This essay continues a series of explorations of the dynamics impacting the war in Ukraine and its possible settlement. It explores three things: (1) what I call the Trump Apologia, which seeks to blame-shift the debacle as Trump seeks a fast track solution; (2) Russia’s longstanding views on European security; and (3) Wang Yi’s recent speeches on multipolarity. Taken together, the argument is that whatever the peace settlement in Ukraine, it is ultimately tied to the contest between America’s version of a post-unipolar world and the kind of multipolarity that both Russia and China have advocated.

The US-Russia meeting in Riyadh, set against the backdrop of the Vance-Hegseth double-act at the Munich Security Conference, has given rise to a flurry of frisson and rising transatlantic tensions. For some there’s a frisson of excitement, that the first meeting between the Americans and Russians portend a rapid resolution of the Ukraine war; for others it is filled with dread that the comforts of an American security blanket over Europe are increasingly in tatters.

In much of the commentary occasioned by, and surrounding these recent events, there appear to be at the same time a series of elisions. They are:

An emerging suspension of critical perspective amidst a growing Trump Apologia. No doubt, disdain of Biden, Von der Leyen and the others who’ve personified the incessant warmongering, as flag-bearers of neocon / neoliberal / globalist ambitions, provoke such reactions. Anything but these ‘villains’ is a breath of fresh air, particularly if there is hope that peace may come at last. But these visceral instincts have seeped into a fawning acceptance of Trump’s own hyperbolic claims, as well as those of his associates.

A failure to take Russia’s longstanding positions on European security and Ukraine’s role in it seriously. No doubt, as well, a yearning for an end to the bloodshed drives hopes of a rapid-fire settlement. The Riyadh meeting is then interpreted in this affective frame, with many expecting some kind of ‘grand bargain’ to be struck between the US and Russia. Rather than take Russia's long-held and consistently articulated perspectives seriously, the question of a Ukrainian peace is reduced to being a mere extension of the terms initialed at Istanbul in late March 2022.

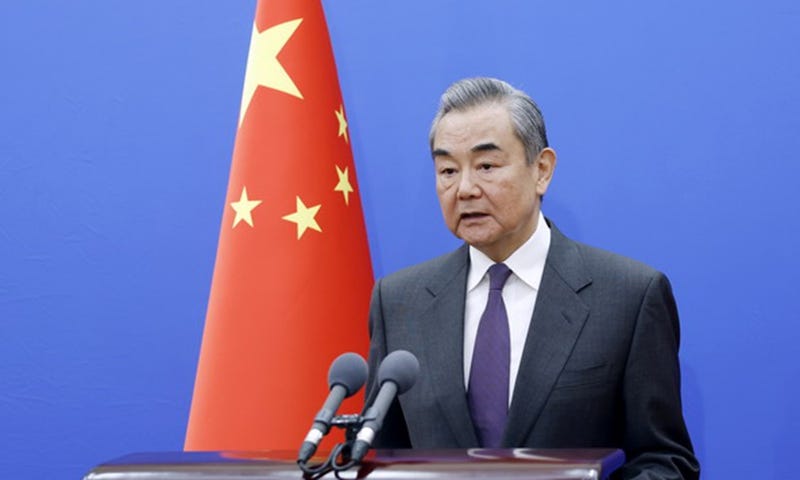

Amidst the headline grabbing of Vance and Hegseth, much of the global media attention - in the mainstream media at the very least - has failed to pick up on the speech delivered by China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the Munich Security Conference, and the subsequent remarks he delivered at the United Nations and the meeting of G20 Ministers in South Africa. Wang’s remarks about multipolarity jar against the perspectives so far articulated by the Americans - including Rubio’s now well-known interview with Megyn Kelly in which he acknowledged the end of unipolarity - and when coupled with Russia’s positions in security architecture paint a different picture as to what is at stake in resolving the Ukraine war.

The likely resolution of the war in Ukraine is difficult to conceive without appreciating the criticality of these latter two areas. Any Ukrainian peace settlement is likely to be intertwined with the unfolding contest over multipolarity.

Trump Apologia

Donald Trump has fashioned himself as the ‘peace president’, seeking to sheet home the blame for the war in Ukraine to his predecessor, Joe Biden. Trump’s rhetorical habit is to assert that the war would not have happened had he been president. Of course, this is an unfalsifiable counterfactual, and must be taken as a matter of blind faith. You either believe Trump or you don’t.

