad, it is there to enable the prosecution of the kinetic & spiritual war, traces of which go back to the late 1800s. Chiang Kai-shek was “fighting our war” (a Christian war) and the loss of China in 1949 was seen as an unforgivable betrayal of the U.S. by the Chinese.

The “loss of China” has played on the U.S. political elite ever since. Recognition of the PRC served a purpose but it’s clear the U.S. views the recognition of One China as a perfunctory Realpolitik interlude. It’s been salami slicing and weasel wording its way back since. The U.S. has always had a partisan view about the Chinese civil war - it backed the Nationalists who’ve now morphed into the general ensemble of “Taiwan / ROC”, which is both launchpad and bulwark. The U.S. has supplied arms to the forces on the island, more or less non-stop despite commitments to not.

There are grounds to believe that some, a vocal some, in the US political establishment see the island of Taiwan as unfinished spiritual war business. The diehards have bided their time, but sense that their time has come - or perhaps, that time is running out.

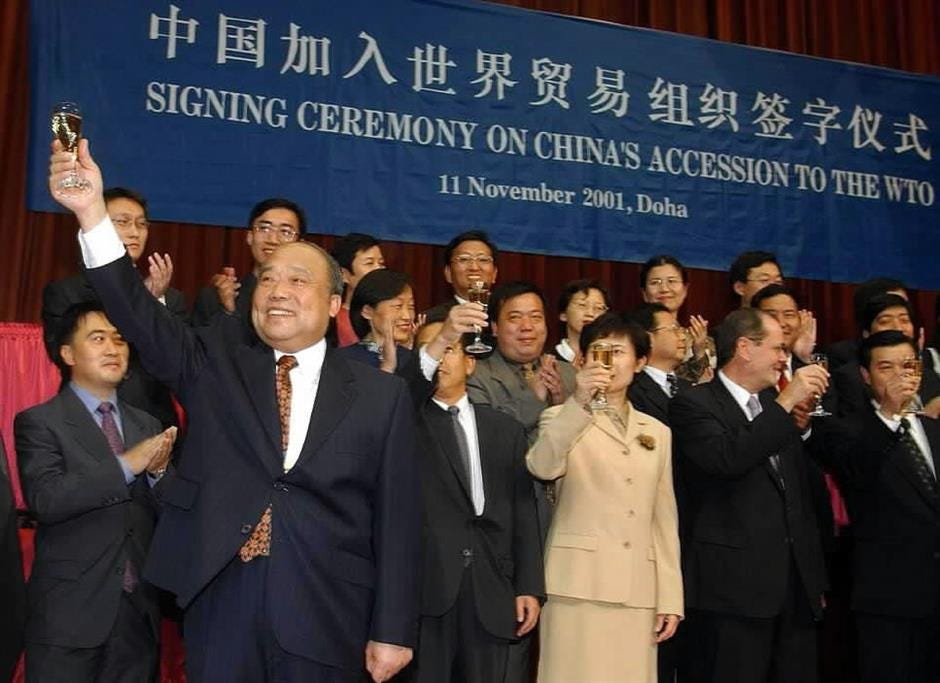

In the mid to late 1990s, the U.S. extended its engagement with the PRC and, in the process, continued to pursue efforts to change China. Whereas the evangelicals and missionaries explicitly pitted Christianity against atheistic communism, the ideologues of the 1990s prosecuted the spiritual war via economic means. By entangling China into the institutions of post-Cold War Pax Americana globalism the hope was that China could be transformed in America’s image. Clinton argued strongly for this, manifesting as inclusion in the WTO, on grounds that enforced economic liberalism would lead to political change in ways that favoured the U.S. Others at the time opposed this line of reasoning, but failed in their efforts to block China’s accession to the WTO in November 2001. Engagement via economic liberalism was expected to transform China in America’s image and in America’s favour.

