Defunding of USAID: A Shift in American Soft Power and Regime Change Strategies?

Even more caution is demanded as the US recalibrates

The recent decision by the second Trump Administration, via executive order, to defund the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and fold it under the administrative authority of the State Department has sent shockwaves through the U.S. domestic and international communities. This move, which includes the dismissal of tens of thousands of USAID staff globally and the reduction of its personnel to a core of fewer than 300, is an unconstitutional abuse of executive power, according to former U.S. ambassador Chas Freeman in a recent interview. The legal concerns have also been articulated in this article, published in ProPublica.

If these are domestic concerns, it arguably marks a significant shift in how the United States projects its influence abroad.

But does it?

While some have celebrated this decision as a blow to the so-called ‘deep state’ and a rejection of ideological or “WOKE” biases, others view it as leading down the slippery slope towards domestic authoritarianism. Still others argue that it is a dangerous retreat from America's role as a promoter of liberal international values, undermining genuine development assistance along the way. However, a closer examination suggests that the defunding of the USAID is less about ending American meddling in other countries and more about reshaping the tools of American power to align with the Trump Administration's vision of “national interest.” It also speaks to the fundamental failure of the USAID as a “moral salve” in the context of post World War 2 global development, opening up new avenues for countries to demand fairer economic development that does not compromise, but rather, empowers national sovereignty.

The History and Role of USAID

Established in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy, the USAID was created to consolidate various foreign assistance programs under a single agency. Its stated mission was to promote economic development, improve public health, and support democratic governance in developing countries. Over the decades, the USAID has channeled billions of dollars in aid to countries around the world, often positioning itself as a benevolent force for good. However, critics have long argued that the USAID’s activities are deeply intertwined with American geopolitical interests, serving as a tool for advancing U.S. hegemony under the guise of humanitarianism.

The USAID’s funding has been substantial. Between 1961 and 2020, the agency disbursed over $500 billion in aid, making it one of the largest aid organisations in the world. Its 2023 budget was in the order of US$43.8 billion. This funding has supported a wide range of activities, from infrastructure projects and disaster relief to media networks and civil society organisations. While many of these initiatives may have had some positive impacts, others have been criticised for promoting American interests at the expense of local autonomy. More recently, funding to assorted initiatives associated with so-called diversity (DEI) and sexuality identity politics have been the focus of criticism, though in the schema of the USAID’s total funding these assorted activities are largely niche in nature.

More broadly, the USAID has been accused of funding media outlets that propagate pro-American narratives and of supporting NGOs that destabilise governments deemed hostile to U.S. interests. The revelations emerging as a result of the defunding of the USAID shows just how extensive its funding of media networks around the world has been.

Shaping Narratives and Funding Media Organisations

The USAID has long been involved in funding media networks and organisations around the world, ostensibly to promote democracy, freedom of the press, and development. For example:

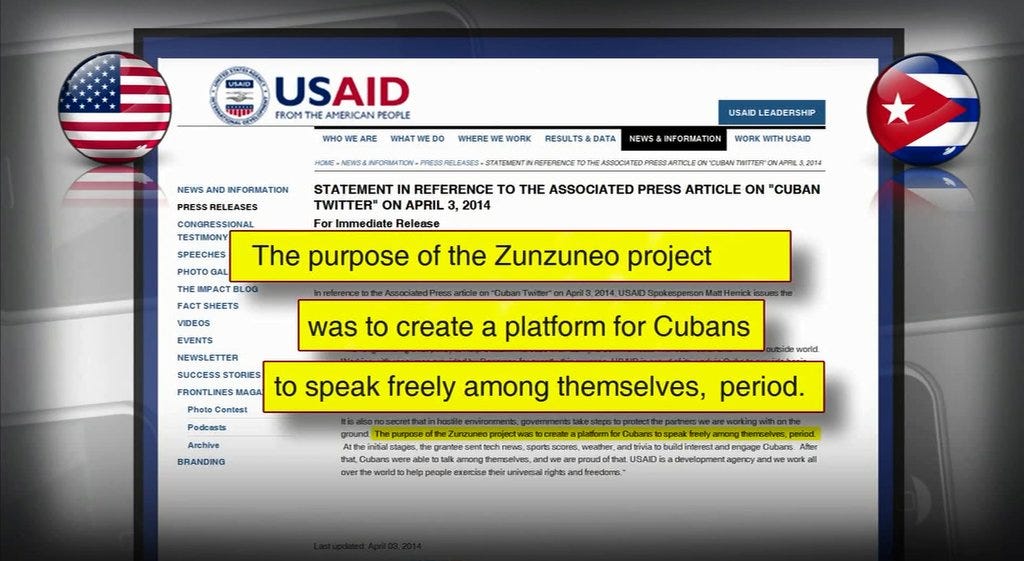

Cuba: Promoting Regime Change Through Media. The USAID has been deeply involved in efforts to undermine the Cuban government, particularly through media and information campaigns. One of the most controversial examples is the creation of Zunzuneo, a Twitter-like social media platform launched in 2010. Funded by the USAID and developed by Creative Associates International, a Washington-based contractor, Zunzuneo was designed to create a network of Cuban users who could be mobilised for political purposes. The platform was secretly operated by the USAID, and its true purpose was hidden from users, who were unaware that their data was being collected and analysed to identify potential dissidents. The program was part of a broader effort to destabilise the Cuban government by fostering dissent and organising opposition. When the program was exposed by the Associated Press in 2014, it sparked international outrage and accusations that the USAID was engaging in covert regime change operations under the guise of development aid.

Venezuela: Funding Opposition Media. In Venezuela, the USAID has funded media outlets and organisations that are critical of the government, particularly under the leadership of Hugo Cháves and Nicolás Maduro. For example, the USAID has provided financial support to Canal de Noticias NTN24, a Colombian-based news channel that has been accused of promoting anti-government narratives in Venezuela. The channel has been a vocal critic of the Maduro government and has provided extensive coverage of opposition protests, often framing them in a positive light. The USAID has also funded NGOs and civil society organisations in Venezuela that produce and distribute anti-government content. These efforts have been part of a broader U.S. strategy to undermine the Maduro government and support opposition forces. Critics argue that such activities amount to interference in Venezuela's internal affairs and contribute to political instability.

Ukraine: Supporting Pro-Western Narratives. In Ukraine, the USAID has played a significant role in supporting media outlets that promote pro-Western narratives and counter Russian influence. Following the 2014 Euromaidan protests and the ousting of President Viktor Yanukovych, the USAID ramped up its support for independent media in Ukraine. This included funding for Hromadske TV, an online television station that has been critical of both the Yanukovych government and Russian-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine. The USAID has also funded training programs for Ukrainian journalists, aimed at promoting ‘objective’ and ‘independent’ reporting. However, critics argue that these programs often emphasise narratives that align with U.S. interests, such as support for NATO integration and opposition to Russian influence. By bolstering pro-Western media, the USAID has contributed to the polarisation of Ukrainian society and the escalation of tensions with Russia.

Bolivia: Media Campaigns Against Evo Morales. In Bolivia, the USAID has funded media organisations and NGOs that have been critical of the government of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first Indigenous president. For example, the USAID provided financial support to Fundación UNIR Bolivia, an organisation that produces media content aimed at promoting dialogue and reconciliation. However, critics argue that the organisation’s work has often been used to undermine the Morales government by highlighting its shortcomings and amplifying opposition voices. The USAID has also funded training programs for Bolivian journalists, ostensibly to promote freedom of the press. However, these programs have been accused of encouraging reporting that aligns with U.S. interests, such as criticism of Morales’ socialist policies and his alignment with leftist governments in Latin America. These efforts have been seen as part of a broader U.S. strategy to counter the influence of leftist movements in the region. Morales expelled the USAID from Bolivia in 2013.

Middle East: Promoting Pro-American Narratives. In the Middle East, the USAID has funded media projects aimed at promoting pro-American narratives and countering anti-U.S. sentiment. For example, in Iraq, the USAID provided funding for Al-Hurra, a U.S.-government-funded satellite television channel that broadcasts in Arabic. While Al-Hurra claims to provide objective news coverage, critics argue that it serves as a propaganda tool for promoting U.S. interests in the region. Similarly, in Afghanistan, the USAID has funded media outlets and training programs for journalists as part of its efforts to promote democracy and counter extremism. However, these efforts have often been criticised for prioritising narratives that align with U.S. military and political objectives, such as support for the U.S.-backed government and opposition to the Taliban.