But that misses the point. It obfuscates Trump’s role during his first term as President in laying the groundwork for the war, and cultivates a collective amnesia around the willingness of the Republicans in Congress during Biden’s term in office to wave through funding appropriations and military commitments to Ukraine. In this period, Trump did not demur on the substance of the commitments. Repetition of the assertion that the war would not have started had he been president does not absolve Trump from his own responsibility during the period from 2016 through to the present day.

The rhetorical aim now is to blame-shift through a combination of character assassination and historical obfuscation. As Trump seeks to extricate the US from the war, he needs to minimise the risk that responsibility for the strategic defeat in Ukraine will be levelled at the United States, and more particularly at him personally. What we have witnessed since the Munich Security Conference and events since is an increasingly aggressive campaign by the Americans to apportion blame and frame the post-war narrative. The strategic defeat resulted despite American support, due to European ‘free loading’ and Ukrainian theft, corruption and incompetence, so the arguments go.

It’s little wonder the Europeans and the UK are apoplectic. As for Zelensky, he now knows what it feels like to be a proxy whose used-by date has come.

The Build-Up

Between 2016 and 2020, the United States provided substantial financial and military assistance to Ukraine as part of efforts to strengthen its defense capabilities following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. During this period, the U.S. provided approximately $1.95 billion in security assistance to Ukraine. This assistance was aimed at bolstering Ukraine's military capabilities, supporting defense reforms, and improving interoperability with NATO forces. In 2018, the U.S. approved the first-ever delivery of Javelin anti-tank missiles to Ukraine, a clear heightening of military assistance (worth approximately $47 million). Equipment such as counter-artillery radars, night vision devices, medical supplies, secure communications systems, and vehicles were also provided. The U.S. provided ongoing training for Ukrainian forces through the Joint Multinational Training Group-Ukraine (JMTG-U) at the Yavoriv training center in western Ukraine.

With US support, the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) became Europe’s largest land army, trained to NATO standards and supplied with a growing amount of NATO / US equipment. Between 2015 and the end of 2021, the AFU underwent significant expansion and modernisation, becoming Europe’s largest land army outside of Russia.

In 2015, the AFU comprised approximately 250,000 personnel, including all branches, with about 150,000 active troops, and about 80,000 mostly untrained reservists. At the time, combat-ready troops were limited. The AFU mainly operated Soviet-era equipment, with shortages of modern armour, artillery, and air defense. By 2021, however, the AFU had grown to over 400,000 total (including all branches), with about 250,000 active troops. It had an estimated 900,000 trained reservists due to expanded training programs, and over 100,000 part-time fighters as part of the Territorial Defense Forces formed and expanded in 2021. Large segments of the army had completed NATO-interoperable training with over 10,000 Ukrainian personnel receiving NATO-standard training each year, primarily in the UK, Poland and Germany. As for equipment, by 2021 there was heavy integration of NATO-supplied gear (e.g., Javelins, modern artillery), coupled with the provision of modernised armour, improved drone capabilities, and stronger air defences. In doctrine terms, the AFU began to shift from purely Soviet doctrine to Western operational tactics.

By the end of 2021, Ukraine had Europe’s largest non-Russian standing land force, fully prepared for large-scale conflict. The Trump Administration played its role in this process.

As an aside, it’s worth noting that Trump did not lift the sanctions imposed on Russia by Obama nor did he move to bring Russia back into the G8. On this score, Trump represented continuity.

Ukrainian Agency in the context of Proxy Grooming

In recent days, Trump has attacked Ukraine and more specifically Zelensky for his failure to negotiate peace on multiple occasions. Trump references the Minsk Agreements, executed in 2015, and the failure to see through the Istanbul Accord of late March 2022, as cases in point. In doing so, Trump effectively diminishes the status of Ukraine as a proxy and elevates Ukrainian “agency” by arguing that it had plenty of opportunities to “not” start the war or to “negotiate” a peace.

Ukraine has been in large part a proxy of NATO ambitions in eastern Europe. It has done as the US and NATO have wanted it to throughout the period after the Maidan coup. The failure to realise the Minsk agreements is a case example of Ukraine being led up the Primrose Path, as John Mearsheimer famously put it. Much of this failure can and should be sheeted home to the western powers that continued to ply Ukraine with military equipment and training in readiness for war. The Istanbul Accord, initialed by the Russian and Ukrainian negotiators in late March 2022, failed due to American and UK interference. The western forces promised Ukraine that they would supply Ukraine with whatever was needed, for as long as it took, to defeat Russia. Ukraine was promised that the west would mount a sanctions war against Russia that would bring Russia to its knees within weeks or months. Ukraine went along with this, believing that they would not only defeat the Russians but also regain Crimea in the process.