Some 17 years later, Campbell and Ratner expressed buyer’s regret by 2018 when they lamented the failure of engagement. Campbell and Sullivan (2019) argued that “[t]he basic mistake of engagement was to assume that it could bring about fundamental changes to China’s political system …” And Jake Sullivan - now the White House’s National Security Advisor - confirmed this in remarks in February 2024 when he reflected on the failure of efforts over decades to change or mould China.

The spiritual war that had taken an economic-cum-political form between 1996 and 2018 was to be abandoned. China didn’t become like the U.S. The spiritual war had to shift gear, from one of salvation to an explicitly eschatological register. The spiritual war against demonic forces was again working its way through American discourse vis-a-vis China. If Chinese souls could not be saved, then China had to be vanquished. American policy towards the PRC is reprising the militarised evangelical mode that bear the marks of McCarthy and others, with China variously demonised as a threat. Here, China is the prophesised seven-head dragon from the end times, and the “King from the East” (on which see Eugene Bach’s China and End-Time Prophecy: How God Is Using the Red Dragon to Fulfill His Ultimate Purposes).

America’s pursuit of regional instability is a function of chronic displacement anxiety. Coming off the sugar high of the 30 year unipolar moment, the U.S. political establishment is incapable of dealing with a multipolar reality. Rather, primed with the zealotry of missionaries, the U.S. is embarking on a modern day ‘spiritual war’ that frames others as Evil. Millenarian prerogatives and manichean frames make detente an unconscionable dirty word. If the Evil could not be saved then they must be vanquished.

The playbook first tested and refined in Europe is not being adapted in Asia:

