Hard as it try, the US can’t turn back time to an era of neocolonial economic control.

US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s recent speech, delivered on the sidelines of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank spring meetings, offers a revealing insight into the anxieties haunting US economic leadership today. Bessent’s critiques of China’s economic model and theso-called mission creep of international financial institutions are better understood as an attempt to revive an era of neocolonial economic control — one in which the United States dictates both the terms of development and the acceptable models of national success.

Bessent’s interventionism-reeking speech signals not the end of globalisation, but an ambition to reconstitute a model of globalisation in which the US occupies center stage. He speaks of China’s need to be changed, and the US’ responsibility to perform it, echoing its centuries-old ambitions to “shape and mould” developing countries such as China into an image to the US’ liking. These sentiments echo those of former White House National Security adviser Jake Sullivan.

This ambition is a reaction to unfolding realities, which in the end will also make Bessent’s ambitions an unrealisable fantasy. The rest of the world has already moved on, both in terms of the changing contours of global trade and the emergence of new institutions of payments and capital flows that decenter the US dollar. In this sense, we are witnessing not the end of globalisation, but the waning of globalisation with transatlantic characteristics.

In its place is globalisation with multipolar characteristics.

In criticising the alleged "imbalances" of China — namely, a manufacturing-heavy economy insufficiently tilted toward consumption, Bessent not only mischaracterises China’s dynamic, adaptive growth strategy, but also implicitly demands conformity to a narrow, Western ideal of economic structure. He ignores that China's manufacturing strength is underpinned by its rising household incomes and expanding domestic consumption. Far from being an uncorrected flaw, the evolution of China's economy reflects strategic prioritisation and adjustment over time, yielding stability, innovation and upward mobility for hundreds of millions.