To now imply that Ukraine was ‘free’ to negotiate a peace deal with Russia, and failure to do so was a function of Ukrainian incompetence, refuses to acknowledge the role of the western powers in grooming Ukraine throughout the period since 2008, when George Bush Junior promised Ukraine and Georgia membership of NATO.

Buyer’s Regret

The last element of the Trump Apologia goes to how Trump’s moves to secure Ukrainian ‘rare earths’ for the US are being explained.

In early February 2025, President Trump proposed that Ukraine supply the U.S. with rare earth minerals and provide the US with various commercial rights to these resources (and others, including gas and “anything else”) as a form of repayment for the financial assistance provided during the war. Zelensky has so far resisted American demands on this front. Zelensky has countered with demands for security guarantees and expressed concerns about the valuation and terms of such a deal.

Today’s discussions are somewhat different to how the topic was first canvassed in September 2024. At the time, during a meeting with Trump, Zelensky suggested that Ukraine's critical resources could be utilized to strengthen economic ties and ensure sustained military assistance from the United States. This proposal was intended to create a mutually beneficial partnership, focusing on future collaboration rather than repayment for past aid.

Senator Lindsey Graham, a vocal advocate for supporting Ukraine, highlighted the strategic importance of Ukraine's mineral resources. He noted that Ukraine possesses significant reserves of lithium, titanium, and other rare earth elements essential to the American economy. Graham argued that a partnership in this sector would reduce U.S. dependence on adversarial nations for critical minerals and provide a compelling reason for continued American support. Graham further emphasized that Ukraine's mineral wealth could transform the U.S.-Ukraine relationship, making it more advantageous for the United States. He stated, "President Trump can go to the American people and say Ukraine is not a burden, it's a benefit. They're sitting on top of trillions of dollars worth of minerals that all of us can benefit from by aligning with the West."

These discussions in 2024 centered on establishing a strategic partnership that would utilize Ukraine's mineral resources to offset future military commitments and reconstruction efforts, rather than addressing debts from previous aid.

It seems that Trump has since parlayed this to being a means of recovering monies spent to date, in a case of “buyers regret”. In recent developments, Trump has shifted his stance regarding Ukraine's rare earth resources. In a marked shift from the focus of discussions in 2024, Trump has since proposed that Ukraine provide the United States with $500 billion worth of rare earth resources as compensation for past military aid. Interestingly, an estimated 70% of the financial components of military aid from the US was spent in the US, with defence contractors, so the US economy has already received a significant boost as a result.

Trump is particularly miffed that European financial assistance to Ukraine was provided by way of loans, whereas American support was not. Trump is insistent on “getting our money back”, in a clear move that aims to re-write - well after the event, and in light of the west’s strategic defeat in Ukraine - the terms of provisioning in the first place. The Trump Apologia has failed to acknowledge this shift in relation to the mineral resources as a form of payment for future security guarantees (which is what it was initially) to a form of repayment for monies already provided. Some estimates suggest that the terms proposed by the Americans are more severe than those imposed on Germany at Versailles after World War 1.

Eurasian Security

If the Trump Apologia is largely about absolving the US from responsibility for the strategic defeat, all of this effort fails to recognise the reality of Russia’s own positions in relation to Eurasian security.

Trump no doubt wants to bring the Ukraine conflict - or at the very least, America’s exposure to it - to a rapid conclusion. He wants to wash his hands of the mess, while ensuring he isn’t blamed for it. The longer the negotiations drag on, the more likely he begins to co-own defeat. Trump knows the U.S. and the west has lost, so cutting the losses is the best move. His issue is to make sure he doesn’t inadvertently co-own the debacle. This is especially the case when he wants to:

Husband resources to tackle China;

Rebuild the U.S. to try to reclaim primacy; and

Keep the Europeans under the U.S. thumb but have them pay more for protection.

Russia, on the other hand, has no need to work to Trump’s timetable.