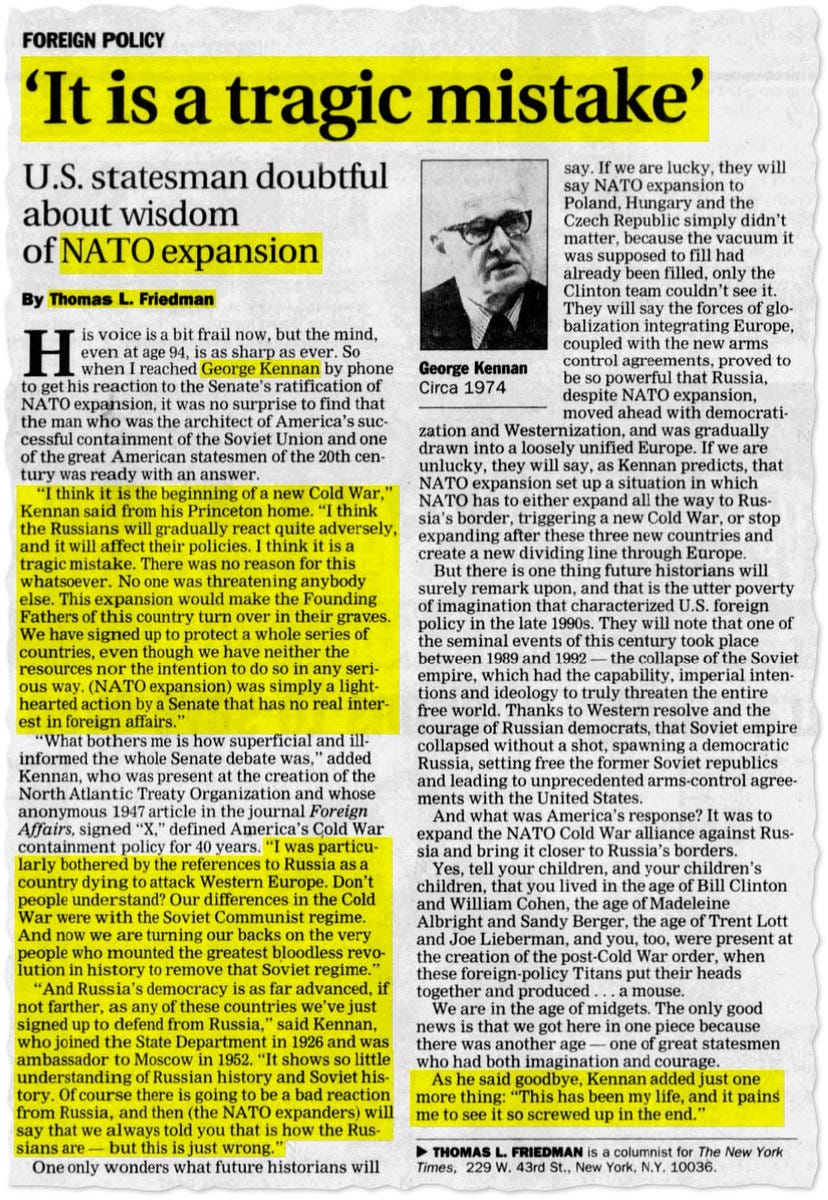

In Europe, NATO expansion eastward intensified insecurities, provoking reaction from Russia. It was described by George Kennan in 1997 - a storied American diplomat - as “the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold War era.” In Asia, instead of NATO expansion, the strategy of security encroachment is achieved through an extensive network of US military assets in Asia combined with a recent flourish of establishing minilateral defence agreements with subimperial allies, former colonies and client states.

In Europe, pressure on Russia was created and exerted through the application of economic sanctions. The same is being done in relation to China, first by way of the trade war launched in 2018 followed by various rounds of sanctions and export controls aimed at constricting Chinese economic and technological development.

In Europe, the liminal zones around Russia were destabilised via colour revolution and regime change initiatives. In Asia, we see this take place in Hong Kong, Thailand, Myanmar and other countries on China’s periphery. In a detailed study, Boston University academic Lindsey O’Rourke counted 64 separate regime change efforts initiated by the US between 1947 and 1989.

In Europe, NATO expansion enabled the intensification of military asset deployments aimed at key Russian assets. This includes missiles and the training and equipping of military forces on Russia’s peripheries. In Asia, the US has been arming and training forces on Taiwan “to the teeth” (BBC, November 6, 2023), and continues to exert an outsized military influence across the region. The U.S. has favoured a ‘kinetic first’ approach to international engagement (or force projection), with military interventions increasing in number and intensity in the years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

In Europe, the US and its allies built pressure on Russia’s maritime peripheries - particularly the Black Sea and Sea of Azov - via active military / aerial and naval activities ostensibly in international air- or sea space. The same is happening in Asia, in the name of ‘freedom of navigation’ in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait.

In Europe, extensive information wars have been prosecuted for decades. This has aligned with efforts to destabilise Russia itself and its peripheries, through the ‘work’ of US-funded NGOs. The US has explicitly committed funds to enable disinformation campaigns to be run against China. A recent investigation has exposed a Pentagon-orchestrated misinformation campaign against Chinese vaccines during the COVID pandemic.

In Europe, the US and its allies have ignored agreements entered into with Russia. This not only goes to the agreements to not expand NATO eastward, but also to agreements concerning the settlement of the conflicts in Ukraine known as the Minsk Agreements. The Minsk Agreements were ratified by the UN Security Council, and Germany and France were co-signatory guarantors. We now know that none of the western signatories had any intention of enforcing the agreement. In Asia, we are witnessing a back-tracking and salami slicing of commitments made concerning One China. Of course, the continued provision of arms to forces on Taiwan by the U.S. runs contrary to commitments made many decades ago, but recent backtracking is a little less ‘kinetic’ but nonetheless noteworthy. There is an emerging campaign to revise the idea of ‘one China’ and parse words to suggest that Taiwan island is effectively or de facto a sovereign nation in its own right; and therefore, the PRC does not have sovereignty claims to the island.

Hic Rhodus, Hic Salta … the decisive moment?

Have we reached the time in which the ‘decisive question’ becomes unavoidable? When, perhaps, the eschatological moment requires a resolution?

The decisive question goes to the resolution of the unresolved civil war.

This moment of decision is fraught and pregnant with potential violence, though violence is not an inherent deux ex machina. That remains a choice.