Latin America: Funding Anti-Leftist Media. Throughout Latin America, the USAID has funded media outlets and organisations that oppose leftist governments and movements. For example, in Nicaragua, the USAID has provided financial support to Confidencial, an independent media outlet that has been highly critical of the government of Daniel Ortega. Similarly, in Ecuador, the USAID has funded media organisations that have opposed the government of Rafael Correa, a leftist leader who has been a vocal critic of U.S. intervention in the region. These efforts have been part of a broader U.S. strategy to counter the influence of leftist governments in Latin America, which have often sought to challenge U.S. dominance in the region. By funding media outlets that promote anti-leftist narratives, the USAID has contributed to the destabilisation of targeted governments and the polarisation of political discourse.

Eastern Europe: Countering Russian Influence. In Eastern Europe, the USAID has funded media projects aimed at countering Russian influence and promoting pro-Western narratives. For example, in Georgia, the USAID has provided financial support to Rustavi 2, a television station that has been critical of the government's pro-Russian policies and has advocated for closer ties with the West. Similarly, in Moldova, the USAID has funded media outlets that promote European integration and oppose Russian-backed separatists in the breakaway region of Transnistria. These efforts have been part of a broader U.S. strategy to counter Russian influence in the region and promote the expansion of NATO and the European Union. By funding media outlets that align with these objectives, the USAID has played a key role in shaping public opinion and political outcomes in Eastern Europe.

Similarly in Asia, the USAID has played an active role in promoting American geopolitical interests and narratives through funding support of various local media and civil society-cum-political organisations. For example:

In Myanmar, the USAID has long provided funding for so-called pro-democracy groups, civil society organisations, and media outlets opposing the incumbent government. This includes support for groups linked to Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD). After the 2021 military coup, the USAID increased funding to opposition groups, including the National Unity Government, an exiled government-in-waiting formed by ousted officials. The USAID has also provided funding to independent media outlets that oppose the military junta, leading critics to argue that it is actively supporting resistance movements. Some view these efforts as part of a broader U.S. strategy to counter China’s influence in Myanmar, particularly regarding Chinese-backed infrastructure projects.

In Cambodia, the USAID has provided funding to opposition parties, civil society groups, and independent media, particularly those critical of Prime Minister Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party. The Cambodian government has accused the USAID and affiliated NGOs of interfering in domestic politics, notably through support for the Cambodia National Rescue Party, which was dissolved by court order in 2017. Hun Sen’s government has expelled and restricted USAID-backed organisations, accusing them of attempting to foster a “colour revolution” akin to those seen in Eastern Europe.

In Thailand, the USAID has supported so-called pro-democracy groups, particularly during the periods of military rule. The Thai government has accused some U.S.-funded NGOs of supporting opposition protests, particularly during the student-led demonstrations against the monarchy and military-backed government in 2020–2021.The USAID’s programs in Thailand also extend to countering Chinese influence in areas like media and technology, with some funding directed toward independent journalists and civil society actors.

While the USAID was not officially acknowledged as being a direct player in the protects in Hong Kong (the 2014 so-called Umbrella Movement and the riots that broke out during 2019-2020), various U.S. government-linked organisations, including USAID-funded entities, have been accused of providing support to activists and opposition groups in Hong Kong. The USAID has provided funding to the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), a U.S. Government regime change agitation and orchestration organisation active across the globe. The NED, in turn, has funded various groups and media outlets in Hong Kong including:

Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor (HKHRM)

Civic Party, and

Apple Daily and other self-claimed ‘independent’ media.

The NED’s financial reports confirm that it provided millions in funding to Hong Kong civil society organisations leading up to and during the 2010s protests. Furthermore, some Hong Kong protest leaders, including Joshua Wong and members of Demosisto, have attended events hosted by U.S.-based organisations linked to USAID-funded initiatives. The Oslo Freedom Forum, which has received USAID and NED support, provided platforms for Hong Kong activists to coordinate strategies with other global opposition movements. Some reports suggest that U.S. diplomats and NGO representatives held meetings with protest leaders, raising concerns about foreign involvement in the movement.