The war in Ukraine, from Russia’s point of view, is aimed at bringing to an end a longstanding conflict. This conflict is the legacy of an unresolved western European security architecture that would adequately take into account Russia’s own security interests. The concerns of Russia aren’t new, and should be well known to most keen observers. Unsurprisingly, Russia made clear that it is intent on addressing and resolving the “root causes” of the conflict, not just dealing with its epiphenomenal symptoms.

We can understand Russia’s position by reflecting on a number of key speeches or documents.

The 2007 Munich Security Conference speech delivered by Russia President Vladimir Putin, criticised the expansion of NATO. He argued that “it represents a serious provocation that reduces the level of mutual trust.” This was a prescient warning. He went on to criticise the destabilising effects of efforts to transform the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe “into a vulgar instrument designed to promote the foreign policy interests of one or a group of countries.” These observations about the OSCE predate the recent revelations about the mis-use of USAID funding in the name of development assistance, and provide salutary insights into the historic behaviour of western state apparatuses in other countries. With the benefit of history, Putin’s 2007 speech can be seen as a clear warning that continued eastward expansion of NATO would end in tears.

The draft Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation, was presented on December 17, 2021 (together with the associated draft agreement with NATO - see below), as tensions in Ukraine began to reach a potential breaking point. Of course, in between Putin’s 2007 speech and the timing of this draft Treaty, many words have been published from the Russian side on concerns about Russian security, the eastward expansion of NATO and Russia’s staunch opposition to Ukraine becoming a NATO member. Indeed, the Minsk agreements were negotiated in early 2015, which contained a package of measures, ratified by the United Nations Security Council, were designed to de-escalate tensions and bring some form of peaceful accord to the Ukraine situation. There have been arguments as to who was responsible for the breakdown of the Minsk agreements, which need not detain us here, though it is worth noting that Francois Hollande (then President of France) and Angela Merkel (then Vice Chancellor of Germany) - both present at the signing of the Minsk agreements - have admitted that the agreements were only to “buy time” and enable Ukraine to build up its army. As we saw earlier, this build-up was aided and abetted by substantial American and European contributions. These admissions from Hollande and Merkel are meaningful, because they affirmed Russian suspicions of western sincerity.

The draft Agreement on Measures to ensure the security of The Russian Federation and member States of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization was presented to NATO. Notice that this Agreement was presented at the same time as the draft treaty with the US. This indicates that from the Russian perspective, a sustainable or durable resolution of the security crisis could only be achieved with agreements between Russia and both the transatlantic bodies. An agreement with one but not the other was unlikely to deliver a durable outcome.

Vladimir Putin’s speech at the meeting with senior staff of the Russian Foreign Ministry, delivered on June 14, 2024, spoke of the emerging multipolar order in which new institutions - such as BRICS - would play prominent roles in facilitating multilateral governance amongst nations. In that speech, Putin lamented the lost opportunity presented at the end of the Cold War to “build a reliable and just security order.” He believed that this “did not require much – simply the ability to listen to the opinions of all interested parties and a mutual willingness to take those opinions into account.” Alas, for Putin, “a different approach prevailed. The Western powers, led by the United States, believed that they had won the Cold War and had the right to determine how the world should be organised. The practical manifestation of this outlook was the project of unlimited expansion of the North Atlantic bloc in space and time, despite the existence of alternative ideas for ensuring security in Europe.”

Such alternative ideas took concrete form in the draft agreement with NATO and Treaty with the US, presented in late 2021. These two documents represent the first time a formalized instrument has been proposed by the Russians to give effect to these other ideas, to give ventilation to the broader notion of indivisible security, drawn from the non-binding Helsinki Accord of 1975.

The draft treaty included eight articles. The first of which laid the foundation stone, binding the parties to “cooperate on the basis of principles of indivisible, equal and undiminished security.” It went on to say that neither party shall use the territories of other nations to prepare or carry out “an armed attack against the other Party or other actions affecting core security interests of the other Party.” Critically, it specifically bound the US to “undertake to prevent further eastward expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and deny accession to the Alliance to the States of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.” At the time, the US ignored the proposed draft and refused to engage with the Russians at all on the draft’s contents.

