A Rising South

Shifting tectonic plates as multipolarity takes shape - reflections on G20 in the context of BRICS and ASEAN summits

This is a briefing note I prepared a little over 12 months ago, in September 2023, as a reflection on the spate of global meetings - the G20 in India, the BRICS in South Africa and ASEAN Summits. The note predates the outbreak of the latest year of conflict in Gaza and Lebanon, so that didn’t feature at all in the discussions. The 2024 program of major global meetings is almost complete now, with the G20 to convene in Brazil on 18-19 November. The text below is ‘as is’, and is published as something of an historical reflection (written at the time) as well as by means of perhaps setting the stage for a similar reflection on this year’s summitry. I hope readers find it interesting and useful.

Introduction

The wheels of global change continue to grind away.

As we enter the middle of September 2023, we have been witness to 3 big global confabs, with the most recent in the trifecta being the just concluded G20 in New Delhi, India. Before that, Johannesburg hosted BRICS with over 50 observer nation delegates in attendance; and Jakarta played host to the 47th ASEAN leaders summit.

So, with a bit of water now under the bridge, what can we make of this recent flurry of “summitry”?

The short story is this: global multipolarity continues to take shape. The G20 was a capstone on first BRICS and subsequently ASEAN. US-led transatlantic dominion ebbs, but is not yet a spent force.

Let’s work our way through this via the G20.

Shifting sands

Part 1: Ukraine or India? That is the question

The ‘big question’ in the lead-up to the summit was what was going to happen insofar as the leaders’ communique or declaration was concerned when it came to the question of Russia and Ukraine. Failure to achieve a consensus declaration was pitched as a would-be failure and an embarrassment to the host country. The collective West was outmanoeuvred in relation to the Ukraine question. For the past 18 months the collective West, without fail, has made condemnation of Russia and declaration of support for Ukraine a totemic issue.

India’s consistent refusal to play along - going so far as to ignore sanctions and profit from buying Russian crude oil low, processing it and on-selling to European customers high - has put the Western powers in a bind. With China’s shadow looming large over the transatlantic political elite, and those of the US’ Asian subimperial subordinates, the West could not afford to rub India up the wrong way.

As Western powers feted India and its PM Modi, they shelved their pretences on questions of ‘human rights’, long held up as the West’s signature ‘moral differentia specifica’. Not only was criticism of India’s refusal to abide by anti-Russia sanctions muted (Josep Borrell threatened action once, but that went nowhere), the West’s elite have been uncharacteristically silent when it came to (1) the growing spate of religious persecution and violence in India against Muslims and Christians in particular; (2) the reality that India is home to the most slaves in the world, with estimates ranging from a low of 8 million to a high of 16 million; (3) the plight of child labourers who are found in all sorts of industries; (4) the increasing repression of media inquiry and public dissent; and (5) the persistence of lawful matrimonial rape.

In any other national case, under any other circumstance, the howls of opprobrium and the chorus of condemnation from the West would have been deafening. Sanctions of one sort or another would simply have been de rigeur.

But no, India is safe. For now. The West needs it as a bulwark against the so-called ‘China threat’. A faux bonhomie is rolled out, with all the accoutrement of official visits and receptions. India’s own political elite are nothing if not astute and cunning. They successfully exploited the West’s desperation and weakness. The West could ill-afford to cause embarrassment by holding out on a ‘consensus declaration’.

Without the distraction of the ‘big personalities’ of Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin, Modi had clear air. You’d almost be tempted to wonder whether this was orchestrated.

In any case, the western powers acquiesced. India made the most out of the hand it had been dealt by circumstance. The West’s unilateral authority was demonstrably diminished.

The focus of the declaration, insofar as the conflict involving Russia and Ukraine (and NATO) is concerned, was on the human costs of war, the deplorable possibilities of ‘going nuclear’ and the need to uphold the UN charter in its entirety. Modi has always insisted that his primary concern was humanitarian tragedy. Modi and India consistently refused to condemn Russia.

Ukraine was unceremoniously thrown under the bus as brute RealPolitik saw the West calculate that India’s favour was more important. We know that India’s diplomatic work in the ‘hours before midnight’ was aided by a coordinated effort from other global south diplomats. For the global south, the bigger picture was front and centre. This was an opportunity to shift the ground, and consolidate the outcomes of BRICS and ASEAN, in which new loci of global authority and influence emerged and consolidated.