Debased Development Assistance

The post-WWII economic order was fundamentally designed to serve the interests of the United States and its Western allies. The IMF and the World Bank, both dominated by Western powers, imposed conditions on loans and assistance that often prioritised the repayment of debts and the integration of developing economies into the global capitalist system over their long-term development needs. This approach, known as the "Washington Consensus," emphasised privatisation, deregulation, and trade liberalisation, often at the expense of local industries and social welfare programs.

For many developing nations, the result was not development but dependency. Structural adjustment programs (SAPs) imposed by the IMF and the World Bank forced countries to cut public spending, devalue their currencies, and open their markets to foreign competition. These policies often led to economic stagnation, increased inequality, and social unrest. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, SAPs contributed to the collapse of local industries and the erosion of public services, leaving many countries worse off than they had been before.

In this context, the USAID emerged as a way for the United States to address the symptoms of underdevelopment without challenging the underlying structures that perpetuated it. By providing aid for specific projects—such as infrastructure, education, and health—USAID could claim to be promoting development while avoiding any fundamental reform of the global economic system.

The USAID’s role as a “moral salve” is evident in its dual mandate of promoting development and advancing U.S. foreign policy interests. On the one hand, the agency has funded projects that have had tangible benefits for recipient countries, such as the eradication of smallpox and the construction of schools and hospitals. On the other hand, its activities have often been tied to broader geopolitical goals, such as countering Soviet influence during the Cold War or promoting neoliberal economic policies in the post-Cold War era.

This duality has limited the USAID’s effectiveness as a development agency. By prioritising short-term political objectives over long-term development goals, the USAID has often undermined its own efforts. For example, during the Cold War, the agency funded authoritarian regimes in Latin America and Southeast Asia that were aligned with U.S. interests but opposed to democratic governance and social justice amongst groups deemed to be hostile to the U.S.. Similarly, in the post-9/11 era, the USAID’s “democracy promotion” programs in the Middle East have been criticised for prioritising regime change over genuine political reform. Hypocrisy was the order of the day.

Moreover, the USAID’s reliance on U.S. contractors and consultants has often resulted in aid that is more beneficial to American companies than to recipient countries. This "tied aid" model has been criticised for perpetuating dependency and undermining local capacity-building. In many cases, USAID-funded projects have failed to achieve their stated objectives, leaving recipient countries with little to show for the billions of dollars spent.

The failure of the USAID to address the structural barriers to development reflects the broader failure of the post-WWII economic order. The IMF and the World Bank, far from promoting development, have often acted as enforcers of a global economic system that prioritises the interests of wealthy nations over those of the Global South. By imposing conditions that undermine local industries and social welfare programs, these institutions have denied developing nations the policy space they need to pursue autonomous development strategies.

For example, the IMF’s insistence on fiscal austerity has often forced developing countries to cut public spending on education, health, and infrastructure, undermining their long-term development prospects. Similarly, the World Bank’s focus on large-scale infrastructure projects has often benefited foreign corporations and local elites at the expense of ordinary citizens. In many cases, these projects have led to environmental degradation, displacement, and social unrest. The result is a global economic system that perpetuates inequality and dependency. While the United States and other wealthy nations have prospered, many developing nations have been trapped in a cycle of poverty and underdevelopment. The USAID, as a product of this system, has been unable to address these structural barriers, serving instead as a band-aid solution that allows the United States to claim it is promoting development without addressing the root causes of underdevelopment.

USAID and Regime Change: The U.S. as a “Rogue State”

One of the most controversial aspects of the USAID’s work has been its involvement in regime change operations. While the agency officially denies any role in such activities, evidence suggests that it has often worked in tandem with other U.S. government entities, such as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the NED, to undermine foreign governments. For instance, USAID-funded programs have been linked to the so-called “colour revolutions” in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, as well as to efforts to destabilise governments in Latin America and the Middle East.

Below are examples of the USAID's direct and indirect involvement in regime change campaigns:

Chile (1970–1973) – Overthrow of Salvador Allende. The USAID played a role in efforts to undermine socialist President Salvador Allende before his ousting in a U.S.-backed coup. The agency funnelled money into opposition parties, business groups, and media campaigns to erode Allende’s support. It worked closely with the CIA, which led a broader destabilisation campaign against Allende’s government.