The partner document, the agreement with NATO, had nine articles. The first mirrored the draft treaty, committing the signatories to have their relations guided “by the principles of cooperation, equal and indivisible security. They shall not strengthen their security individually, within international organizations, military alliances or coalitions at the expense of the security of other Parties.” The agreement went on, among other things to commit to the following:

“The Russian Federation and all the Parties that were member States of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization as of 27 May 1997, respectively, shall not deploy military forces and weaponry on the territory of any of the other States in Europe in addition to the forces stationed on that territory as of 27 May 1997” (Article 4). … and

“All member States of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization commit themselves to refrain from any further enlargement of NATO, including the accession of Ukraine as well as other States.” (Article 6)

NATO also ignored the draft agreement. As they say, the rest is history. Within about 10 weeks of these documents being submitted to the US and NATO respectively, the Ukrainian bombing of the Donbas intensified and on February 24, 2024 Russia began the Special Military Operation (SMO).

Russia has, for a long time, advocated a post-Cold War security architecture that was premised on the notion of indivisible security. The SMO was initiated in part as a consequence of the failure of such a security architecture to take shape in Europe, and for Russia’s long-held security concerns to be adequately addressed by the western powers. Since 2007, from the perspective of Russia, it has had to endure much hardship and intensified threats to its existential security. It has also committed considerable effort and resources to establish institutions and practices, and participate in them, which it believed better reflected its own approach and preferences when it came to a feasible post-Cold War global security order. Putin’s references to the role of BRICS in his 2024 speech is an example of this, not to mention the ongoing efforts Russia undertakes to nurture and sustain its diplomatic relationships across the non-western world.

In this climate, and after fighting a 3 year war against a US / NATO resourced and trained Ukrainian army to secure the upper hand on the battlefield, Russia is now in a position to advance its own ideas of an adequate and durable security resolution. That it was the Americans that initiated talks is testament to the reality that Russia has achieved a significant strategic victory on the fields of Ukraine. Russia can continue the war of attrition, and is able to do so until a settlement is realised. It has made it clear that it will not countenance a ‘cease fire’, but is interested in securing a meaningful and durable peace.

This is a peace that can only be achieved in the context of multipolarity and the realisation of the notion of indivisible security.

Multipolarity versus Great Power Rivalry

China has been a long-term advocate of a multipolar global security architecture. Its position can be traced to the principles of peaceful coexistence it first articulated 81 years ago, and to China’s own commitment to the principles that continue to animate the non-aligned movement some 80 years after the Bandung Conference.

China’s approach to multipolarity can be gleaned from its Global Civilisation Initiative, Global Security Initiative and Global Development Initiative, which together form a coherent articulation of a world view premised also on the notion of indivisible security and shared interests of all countries. The conceptual framework articulated in these documents has recently taken concrete form in three speeches delivered by China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

At the Munich Security Conference, Wang delivered a succinct statement of China’s approach to multipolarity. He followed this up with remarks at the United Nations on the occasion of China assuming the rotating chair. Lastly, he spoke at the G20 meeting of ministers in South Africa, where again he articulated China’s vision for global security through a multipolar lens.

These are important speeches, which unfortunately have not been properly covered by the western mainstream media which has otherwise been distracted by the hubbub caused by JD Vance’s full-front critique of the European Union and Pete Hegseth’s various remarks making it clear that the Europeans should not count on the US as a low-cost backstop.

Wang’s remarks on these various occasions paint a picture of multipolarity in which no country, regardless of size, should be treated differently from the others. Equal treatment of all countries is grounded on adherence to the provision of international law. A multipolar world requires standards for all. Wang went on to emphasise the centrality of the practice of multilateralism, which is anchored in extensive consultation and joint contribution for shared benefit. Major countries should play the role of enabler, rather than spoiler or expropriator.

They are significant for at least three reasons.

Firstly, they demonstrate that China has a clear view as to what it means by a multipolar world. Multipolarity could, in theory, lay the groundwork for chaos and uncertainty as the stability that comes with a dominant hegemon gives way. Effective governance institutions and practices are critical to mitigating the risk of chaos and instability, and existing institutions such as the United Nations are pivotal to this effort. No doubt, Wang is not naive as to the challenges and limitations of bodies like the United Nations, but is at the same time clear that since its foundation, the United Nations has also been a bulwark against unremitting chaos globally. China’s approach to multipolarity is premised on the idea that all countries have equal footing; that is, no one country gets to decide who can and who cannot eat from the table, or determine who is on the menu.