Ukraine was angry at what it saw as a watered down declaration. American neocons were similarly aghast. Indeed, some - like former White House National Security Advisor John Bolton, a hawk, in the West concluded in a Washington Post opinion piece that the G20 might as well “abolish itself”, and others like Derek Grossman from the neocon RAND Corporation at once complemented the New Delhi declaration as a “truly remarkable feat” while deriding India for taking “the lowest common denominator approach of not even mentioning ‘Russia’” (Exhibit 1). In any case, Ukraine currently has nowhere else to go; wasn’t invited despite trying to get a seat at the table (India said no, and the West could do nothing about it); and is staring down the reality of desolation at the end of the Primrose Path.

Exhibit 1

On the singularly pivotal question of Ukraine, the geopolitics was a West in retreat. Russia was cock-a-hoop (Exhibit 2); the global south gained succour from a successful push-back against the West and levered open the door just that little further for a future multipolar world.

The tilt of global geopolitics towards a new multipolarity took another small step forward.

Exhibit 2

Part 2: the BRI alternative

Adjacent to the G20 proper, the U.S. - together with India, Saudi Arabia, and the European Union - announced an agreement amongst the parties to develop a land-sea transport corridor linking the Indian Ocean with Greece (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3

This high-cost project, estimated at some $17-20 billion - involving transport infrastructure together with parallel energy pipelines and data cables - would involve developing a rail link from Dubai, through Saudi Arabia and Jordan (curiously, not party to the memorandum of understanding), to one or both of the Haifa Ports in Israel. From there cargo would be shipped to the Piraeus Port in Greece, then transferred to road transport to the rest of Western Europe.