There are four possible outcomes, broadly speaking. They are:

The status quo, which by the nature of reality remains a fluid rather than a fixed state;

Peaceful reunification;

Forceful reunification; or

Two separate countries.

Two countries (4) will not happen peacefully. It will only be a theoretical possibility in the event of failed attempts to resolve the dispute via (3) forceful reunification. But rather than (4) the result of an inconclusive (3) may simply be a new status quo (1). Between (2) and (3) there are many ‘tactical’ permutations. The precise form of a single unified China vis-a-vis the governance arrangements for the island of Taiwan remains an open question. That’s up for discussion and negotiation, no doubt.

In the past 18 months, the PRC has demonstrated a level of capability by way of naval exercises around the island. These demonstrations show at least two things:

The PRC’s navy and associated military forces have the ability to move rapidly to establish a cordon around the island, including a presence on the eastern Pacific Ocean-facing side of the island; and

The PRC has the capability to establish a protective cordon around its sovereign territory, rather than indicating any intent to military land forces on the island itself.

Rather than promote incessant talk of an impending mainland ‘invasion’ of the island, these exercises show a capacity to do something quite different. Given that one cannot ‘invade’ one’s own sovereign territory, the exercises should be interpreted as a demonstration of sovereign defensive capability. They show a capacity to restrict external forces access to the island, thereby securing Chinese sovereignty.

As for any move towards (4) Two China’s, the ROC Legislative Yuan would first need to amend the national boundaries in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution before taking the matter to a referendum. To do this, the Legislative Yuan vote has high thresholds as noted above, which in the current divided Yuan is highly unlikely to be achievable. It’s also something that’s likely to spark significant local turmoil on the island itself, as the move brings to the table the ‘moment of decision’. Given that the realisation of (4) is highly unlikely - indeed improbable to even get over the first hurdle - the best outcome for all concerned on both sides of the Taiwan Strait would be the pursuit of either (1) or (2). These options are also more suited to the interests of regional stability.

Domestic and international conditions on the island of Taiwan makes (1) the status quo an unstable and fluid situation. The US speaks of not supporting any unilateral changes to the status quo. But what the US takes the status quo to mean is increasingly at odds with how the PRC understands the status quo. For the PRC, the status quo is rather straightforward: a recognition of one China and a commitment to achieving peaceful reunification if possible. The United States actually committed to this proposition back in 1972. Recall that in the Shanghai Communique, the US committed to the following: “It reaffirms its interest in a peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question by the Chinese themselves. With this prospect in mind, it affirms the ultimate objective of the withdrawal of all US forces and military installations from Taiwan.” It would appear that it is now well and truly backtracking from this.

In recent times, it also appears that the US has been working to ‘salami slice’ not just the prospects of a peaceful settlement but also the idea of one China itself. It has been arming and training the military on Taiwan island, as if it was intent on sabotaging the prospects of a peaceful settlement.

However, stabilising a new ‘status quo’ that in effect ‘kicks the can down the road’ is a possibility.

Meanwhile, Lai Ching Te’s recent speech suggests strongly that his preference is not this, however. Rather, he has sought to ‘fly the kite’ on outcome (4), perhaps thinking that he could normalise a de facto two-nation recognition globally. Those who want to see two China’s have nowhere to hide now; Lai has brought this issue out of the shadows of ambiguity. That the question of Two China’s is in all probability likely to spark violence on the island, and perhaps even result in the resumption of an active militarised civil war across the Straits, is something those who advocate “Taiwanese sovereignty” need to come clean on. Should warfare be resumed, it is they who cannot avoid accountability.

Hic Rhodus, hic salta.

![Leader of the Republic of China Chiang Kai-shek, who was a Methodist, reads a Bible - 1940s [602x787] : r/HistoryPorn Leader of the Republic of China Chiang Kai-shek, who was a Methodist, reads a Bible - 1940s [602x787] : r/HistoryPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!O3vR!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd2bd46e2-60c1-401c-878f-80c85d01eba0_602x787.jpeg)