Secondly, China’s approach is consistent with the overall tenor and contours of Russia’s own approaches. Unsurprisingly, both Russia and China have aligned their own security postures on the Eurasian continent around institutions like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and the nations’ respective leaders have also agreed on the wider notion of a ‘Eurasian Security Club’.

Thirdly, China’s vision of a post-unipolar world contrasts with that articulated by US Secretary of State Marco Rubio. In a recent interview, in widely published remarks, Rubio conceded the end of American unipolarity. Less remarked upon were observations in that same interview that America’s focus would increasingly be trained on China as a threat. He argues that China “wants to be the most powerful country in the world and they want to do so at our expense”. This focus on China as an adversary is a consistent theme across Trump’s new administration, including the Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth who’s made it clear where his priorities are. The recognition of multipolarity came with it a very particular sense of the state of international relations today, which can be characterised as a return to ‘great power rivalry’ and geographic spheres of influence.

For Rubio, the demise of unipolarity heralds a period of great power rivalry where diplomacy is the key to mitigating risks of differences descending into conflict. Each major power has its sphere of influence, though it is also clear from comments of others in the Trump administration that the U.S. considers the western Pacific to be part of America’s sphere of influence. Wang’s version of multipolarity rejects this notion. For Wang, there can be no ‘great powers’ that demand or receive different treatment than that expected by all countries. The U.S. has previously proposed a “G2”, involving a bilateral concert between China and America, but China rejected such a proposition.

Divergent Ambitions

Trump’s desire to extricate the U.S. from Ukraine is tied up with his administration’s objective to concentrate efforts and resources on the containment of China. Just as Trump is mindful that any delays in drawing a line under America’s exposure to the quagmire of Ukraine runs the risk of seeing him held responsible for the strategic defeat, he is no doubt of the view that the sooner the U.S. can train its sights on China the better. This line of reasoning has been long articulated by one of the newly appointed assistant secretaries of defence, Elbridge Colby.

As for Russia, it has sacrificed much to be in the position it is today. It has long held views about what a durable and satisfactory security architecture for Western Europe should be. It now sees the opportunity to bring their ideas to the table and ultimately see them implemented. It’s already 18 years since Putin warned of the catastrophe in waiting should the west press forward with NATO expansion; Russia can wait a little longer to solve the “root causes”.

Russia undoubtedly is aware of Trump’s time pressures and can exploit those to its advantage. No matter the narrative manoeuvres associated with the assorted Trump Apologia, the underlying weakness of the western and U.S. military position amplifies the leverage Russia possesses. That Trump has also made a brazen grab for Ukrainian natural resources assets in a fit of ‘buyer’s regret’ tells the world a lot about the present state of mind of America’s executive leadership. Russia has yet to seriously test the Americans in either diplomatic or military terms, as they re-engage after a 3 year hiatus.

In parallel, since Putin’s 2007 address, China has risen as a major power. Like Russia, it has navigated an extended period of American unipolar hegemony, in which the U.S. has exerted considerable military and economic pressure upon it. The US continues to do so. Against this backdrop China’s economy has expanded to a point where it is now larger than that of the United States, on purchasing power parity terms. It is the largest trading partner of over 140 nations. Militarily, its modernisation now puts it in a position where the U.S. is no longer in a position to intimidate China in its own region.

At the same time, a new ethos of multipolarity has matured over 80 years. China, Russia and other states have worked tirelessly to consolidate multipolar institutions - like BRICS - to ensure the voices of the global south can be better represented. The individual and collective robustness of BRICS nations’ economies means they’ve reached a point where they can stare down American threats of tariffs and sanctions. Indeed, it is clear that deepening intra-network collaboration in trade, investment, technology exchange and payments systems can only strengthen BRICS nations in their pursuit of their own national economic development.

The fate of the peace settlement in relation to the war in Ukraine is intimately and inextricably tied to the unfolding contest between America’s ‘great power rivalry’ version of multipolarity, and the vision of ‘indivisible security’ that has been articulated in their own ways by Russia and China. The treaty and agreement drafts laid out by Russia in December 2017 point to the kind of arrangements Russia is looking to achieve. Meanwhile, in its aim to free up resources to focus on China, the US runs the risk of being seen to again ‘cut and run’ before throwing erstwhile allies under the proverbial bus. As American efforts to blame others intensifies, those being cast aside may well reflect on alternative possibilities that depend less on the benevolence of an American hegemon, and more on the security that can be achieved through the creation of a mutually reinforcing fabric of indivisible security.