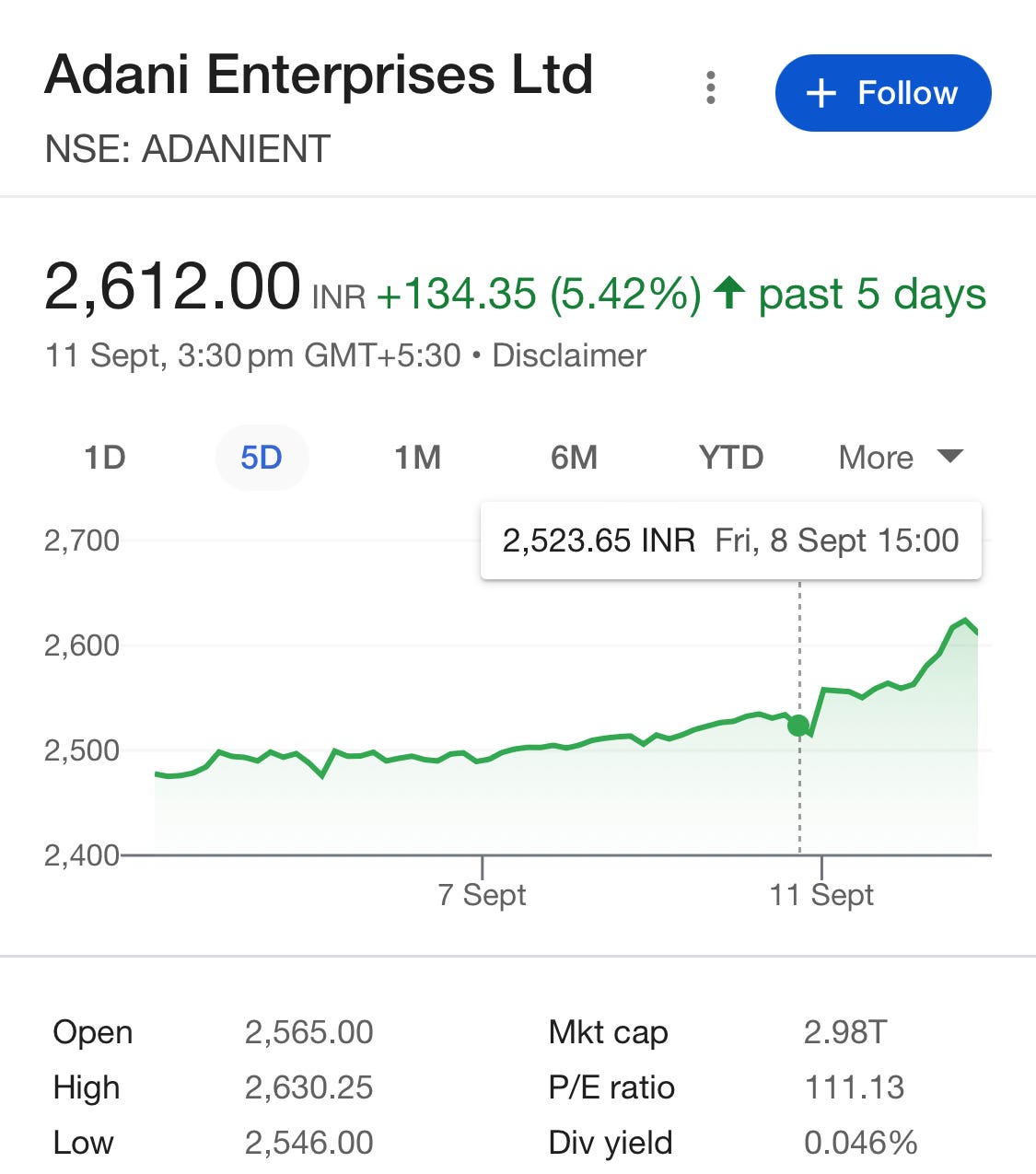

This project has been billed as an alternative to the BRI. In terms of scale, the two aren’t even comparable. At the beginning of its second decade, the BRI has been involved in projects with a little over $1 trillion of capital investment. In pure numbers terms, the India-Middle East Corridor (IMEC) is no BRI alternative. Further, key elements of the proposed corridor already involve Chinese participants - in particular, the Saudi Arabia land-bridge project, one of the Haifa ports and the Piraeus Port. The other (old) Haifa Port was recently acquired by Indian oligarch Gautam Adani - a close associate of Modi’s - for $1.2 billion, so it’s entirely conceivable that the aim is to funnel container traffic through Adani’s port to underpin further capitalisation. This model - of state sponsorship of Adani, amongst other Indian oligarchs - is a tried and tested feature of crony capitalism under the Modi government. Given this ‘crony’ flavour, it’s not surprising that some Indian commentators, such as Arun Kumar, a retired Professor of Economics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, have been extremely critical of the IMEC.

Meanwhile, the Chinese built and operated new Haifa Port has the latest technologies enabling high volume super efficient handling of containers. Should the Adani owned older port want to compete it will need considerable upgrades and / subsidies. From Modi’s point of view, the clear hope is that others will help share the capital cost burden of upgrading his friend Gautam Adani’s recent acquisition. The share price of Adani jumped on the back of the announcement (Exhibit 4), before falling again a couple of days later.

Exhibit 4

As things stand, if the project is feasible and gets funding (the US contribution needs Congressional approval, which is anything but certain; and there’s much hope on private leveraged finance), and gets off the ground, it’s likely to take up to 2 decades to come to fruition (without working with the existing Chinese developed and operated infrastructure) and would, in any case, be a boost to the BRI network rather than an alternative to it. The Chinese operators of the Piraeus Port in Greece would no doubt welcome the additional containerised traffic.

As for its significance, according to the European Commission, “India is the EU’s 10th largest trading partner, accounting for 2.1% of EU total trade in goods in 2021, well behind China (16.2%), the USA (14.7%) or the UK (10%)”. Whether 2.1% of EU trade in goods is sufficient to justify the investment and the risk, only time will tell.

There’s another interesting dimension to India’s westward transport connectivity strategic ambitions, which again the collective west would rather stay mum about. And that’s the International North South Transport Corridor, which India, Iran and Russia have been working on for the best part of the last twenty years. The corridor is up and running, but inconveniently runs through Iran and Russia.

In effect the Saudi line bisects the INSTC and the currently dominant sea route via the Suez Canal (the red and blue lines respectively below - Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5

Rather than being an alternative to the BRI, The IMEC is a possible complement which further consolidates a multipolar world over a unipolar one. The more options available the less likely any single power can sanction others unilaterally.

With all that said, there are plenty of reasons why the proposed corridor may simply die a slow death before it ever sees the light of day. Studies will be needed; funding will have to be committed; risks must be carried. Let’s not forget, this supposed BRI alternative is the third announced by the transatlantic powers in the past 3 years.

Economic Lens

The G20 was formed to deal with the need for multinational macroeconomic coordination in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Its mandate has principally been about economic challenges. In the leadup to the summit, issues of global development and finance were identified as critical matters for consideration by the New Delhi G20. The declaration certainly identified and reiterated the need for reform of relevant institutions, but was ultimately big on motherhood statements and light on detail. Again, it came under heavy criticism from the likes of Kumar who excoriated the declaration as whitewashing domestic and global problems, and reinforcing the uneven power balances that exist.

The declaration also acknowledged the global challenges of uneven development and the need for better coordination of macro economic policy. That said, little concrete detail was advanced. The same goes for trade. While raising the importance of a stable, rules-based trade regime with the “WTO at its core”, it does not appear that any concrete action was achieved in relation to the most obvious impediment to the functioning of the WTO, namely America’s ongoing refusal to appoint a judge to the WTO’s Appellate body.