Nicaragua (1980s–1990) – Opposition to Sandinistas. The USAID funded opposition groups and anti-Sandinista media during the U.S. campaign against the leftist Sandinista government. It provided financial assistance to groups aligned with the Contras, a U.S.-backed rebel group fighting the Nicaraguan government. The USAID’s aid was channeled through programs promoting “democratic governance,” though much of it went to opposition figures.

Venezuela (2000s–Present) – Opposition to Hugo Cháves & Nicolás Maduro. The USAID, through its Office of Transition Initiatives (OTI), has funded opposition parties, student movements, and media organisations. It has worked through NGOs such as Súmate, an opposition electoral group linked to efforts to remove Cháves through a recall referendum. Under Maduro, the USAID has continued funding opposition groups and provided direct financial and logistical support to figures seeking to overthrow his government.

Bolivia (2000s–2013) – Attempts to Undermine Evo Morales. The USAID supported opposition groups, particularly in separatist movements in Santa Crus, where there were efforts to break away from Morales’ socialist government. In 2013, Morales expelled the USAID from Bolivia, accusing it of funding groups that sought to destabilise his government.

Iraq (2003) – Reconstruction & U.S. Control Post-Saddam. After the U.S. invasion, the USAID managed extensive reconstruction projects but also played a role in political engineering. It helped shape Iraq’s new governance structure, funding U.S.-friendly political factions and civil society groups aligned with American interests.

Libya (2011–Present) – Support for Anti-Gaddafi Forces. During the NATO-backed intervention in Libya, the USAID provided financial support to civil society groups opposing Muammar Gaddafi. Following his overthrow, the USAID played a role in shaping Libya’s political transition, supporting factions favourable to Western interests.

Syria (2011–Present) – Funding Opposition & Rebel Groups. The USAID provided extensive funding for Syrian opposition groups under the banner of humanitarian assistance and governance support. Some of this funding allegedly ended up supporting groups linked to anti-Assad militias, including organisations affiliated with the Free Syrian Army (FSA).

Egypt (2011–2013) – Role in Arab Spring & Muslim Brotherhood Ouster. The USAID supported democracy promotion programs during the Arab Spring, helping opposition activists use digital tools and organising strategies. Under Mohamed Morsi’s presidency, the USAID was accused of backing groups working to remove him, aligning with the 2013 military coup led by General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.

Ukraine (2014) – Maidan Uprising & Regime Change. The USAID funded opposition media, civil society organisations, and activists involved in the 2014 Euromaidan protests, which led to the overthrow of President Viktor Yanukovych. It worked alongside the NED to train and support anti-government groups. Leaked phone calls (notably the Victoria Nuland recording) revealed U.S. officials discussing how to shape Ukraine’s post-Maidan government.

Georgia (2003) – Rose Revolution. The USAID provided funding and logistical support to opposition groups that overthrew President Eduard Shevardnadze. It backed NGOs like the Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, which played a significant role in mobilising the public. In recent months, efforts were again launched by anti-government forces in an effort to delegitimise the government and destabilise the political situation in Georgia. To date, these efforts have failed.

Belarus (2000s–Present) – Opposition Support. The USAID has consistently funded opposition media and NGOs in Belarus, aiming to weaken President Alexander Lukashenko’s rule. The agency’s funding has supported dissident groups and protest movements.

Sudan (2000s–2019) – Ouster of Omar al-Bashir. The USAID-backed civil society organisations and opposition groups in Sudan long before al-Bashir’s removal in 2019. It played a role in promoting opposition-aligned governance reforms.

Zimbabwe (2000s–Present) – Opposition to Mugabe & ZANU-PF. The USAID funded opposition parties and civil society groups opposed to Robert Mugabe’s rule. The Zimbabwean government repeatedly accused the USAID and NED of attempting to engineer regime change.

The involvement of the USAID in regime change operations is part of a broader pattern of American interventionism that has been extensively documented by scholars and journalists. In his book Killing Hope: U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II, William Blum catalogues over 50 instances of U.S.-backed regime change, from the overthrow of Iran's Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953 to the ousting of Haiti's President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 2004. Similarly, Stephen Kinser's Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq highlights how the U.S. has repeatedly used military force, covert operations, and economic pressure to install puppet regimes that serve its interests.