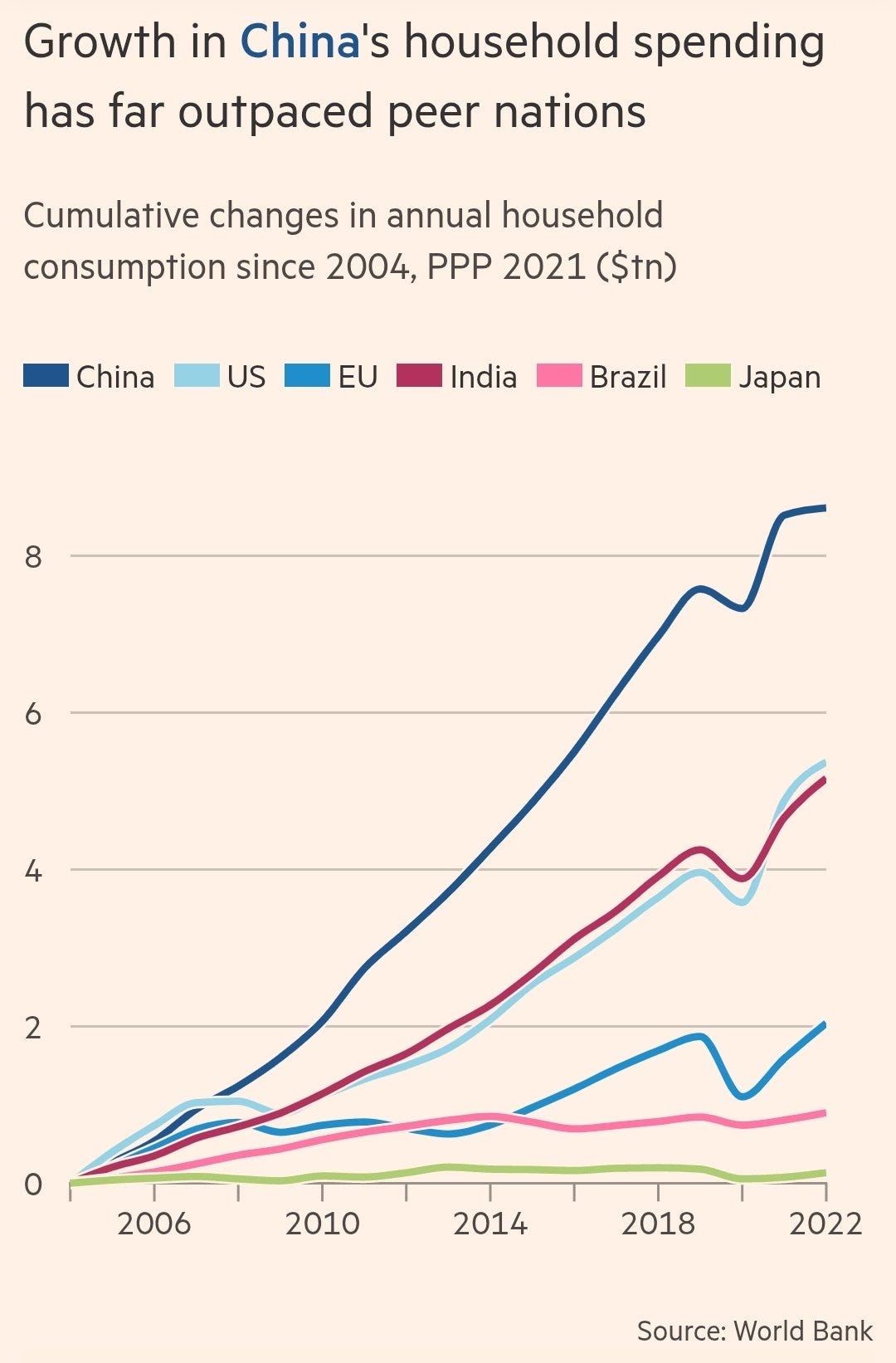

China’s household consumption levels continue to grow strongly. It has grown in absolute terms over the past 25 years, as well as in proportionate terms relative to its overall GDP. Consumption growth is underpinned by rising real incomes, which in turn are driven by ongoing public and private investment in capital formation. Even the Financial Times has acknowledge - if not truly reconciled with - this reality. See the chart below.

Rising manufacturing output has driven growth in domestic consumption, resulting in an increasing proportion of manufacturing output being consumed by the domestic economy. Today, about 80% of manufactured output in China is consumed by the domestic economy, and in some sectors - such as electric vehicles - the figure is over 90%. Bessent is simply mistaken in his core assertions.

Claims about China’s “imbalances” are the foundations of the politics of US grievance. Problems in the economic and social structure of the US are blamed on China’s model. The US’ inadequate manufacturing is due to excessive Chinese savings and suppressed consumption, rather than the US’ own priorities away from real capital formation in favour of financialisation and ballooning income inequality. Rather than confront the constraints of non-existent real wage growth for the bottom 50% of US wage earners, and the explosion of household dependence on credit cards and buy-now/pay-later schemes to put food on the table and pay rents and mortgages, the discourse of US grievance that underpins Bessent’s complaints about China relieves the US of the responsibility for its own challenges.

Bessent’s attack on the IMF and the World Bank is even more telling. His complaint about "mission creep", such as concerns with climate, gender and social issues, is a call for these institutions to abandon any pretensions of facilitating sovereign development, and to return instead to their original role as instruments of neoliberal discipline: enforcing austerity, privatization and structural dependency. In other words, Bessent wants a rollback of reforms that, however incomplete, have sought to address the failures of the Washington Consensus and the debt crises it instigated across the Global South.

Bessent’s complaints about the IMF’s "mission creep" into climate change issues also ring hollow when placed against basic facts. The US contributes nothing to the IMF’s voluntary Resilience and Sustainability Trust, which finances climate adaptation efforts for vulnerable countries. If the US government refuses to fund these initiatives, then on what grounds does Bessent object? His criticism isn’t about financial prudence or institutional focus; it’s ideological. He opposes the very idea that international financial institutions should support a broader conception of development, which addresses existential risks such as climate change that disproportionately affect and concern the countries of the Global South. The US may not view climate change as a priority; that’s its prerogative. It doesn’t contribute to the funding in any case. But these are issues that concern many others in the world. Bessent wants a world in which these concerns are ignored.

The golden thread connecting Bessent’s critiques is clear: a nostalgia for the unipolar moment when US economic ideology was global dogma. His underlying proposition is not about improving global economic governance; it is about reasserting control, so as to limit alternatives to the US-centric model, to hobble the emergence of multipolar development paths, and to preserve US preeminence at a time when it is increasingly contested.

Rather than offering a path forward, Bessent’s speech highlights the real danger: that in seeking to “fix” China and the Global South, US leadership may once again entrench a system of economic subjugation, forestalling genuine, diverse and sovereign development around the world.

Even more consequential is the accelerating pace of dedollarisation. As more countries reduce their dependence on the US dollar for trade and reserves, the foundational assumptions underpinning the IMF and the World Bank are being called into question. Bessent calls for “reform”, but his idea of reform is little more than reasserting US primacy over these institutions.

But the kind of reform that may emerge won’t necessarily be what Bessent is looking for. Today, it is not only China or a handful of rising powers that demand change. There is a broad consensus across the Global South that reform is needed, but not a restoration of post-World War II neocolonial structures. The demand is for greater representation, fairer governance and institutional autonomy.

If the US refuses to accommodate this reality, the rest of the world will not stand still. The Global South has already begun constructing parallel financial architectures, from the BRICS’ New Development Bank and other multilateral financial institutions to regional credit arrangements, that operate outside US control. Bessent’s vision of reviving US dominance through the IMF and the World Bank belongs to a bygone era. The emerging reality is a multipolar financial order, and unless the US adapts, it risks isolating itself from the future it refuses to recognize.