The declaration is largely a string of motherhood statements with little that’s concrete. That’s possibly the nature of these things. That of course leaves it open to criticism. While I too am tempted to be somewhat critical of its ‘lack of teeth’, I do think that it does represent a subtle, but certainly not necessarily a permanent, shift in the balance of power … the door is now open for Brazil to take up the cudgel and transform ‘intent’ into meaningful institutional change. The declaration, especially paragraph 21 on financial inclusion, speaks of “the continuous development and responsible use of technological innovations including innovative payment systems, to achieve financial inclusion of the last mile and progress towards reducing the cost of remittances”, dovetails or aligns quite nicely with the concrete work that the BRICS is now undertaking on international financial systems and payments processes, under the chairmanship of Russia in 2024. That a former Brazilian president now heads BRICS’ New Development Bank suggests that the pieces are well lined up for some substantial progress in 2024 on global financial institutional reform.

The declaration also speak of the need for an enhanced role of Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), in what an only be interpreted as a not-too-subtle critique of the prevailing dominant institutions of global development finance - namely, the IMF and the World Bank, institutions that are dominated by the transatlantic powers.

Global Governance

The declaration was implicitly critical of the evolved state of global governance institutions today, in effect acknowledging that the United Nations - in practice - has failed to live up to its original promise. The declaration observed that, “The need for revitalised multilateralism to adequately address contemporary global challenges of the 21st Century, and to make global governance more representative, effective, transparent and accountable, has been voiced at multiple fora. In this context, a more inclusive and reinvigorated multilateralism and reform aimed at implementing the 2030 agenda is essential.” In effect, the consensus was that the prevailing world order was insufficiently representatively, ineffective, opaque and unaccountable; and that multilateralism must be reinvigorated.

In the context of the G20 coming on the back of BRICS and ASEAN - two institutional bastions of multipolar voices - the declaration’s admonition of the state of global governance was a slap in the face to the so-called ‘rules based international order’. Was it a mere slap with a ‘wet lettuce leaf’? The answer to that question lies not with the G21 as it will become, but with the ongoing work of BRICS and ASEAN, and other associated institutions.

A similar critical tone can be detected in the passages dealing with global financial institution reform. The declaration (paragraph 48) declared, “We underscore the need for enhancing representation and voice of developing countries in decision-making in global international economic and financial institutions in order to deliver more effective, credible, accountable and legitimate institutions.” There would be no need for this conclusion and call if the dominant institutions of global development finance were sufficiently representative in which the voices of developing nations were well heard. Again, this is a not-too-subtle acknowledgement that developing countries have been left out of the key decision-making institutions and processes of global finance, to their detriment. That said, if one was looking for concrete action on debt relief, reform of global debt provisioning and coordinated action on addressing the deleterious impacts on borrower nations as a result of US monetary policy, there was little to be found in the declaration. On this score, the US didn’t come away entirely empty-handed.

Conclusions

The evolution of the global order of things is, today, subject to intense scrutiny and ‘round the clock commentary. Unfortunately, much of this is mired in the ‘gotcha’ and ‘scorecard’ mentality that seems to dominate the contemporary media landscape. The 24/7 news cycle, together with the plethora of never-ending social media, creates an environment in which the ebb and flow of global affairs and the shifts in geopolitical tectonic plates are reduced to ‘sporting match analogies’. Things are, however, never quite so ‘black and white’.

Host countries of major global leadership events are also under the spotlight. The fact is, South Africa, Indonesia and India all successfully discharged their custodial duties in hosting their respective gatherings of national leaders and their delegations; well done. Custom also seems to dictate that host nations are given some latitude to claim a disproportionate amount of attention and favour. India, in particular, made the most of the opportunity to pursue a range of national interests while at the same time - in concert with the other nations of the global south - secured consensus recognition that the prevailing ‘international rules based order’ was inadequate and unacceptable. The admission of the African Union as the 21st member of the grouping symbolically captured the spirit of the times, and hopefully points to a stronger voice for the developing world.

That a clearly fractious world was becalmed for a couple of days in New Delhi is no mean feat. Kudos to India and its leaders and diplomats for these small mercies. Meanwhile, even if one can be disappointed at the shortage of concrete action, the G20 has held the door ajar for the ongoing development of multipolarity, the challenges of which can now be taken up, in earnest, by the nations of the BRICS+, ASEAN and Brazil in its capacity of G21 chair.

The global sands have shifted.