The Defunding of USAID: A New Chapter in American Foreign Policy?

The decision to defund the USAID and place it under the direct control of the State Department has been framed by the Trump Administration as a cost-cutting measure and a way to align foreign aid more closely with American national interests. However, the move also reflects President Trump’s personal grievances with the agency. Trump has accused USAID-funded organisations of attacking him and his family, particularly in relation to the Hunter Biden laptop affair, which he claims was covered up by mainstream media outlets supported by the USAID.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio has echoed these sentiments, arguing that the USAID has been “misaligned” with American foreign policy priorities. Rubio has suggested that the agency will be reformed to better serve the Trump Administration’s vision of U.S. national interest, which appears to prioritise unilateralism and transactional diplomacy over multilateralism and humanitarianism. While Rubio has not explicitly endorsed regime change operations, his rhetoric suggests that the Trump Administration is not opposed to using American power to shape political outcomes abroad.

The restructuring of the USAID raises important questions about the future of American soft power. On the one hand, the defunding of the agency could be seen as a retreat from America's role - during the Unipolar period in particular - as a promoter of so-called liberal international values. On the other hand, it could represent an attempt to streamline and centralise the tools of American influence, making them more effective and responsive to the Trump Administration's priorities.

While the defunding of the USAID may signal a shift in how the U.S. projects its power, it does not necessarily mean an end to American meddling in other countries. The Trump Administration has already shown a willingness to use both hard and soft power to pursue its goals. Moreover, the U.S. has a long history of using non-state actors, such as private military contractors and NGOs, to advance its interests abroad. Private military contractors look like increasing their presence in the Middle East, is a recent case in point.

The Trump Administration’s ambitions to “own” Gaza or annex territories like Canada, Greenland, or the Panama Canal suggest that regime change and destabilisation will remain key components of American foreign policy. Trump’s refusal to rule out the use of force in some of these endeavours further raises concerns about destabilisation risks emanating from Washington itself. In the case of China, the U.S. is likely to continue its efforts to counter and where possible destabilise the country and its regional periphery through covert operations and propaganda campaigns, even if it does so through channels other than the USAID.

Against this historical context, during the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit in 2022, China’s President Xi Jinping warned that one of the biggest security threats facing Eurasia and SCO members was the risk of “colour revolutions” — that is, externally orchestrated or foreign-backed uprisings aimed at regime change. Xi emphasised that external forces were attempting to destabilise SCO member states through political manipulation, subversion, and support for opposition movements. He called for unity among SCO nations to resist foreign influence that could trigger unrest. Xi directly linked “colour revolutions” to Western-backed efforts to interfere in the internal affairs of sovereign nations. He urged SCO members to strengthen security cooperation, particularly against cyber threats, political subversion, and external ideological influence.

In light of the revelations of the USAID funding involvements in narrative formation and support of political interference operations in assorted countries over decades on most continents, the risks identified by President Xi are particularly prescient.

Conclusion

The defunding of the USAID represents a significant moment in the evolution of American foreign policy. While some have celebrated the move as a rejection of the “deep state” and ideological biases, others have warned that it could undermine America's ability to promote democracy and human rights abroad. A closer examination suggests that the Trump Administration’s decision is perhaps less about ending American meddling and more about reshaping the tools of American power to align with its vision of national interest. Pursuing personal vendettas is another aspect of the defunding of the USAID.

As the U.S. continues to grapple with its role in a changing, increasingly multipolar world, the defunding of the USAID serves as a reminder that American foreign policy has always been driven by particular conceptualisations of American self-interest - whether that be as the unbridled leader of the liberal world order or as the narrowly cast prosecutor of “America First” policies. While the methods and institutions may change, the underlying goal of maintaining and expanding American authority remains the same. In this sense, the defunding of the USAID is not the end of America's meddling ways, but rather the beginning of a new chapter in the long and often controversial history of U.S. interventionism.

Rather than rejoicing at the defunding of the USAID, countries around the world are likely to intensify their vigilance about foreign interference. If the USAID is to mutate and be absorbed into the broader apparatuses of state, then greater attention will be required to be directed toward the role of NGOs and think tanks as critical nodes for funding and organisation aimed at advancing American interests through the destabilisation of others.